Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 10

A short note on how and why I share book links

Do you remember when you learned how to look at art? Who was your first guide? And what marked your imagination in front of a painting or a sculpture? Was it a parent pointing out the play of light in a Vermeer, a teacher explaining the anguish in a Munch? For most of us, our first encounter with art comes mediated through someone else’s eyes, someone who taught us not just what to see, but how to see.

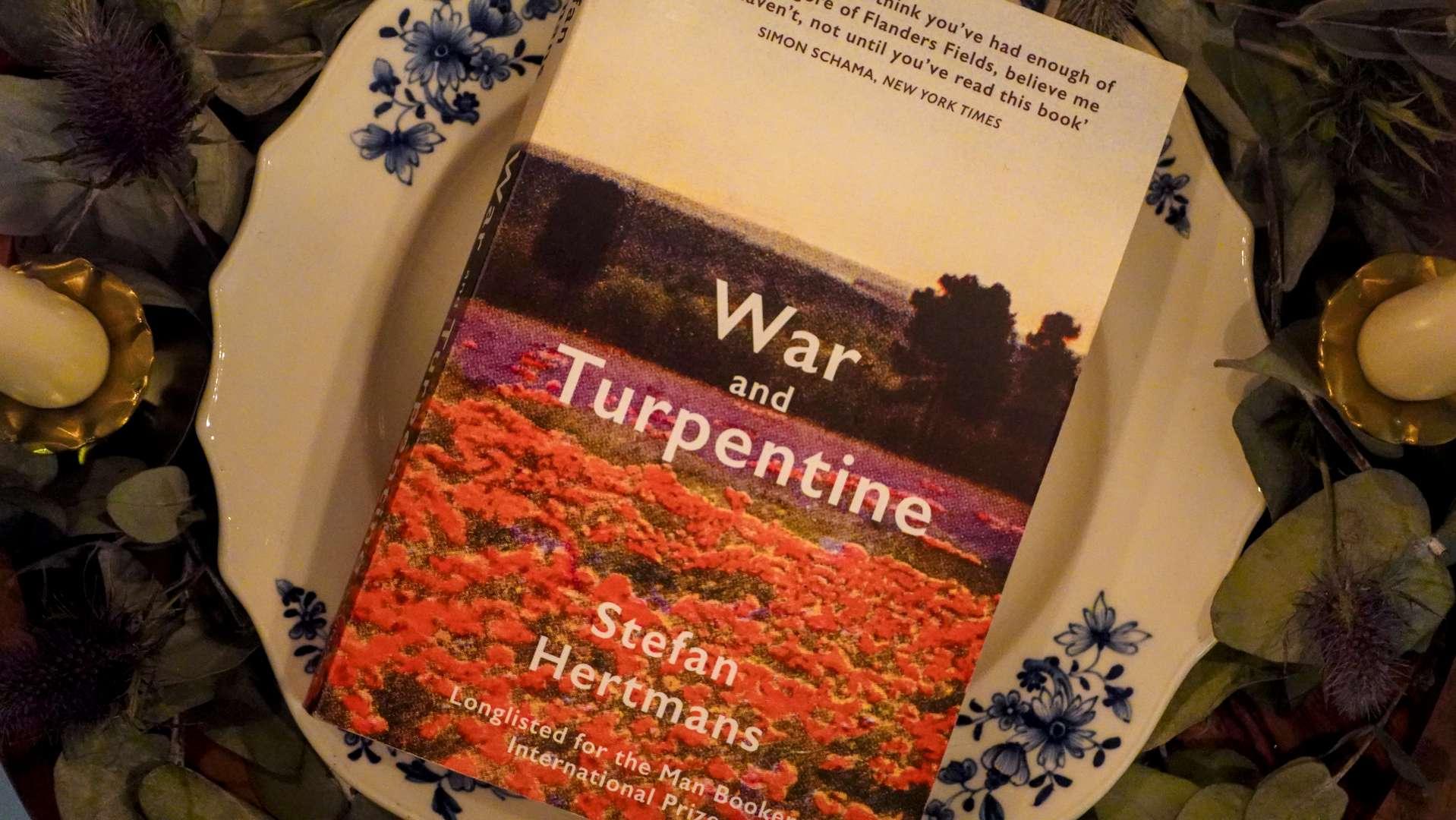

Stefan Hertmans’ War and Turpentine is a book about that transmission—about how one generation passes vision, memory, and meaning to the next. But it’s also something I didn’t expect at all when I picked it up: a meditation on working-class Flemish life that somehow achieves a kind of serenity I can’t quite account for.

