Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 7

There are places in Brussels where the past doesn’t fade—it simply changes costume. The Galeries Saint-Hubert, completed in 1847, was Europe’s first covered shopping arcade, a glass-roofed marvel that preceded Milan’s famous Galleria by nearly two decades. Walking its length feels like stepping into an elegant parenthesis in time, where the 19th century vision of “everything for everybody” still echoes in the elegant cafés, chocolate shops, and jewelers that line its glazed corridors.

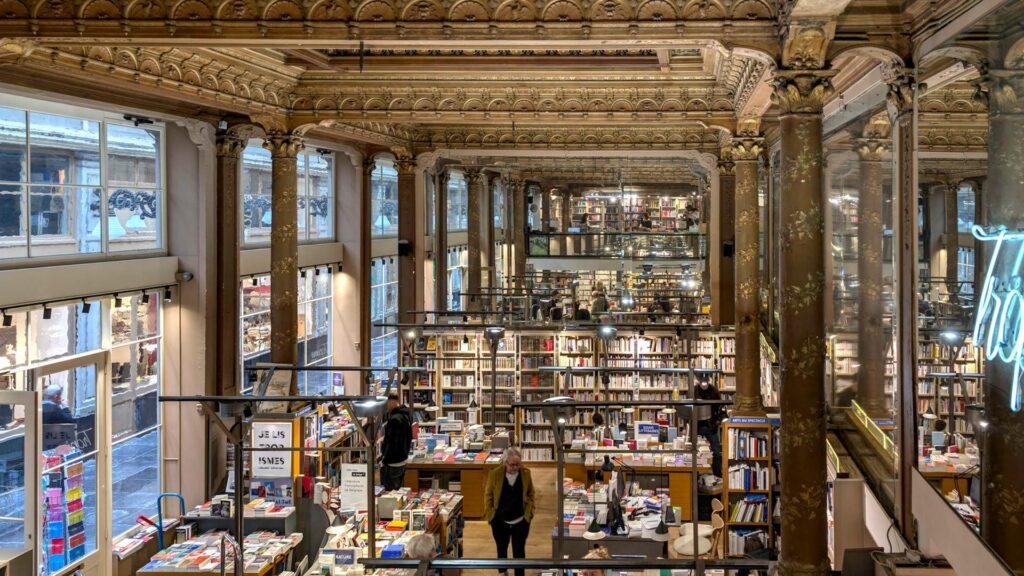

But it’s at the quieter end, in the Galerie des Princes, that I find what I’ve been searching for: Tropismes, a bookshop that tells the story of Brussels.

Before it became a temple to literature in 1984, this space was the Blue Note—one of Brussels’ legendary jazz clubs, where Belgian and international musicians filled these high-ceilinged rooms with improvisation and smoke. And before that, it was a dance school for Brussels’ elite, where the children of the bourgeoisie learned to waltz beneath ornate stucco ceilings. The bones of these former lives remain visible everywhere: the tall mirrors that once reflected dancers now reflect book spines; the gilded columns that witnessed jazz performances now stand guard over philosophy and poetry; the mezzanine where musicians once played now houses the children’s section, overlooking the entire space like a theatrical balcony.

As I push open the door, I understand immediately why this bookshop appears on every list of Europe’s most beautiful literary spaces. The room opens up before me like a revelation—soaring ceilings elaborately decorated with stucco work, enormous mirrors creating endless reflections of books and readers.

The ground floor holds contemporary literature, literary paperbacks, and thrillers—the current pulse of French-language fiction. I wander slowly, letting my eyes adjust to the abundance. Unlike the stark minimalism of modern bookshops, Tropismes embraces maximalism in the best sense: books are displayed on tables, propped on shelves, stacked with care. Handwritten notes from the booksellers dot certain covers—recommendations in blue ink, personal and unvarnished, the kind of guidance you’d get from a trusted friend rather than an algorithm.

I climb the narrow staircase to the mezzanine, where children’s books and comics create a riot of color against the architectural grandeur. From up here, looking down at the main floor, the mirrors multiply the space endlessly. It’s disorienting in the most wonderful way—you catch glimpses of yourself among the shelves, reflections within reflections, as if the bookshop exists in several dimensions at once.

