Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 2

A short note on how and why I share book links

Have you ever watched a flame flicker and felt, for a moment, as though it were thinking?

As though the darkness around it wasn’t an absence, but a presence—waiting, listening, opening a door ?

Tonight’s reading lives exactly in that space : the space where shadows breathe and thought becomes its own form of alchemy.

We begin our exploration of Belgian literature with the greats—because that is, in truth, the order in which my own reading pile revealed itself to me. And today, I wanted to honour one of the most extraordinary figures to emerge from Belgium: Marguerite Yourcenar, born in Brussels, later a naturalised citizen of both France and the United States, and the first woman ever admitted to the French Academy.

Yourcenar’s life reads like a novel before she ever wrote one. Born to a bourgeois father of French Flemish descent and a mother from the Belgian nobility who died just ten days after her birth, Marguerite spent her childhood in her grandmother’s home, surrounded by adults, languages, books, and a father who taught her ancient Greek as casually as one teaches a child to tie their shoes. She never went to school. She learned Latin and Italian on her own. And she learned the world by following her father on business trips, absorbing the human theatre around her with the quiet, incisive attention that would one day shape her prose.

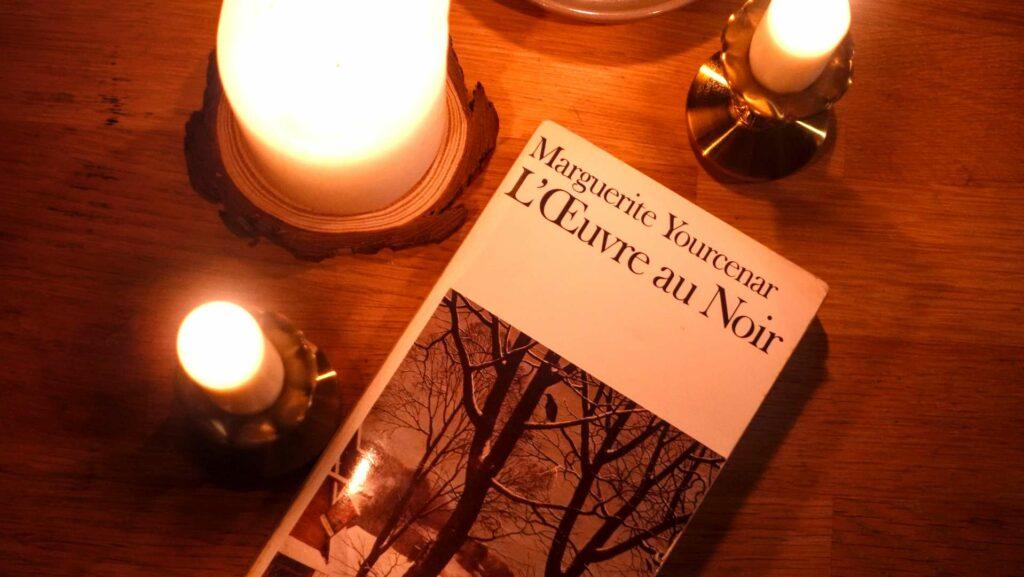

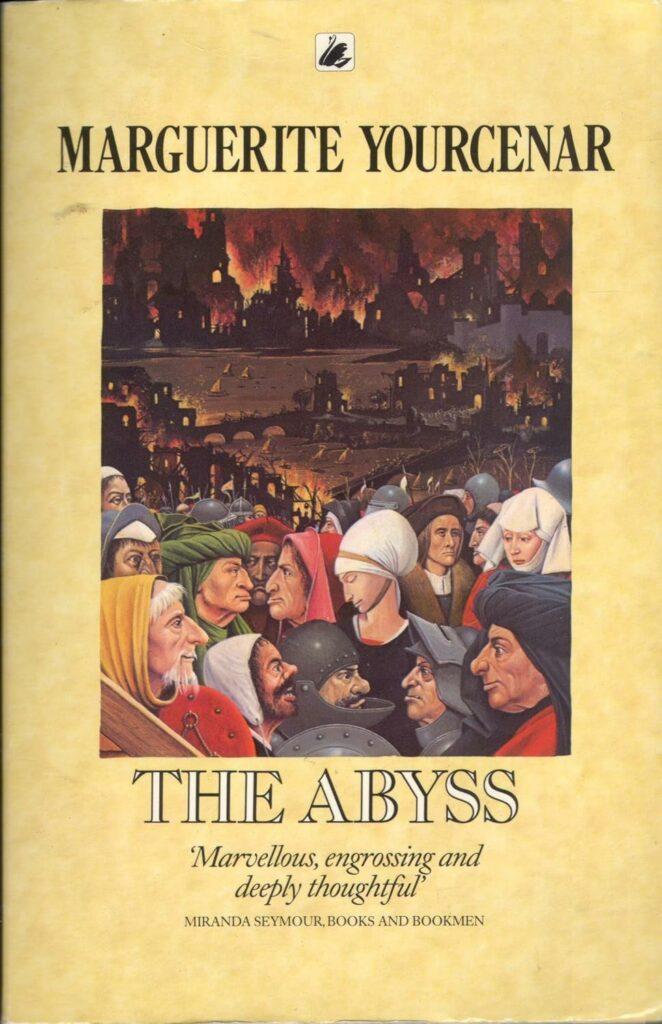

You feel all of this—this unusual education, this solitude, this precocious intimacy with ideas—when you begin reading her. For our entry point, I chose her second-most famous novel, one that feels deeply anchored in the Belgian spirit: L’Oeuvre au Noir, translated into English as The Abyss.

At its heart, the novel follows Zénon, a physician, philosopher, alchemist, and restless seeker living in 16th-century Europe—a man perpetually on the edge of danger because he refuses to submit his mind to the comforts of dogma. Part fugitive, part visionary, part scholar, he moves through a world torn by religious wars, political suspicion, and the great intellectual anxieties of the Renaissance. From monastic libraries to wandering roads, from princely courts to the austere streets of Bruges, Zénon searches for truth in a time terrified of it.