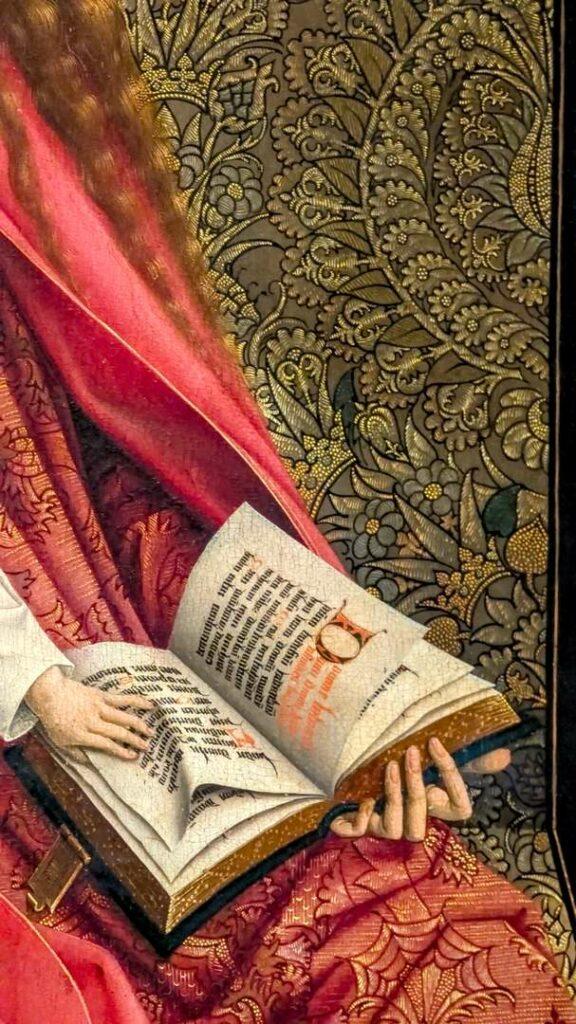

The novel—though “novel” feels like the wrong word for something so rooted in documentary truth—follows Hertmans’ grandfather, Urbain Martien, a painter and copyist who survived the trenches of World War I and left behind notebooks filled with memories, sketches, and observations. Hertmans discovers these notebooks after his grandfather’s death and uses them to reconstruct a life: a childhood in late 19th-century Ghent marked by poverty and violence, an ill-fated love affair, the unspeakable horrors of the Western Front, and the long, muted decades that followed.These were not easy lives. Urbain’s father, Franciscus—a church painter who restored religious frescoes and murals—was a brutal drunk. His mother worked herself to exhaustion. The world Urbain grew up in was one of backbreaking labor, casual cruelty, and the constant proximity of death. The war—when it came—was mechanized slaughter on an incomprehensible scale. And yet, reading Hertmans’ account of all this, I kept feeling something unexpected: peace.

Is it the writing itself? Hertmans’ prose has a gentleness to it, a kind of patient attention that refuses sensationalism even when describing atrocity. He doesn’t dramatize. He doesn’t inflate. He simply bears witness, with the same careful eye his grandfather brought to observing the fall of light on a trench wall or studying the paintings he would later copy. There’s a painterly quality to the sentences—the way Hertmans lingers on a detail, steps back to take in the whole composition, notices color and texture and the way memory itself distorts and preserves.

Or is it something in the Flemish character itself that comes through these pages? There’s a stoicism here, but not the cold, repressive kind. It’s more like a deep pragmatism, a sense that life is hard and beauty still matters, that you can witness horror and still notice how the morning light hits a cathedral spire. Urbain survives Passchendaele and Ypres—some of the worst fighting of the entire war—and what he chooses to record in his notebooks isn’t just trauma, but also the exact shade of blue in a sky glimpsed between explosions, the way frost formed on the rim of his helmet, the particular texture of paint his father used to restore a medieval fresco.

We’re told constantly that art isn’t vital. Culture budgets get slashed, school programs elevate STEM as essential and relegate the humanities to “nice to have.” But War and Turpentine is a quiet refutation of that entire framework. Here is a man who endured some of the worst circumstances imaginable—poverty, abuse, industrial warfare—and what kept him human, what allowed him to bear witness rather than simply shut down, was his ability to see aesthetically. Art wasn’t decoration for Urbain. It was survival. Not in any grand, redemptive sense, but in the most fundamental way: it gave him a reason to keep paying attention, to keep noticing, to keep finding meaning in a world determined to strip meaning away.

What Hertmans does brilliantly is honor that attention without romanticizing it. This isn’t a book that makes poverty noble or suffering redemptive. Instead, it takes seriously the inner life of someone who devoted himself to painting—a meticulous copyist, a man who loved art with quiet intensity even as practical circumstances shaped his artistic life.

And Urbain was an artist. His notebooks prove it. Not in grand gestures but in sustained observation, in his refusal to stop seeing even when seeing meant confronting the unspeakable.Hertmans, writing a century later, becomes his grandfather’s collaborator, finishing a project the older man began but couldn’t complete: transforming a life into testimony, memory into literature, private grief into something that can be shared. The book becomes what Urbain’s notebooks were: an attempt to preserve something fragile and essential, to say “this happened, this mattered, this is what it looked like if you paid attention.”

War and Turpentine isn’t an easy book, but it’s a generous one. It asks for your patience and attention, and in return, it offers something rare: a vision of how we might honor the dead not by monumentalizing them, but by seeing them clearly, completely, with all their contradictions and capabilities intact. And if you find yourself wondering, as I did, how Hertmans achieved this particular tone of gentle wisdom when describing such ungentle circumstances, well—perhaps that’s the mystery at the heart of all good writing. That language itself can become a form of grace, a way of looking that transforms what’s looked at.

See you tomorrow for Day 11 of our Belgian Literary Advent Calendar.

Until then, Merry Advent!

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 10th |

| Dear Friend, Urbain Martien kept notebooks. Through poverty, through a father’s brutality, through the trenches of World War I—he wrote things down. Not everything. That’s the point. He chose. What we pay attention to shapes us more than we realize. Not just what we see, but what we decide is worth seeing again. Worth preserving. Worth carrying forward into whatever comes next. In an age when we capture everything and remember almost nothing, I find myself thinking about that distinction. The difference between a camera roll full of images we’ll never revisit and a notebook entry we return to for decades. Between passive recording and active witness. Hertmans’ grandfather didn’t document his life—he curated it. He decided which moments deserved the labor of being transformed into words, which observations were worth the ink. And in doing so, he made a statement about what it means to be human: that we are not just what happens to us, but what we choose to hold onto. That selectivity feels almost radical now. We’re told to capture everything, archive everything, never miss a moment. But attention is finite. Memory is finite. And maybe the quality of our lives depends less on how much we record and more on what we decide matters. Where is your attention going, and is it going there by choice? Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.