I’ve come with a purpose: to find Belgian voices, writers who can guide me deeper into this country’s literary soul. My hands are soon full.

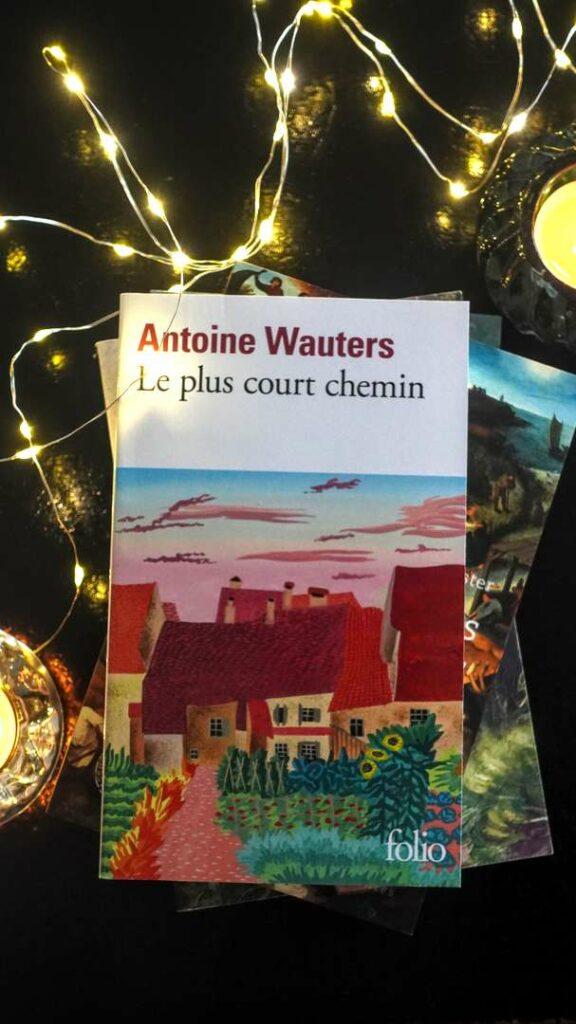

First, Antoine Wauters’ Le plus court chemin (The Shortest Path, not yet translated into English)—a meditation on childhood in the Belgian Ardennes during the 1980s. Wauters writes about memory the way some people write about landscape: as something both intensely personal and universally recognizable. This slim volume promises fragments of a rural Walloon childhood, reassembled by an adult writer trying to understand how those early years shaped everything that came after.

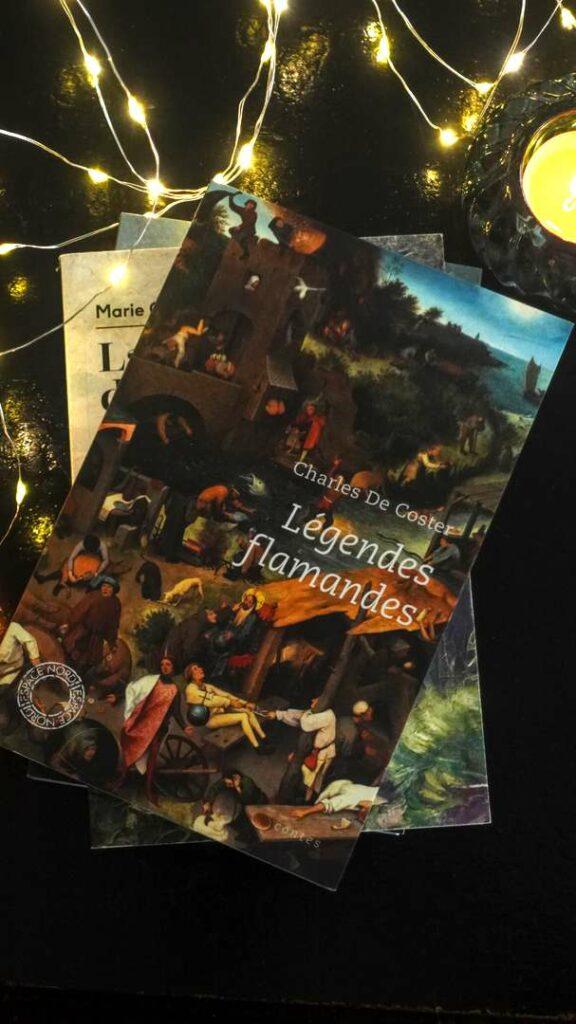

Next, Charles De Coster’s Légendes flamandes (Flemish Legends, available in English translation). Published in 1858, these tales are the precursor to De Coster’s masterwork, the legendary Ulenspiegel. Written in deliberately archaic French—channeling Rabelais and the 16th century—these are the folk stories of Flanders rendered with literary artistry. The bookseller’s note mentions their “merry truculence,” which feels like exactly what December needs.