What makes the novel feel almost alive is Yourcenar’s fascination with the workings of the mind—the way ideas are born, rise, clash, disintegrate. She captures the wonderment of thought itself: how the remarkable and the mundane are constructed from the same fragile scaffolding of belief. How meaning can be both profound and illusory. How tricksters sell the illusion of knowledge to princes eager to be deceived.

As she writes:

« Les notions mouraient comme les hommes : il avait vu au cours d’un demi-siècle plusieurs générations d’idées tomber en poussière. »

Ideas died like men. Over half a century, he had watched generations of notions crumble into dust.

One of the most striking scenes, for me, is Yourcenar’s fictional encounter between Zénon and Catherine de Medicis together with her astrologer Cosimo Ruggieri—a moment heavy with power, calculation, and the seductive haze of politics. I’ve always had a particular curiosity about Catherine’s deep superstition, so at odds with her image as a formidable, pragmatic ruler. And in this scene, Zénon stands there untouched—calm, lucid, entirely immune to the mirage of power that governs so many others. In a room full of dazzled eyes, he refuses the spell.

Later, on his return to Bruges, Zénon’s intellectual pursuits shift inward. For safety, he withdraws from society, and in this solitude he enters an almost metaphysical exploration of matter, thought, and self. It becomes a phase of inquiry that feels less like scholarship and more like an internal voyage—one that transcends any worldly ambition.

The original title itself, L’Oeuvre au Noir, comes from alchemy. It refers to the first and most difficult stage in the transformation of lead into gold: the breaking down, the dissolution, the necessary descent into darkness.

Yourcenar explains it beautifully:

“In alchemical treatises, the formula L’Oeuvre au Noir designates what is said to be the most difficult phase of the alchemist’s process, the separation and dissolution of substance… whether applied to matter itself, or understood to symbolize trials of the mind in discarding all forms of routine and prejudice… perhaps both at the same time.”

Some critics see the entire novel as a parallel between this dissolution of substance and the dissolution of prejudice in Zénon’s mind—an intellectual purification, painful and liberating.