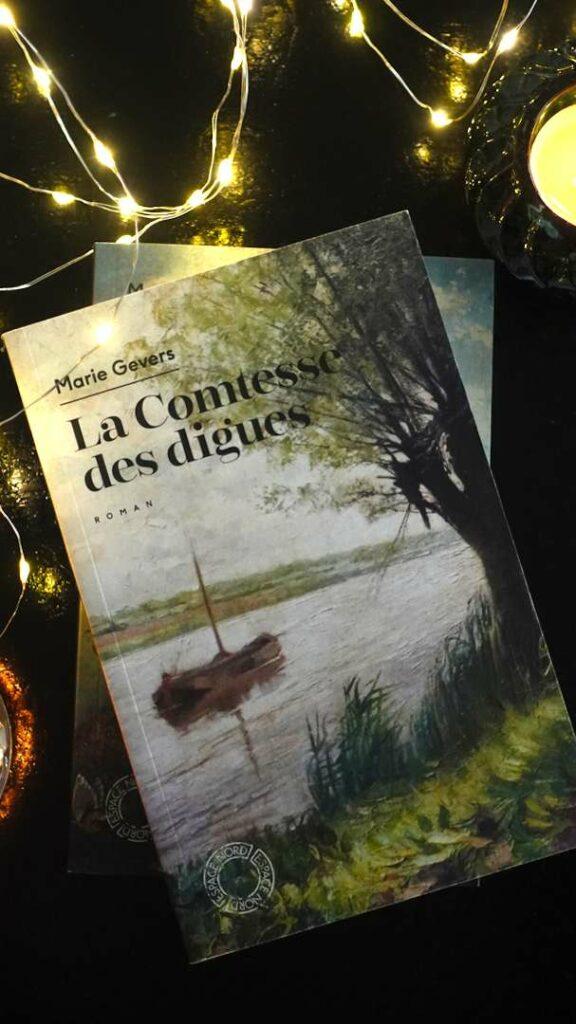

Then comes the book I’m most eager to read: Marie Gevers’ La Comtesse des digues (The Countess of the Dikes, not yet translated into English). Published in 1931, this is Gevers’ first novel, and it carries the landscape of her beloved Flanders like a watermark. The story follows Suzanne, who inherits her father’s title as guardian of the river dikes—a role traditionally held only by men. Torn between her love for the Scheldt River and the possibility of romantic love, Suzanne must choose her own path. Gevers was the first woman elected to Belgium’s Royal Academy of French Language and Literature, so I’m eager to know her prose.

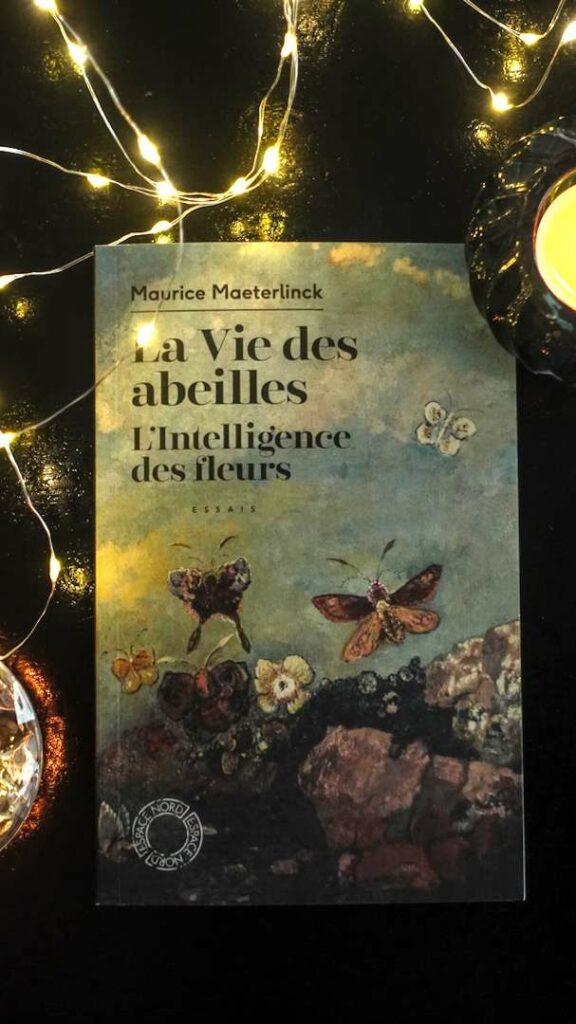

Finally, Maurice Maeterlinck’s La vie des abeilles and L’intelligence des fleurs (The Life of the Bee and The Intelligence of Flowers, both available in English). Published in 1901 and 1907 respectively, these philosophical essays marry natural observation with humanist meditation. Maeterlinck—Belgium’s Nobel Prize winner, symbolist playwright, and careful observer of the non-human world—wrote these long before anyone used the term “proto-ecological,” yet that’s precisely what they are. We’ll return to Maeterlinck later this month; for now, this volume promises a different way of seeing the world, one bee and one flower at a time.

I carry my stack to the register, where the bookseller wraps them with the care of someone who understands that books are promises of time yet to be spent. As I leave Tropismes, stepping back into the elegant corridor of the Galerie des Princes, I can almost hear the jazz echoing in the mirrors behind me—or perhaps it’s just the music that good bookshops always make, the quiet symphony of stories waiting to be read.

Outside, Brussels is decorated for Advent, but inside that remarkable room, time moves differently. The dancers are gone, the musicians have packed up their instruments, but the space remembers them all. And now it remembers books, and readers, and the conversations that happen silently between both.

Until tomorrow, Merry Advent !

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 7th |

| Dear Friend, I grew up believing that reading was the only reliable passport I would ever hold. In a country where borders were sealed and information was rationed, where even Western music arrived as contraband and conversations about the outside world happened in whispers, books were the one door that couldn’t be completely locked. They were smuggled, borrowed, passed hand to hand like secrets. And what we hungered for wasn’t just stories—it was proof that the world beyond our borders actually existed. That there were other ways of thinking, other ways of being human. So even if I didn’t experience the regime for long, I learned early on that literature wasn’t a luxury. It was survival. It was how you reminded yourself that your small corner of existence wasn’t the whole truth. It was how you kept your imagination from atrophying. That hunger never left me, even after the borders opened. Even after I could cross frontiers without fear. I still walk into bookshops the way some people walk into churches—with a kind of reverence, yes, but also with a desperate curiosity. What are people reading here? What stories matter in this place? What does this nation’s literature reveal about how its people see themselves and the world? Standing in Tropismes in Brussels, surrounded by shelves of Belgian writers I’d never heard of, I felt that old thrill again. The thrill of not knowing. Of being a stranger in someone else’s literary landscape. We’re often conditioned—gently, invisibly—to stay close to home in our reading. To favor books from our own country, written in our native language, reflecting our familiar experiences. It’s not wrong, this instinct. These books are mirrors, and we need mirrors. But if we only ever read within our own culture, we risk mistaking our reflection for the whole of reality. Most of us venture beyond our borders occasionally—when a prize winner catches our attention, when a Nobel laureate makes headlines, when the zeitgeist tells us a particular foreign author is worth our time. But how often do we truly immerse ourselves in another nation’s literature? Not just the blockbuster that’s been translated into thirty languages, but the quieter voices, the regional writers, the books that have shaped a culture from within? I could have walked into any international bookshop in Brussels and found the same bestsellers I’d see in Paris or London or New York. But that’s not why I came to Belgium. I came to find the books that belong here and nowhere else. The ones that will teach me how Belgians think about identity, about landscape, about the weight of history on a small country caught between larger powers. So yes, I buy Belgian books in Brussels. And when I travel elsewhere, I’ll do the same. Not because I’m collecting exotic trophies, but because I’m still that person who learned very young that literature is how we learn to be fully human—by discovering, again and again, all the ways there are to be alive in this world. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.