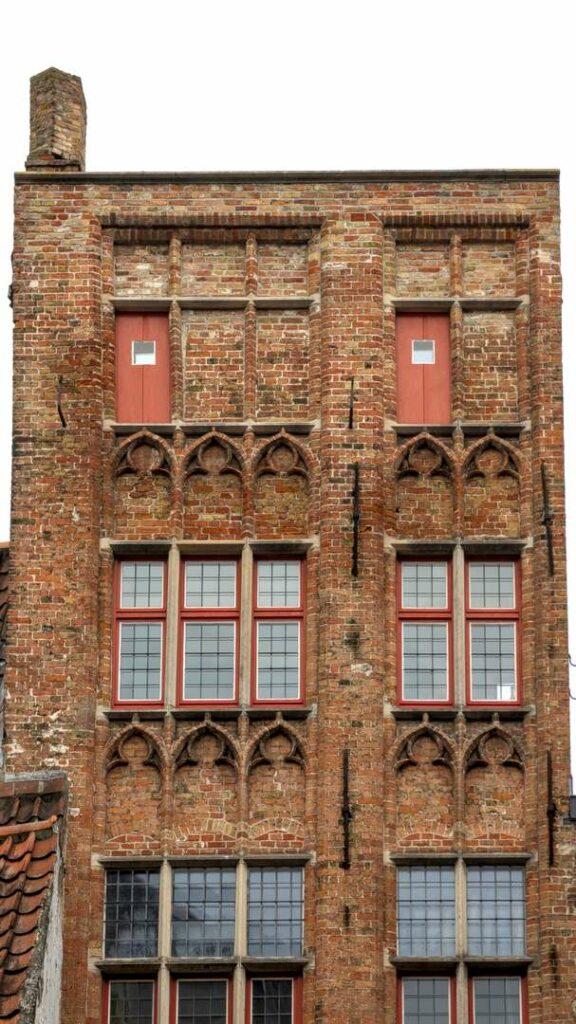

And here is something fascinating: although Zénon is undeniably a Renaissance man—curious, rational, forward-looking—the world around him still carries the shadows of the Middle Ages. The darkness lingers in the streets of Bruges, in its silent canals, in its almost austere atmosphere. And that lingering medieval shadow, contrasted with Zénon’s luminous mind, feels unmistakably Flemish. It’s a world of muted colours and meticulous detail, something out of a Bruegel painting: contemplative, earthy, threaded with a quiet mysticism.

Little did I know that this same aura of mystery and wonder was about to guide my steps into Bruges, just a few weeks after reading the novel. I had booked my accommodation back in late August—back then, Yourcenar was just a name on my list, and Zénon a total stranger to me. But perhaps they had been waiting for me all along. I checked in at De Zomere B&B and fell into conversation with Frederik, the fascinating owner of this fifteenth-century treasure, one of the oldest buildings in Bruges. One thing led to another. I mentioned my Advent Calendar, my deep dive into Belgian literature—and then he said: Do you know Marguerite Yourcenar? She was a friend of my mother’s.

I couldn’t quite believe my ears. Here I was, in a historical home in the oldest standing neighbourhood of Bruges, sleeping in what used to be the room of a poet—a friend of Marguerite Yourcenar’s, who had stayed in this same house several times while researching the material for her novel. Frederik’s generosity with stories about his family and their connection to Yourcenar became a gift I hadn’t expected. During breakfast, I read old letters that Marguerite and Katerine had exchanged over time, speaking of L’Oeuvre au Noir and how this very home could have been Zénon’s refuge in the city:

“In front of a fire just like this one, in a house just like the one you’re seeing, could very well have lived the Zénon of The Abyss.”

In all the letters I read that morning, Marguerite Yourcenar felt like the embodiment of kindness and warmth—so radically different from the world she portrayed in the novel. She felt like the candlelit world we’re stepping into tonight, giving me a new perspective on her writing.

The Abyss becomes more than a novel—it becomes a threshold. A reminder that every journey into darkness, whether alchemical or spiritual or simply human, is also a journey toward light. The kind of quiet, persistent light we seek in December, when the nights grow long and stories glow a little warmer.

It feels like the perfect beginning for our Belgian Advent Calendar, because Belgium is a land shaped by this very tension: shadow and illumination, mystery and clarity, the weight of history and the spark of imagination. In Yourcenar’s Bruges—just like in our December rooms—thought becomes its own kind of lantern.

And tomorrow, we’ll light the next one.

Day Three will take us away from the page and into one of Brussels’ royal treasures—a place where history hangs quietly on the walls, watching us back.

The clue is already hidden in today’s story.

So come back for tomorrow’s adventure.

I’ll be here, reading by candlelight, waiting.

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 2nd |

| Dear Friend, There’s a line in every letter Marguerite Yourcenar wrote to her friend, the poet Katrien Broes de Groote, that made me smile when I read them over breakfast in Bruges: “How are the two beautiful donkeys?” Without fail, between discussions of her journeys and news of mutual friends, she would ask. “Send my love to the children and a caress to the donkeys!” “Oh, how I would have loved to see your beautiful donkeys again!” Two donkeys at the family’s country estate, remembered across continents, across years, with the kind of tenderness you reserve for old friends. I asked Frederik about them, and he laughed—a warm, knowing laugh. They were real, of course. And Marguerite never forgot them. Before I read those letters, I’d placed her in my mind somewhere near Simone de Beauvoir—fierce, intellectual, armoured against sentimentality. I thought I understood her better by comparison. But sitting there in that fifteenth-century house, reading her enquiries about donkeys and her warmth toward a family she clearly loved, I realized how quick I’d been to assume. How wrong. “She was kind,” Frederik told me, “and she had a lovely sense of humour. Even as a child, I was thoroughly amused in her presence.” The woman who wrote The Abyss—that dark, uncompromising meditation on thought and persecution—was also the woman who never forgot to ask about two donkeys. It’s a reminder, I think, that we contain more than one truth. That the mind capable of tracing Zénon’s lonely brilliance was also capable of great gentleness. Tonight, when you watch the video, you’ll meet the Yourcenar I thought I knew. But I wanted you to meet this one as well—the one who loved donkeys, who made children laugh, who signed her letters with warmth. She would have liked that, I think. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.