The Philosophy of Kaizen: Finding Patience in The Tsubaki Stationery Store

There is a Japanese concept called kaizen—改善—the philosophy of continuous improvement, of becoming one percent better every day. It is not about dramatic transformation or sudden genius. It is about patience, attention, the quiet work of refinement. I did not know I was practicing kaizen when I first picked up Ito Ogawa’s The Tsubaki Stationery Store. I only knew I was drawn to a story about letters, calligraphy and the kind of life that unfolds slowly, deliberately, in rhythm with the seasons.

By the time I finished reading, I had learned to write a kanji character, acquired my first glass pen and begun to understand something about the relationship between beauty and imperfection that I had been circling around for years without quite grasping.

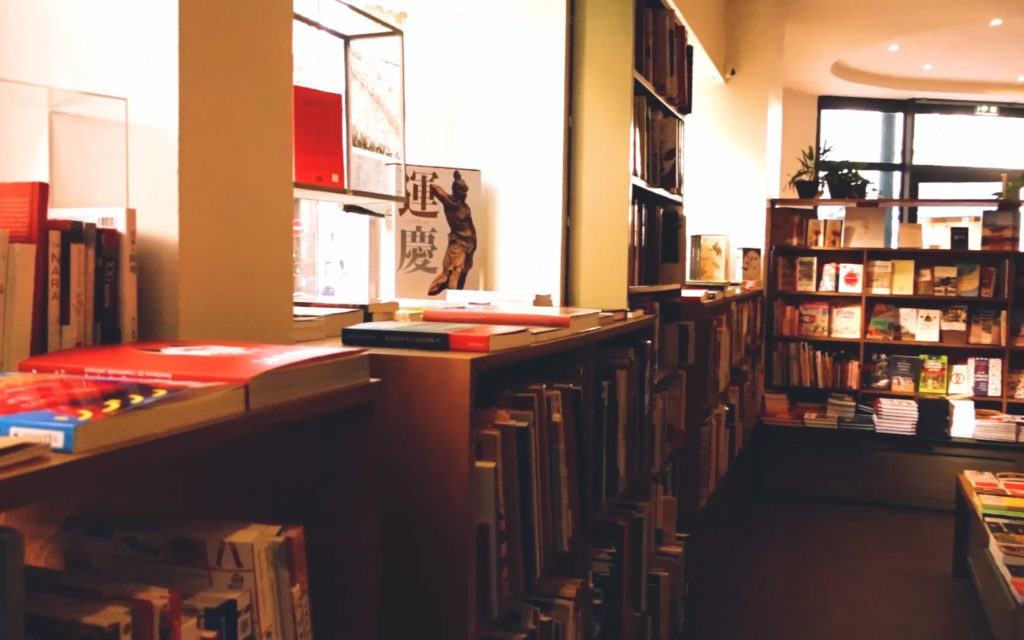

Visiting Junkudo and Moshi Moshi: Seeking the Soul of Japanese Crafts

Once I decided April would be my Japanese reading month, I knew I had to visit Junkudo, the place to be if you are a reader of Japanese literature in Paris. The moment I walked through the door, the noise of the street fell away. The silence was broken only by the occasional soft arigato from discreet customers moving between shelves. I had crossed a threshold into foreign territory—the kind of displacement only different alphabets can provide, where everything seems simultaneously fascinating and impenetrable.

I moved slowly through the categories. French and English translations appeared beside their Japanese originals, a quiet acknowledgment that not all of us can read the language but many of us long to enter its literary world. The gift shop corner held ceramic teacups and delicate notebooks. The bookmark and postcard stands were small galleries of woodblock prints and calligraphy. This modest selection only sharpened my appetite, so I crossed the street to Moshi Moshi, a shop specializing in Japanese crafts and traditional hobbies.

The ceramics were breathtaking. I had to exercise genuine restraint. But it was the stationery section that undid me—a small, carefully curated piece of Japan as I had imagined it. Perhaps this seems touristy to anyone actually from Japan, but when you are thousands of kilometers away from a culture you admire but cannot fully access, stepping into a shop like this feels less like consumption and more like pilgrimage.

I could not have found a better place to gather inspiration while reading about Hatoko, the young woman who inherits her grandmother’s stationery store and becomes a scribe for people who cannot find the words themselves.

The Ritual of Tea: Pairing Kukicha Karigane with Japanese Literature

Before entering the world of the novel properly, I made myself tea. Not ceremonial matcha, not yet—I was still at the beginning of this journey. Instead, I chose kukicha karigane from Le Parti du Thé, a blend I had been curious about for months.

Kukicha is made from the stems, stalks and twigs of the tea plant—the parts usually discarded in the production of more prestigious teas. This particular variety came from four different harvests: the first a selection of lower leaves from semi-wild plants, the second a winter harvest of thick stalks gathered only once every ten years, the last two from different spring pickings of fine young stems. When kukicha comes from the production of gyokuro—the most refined of Japanese green teas—it takes the name karigane.

The first sip transported me to a field of freshly cut grass beneath citrus trees. Every subsequent sip carried the essence of a tranquility that, in my perhaps romanticized imagination, could only be Japanese. This is what tea does when you are reading the right book at the right time: it becomes not just beverage but atmosphere, not just flavor but frame of mind.

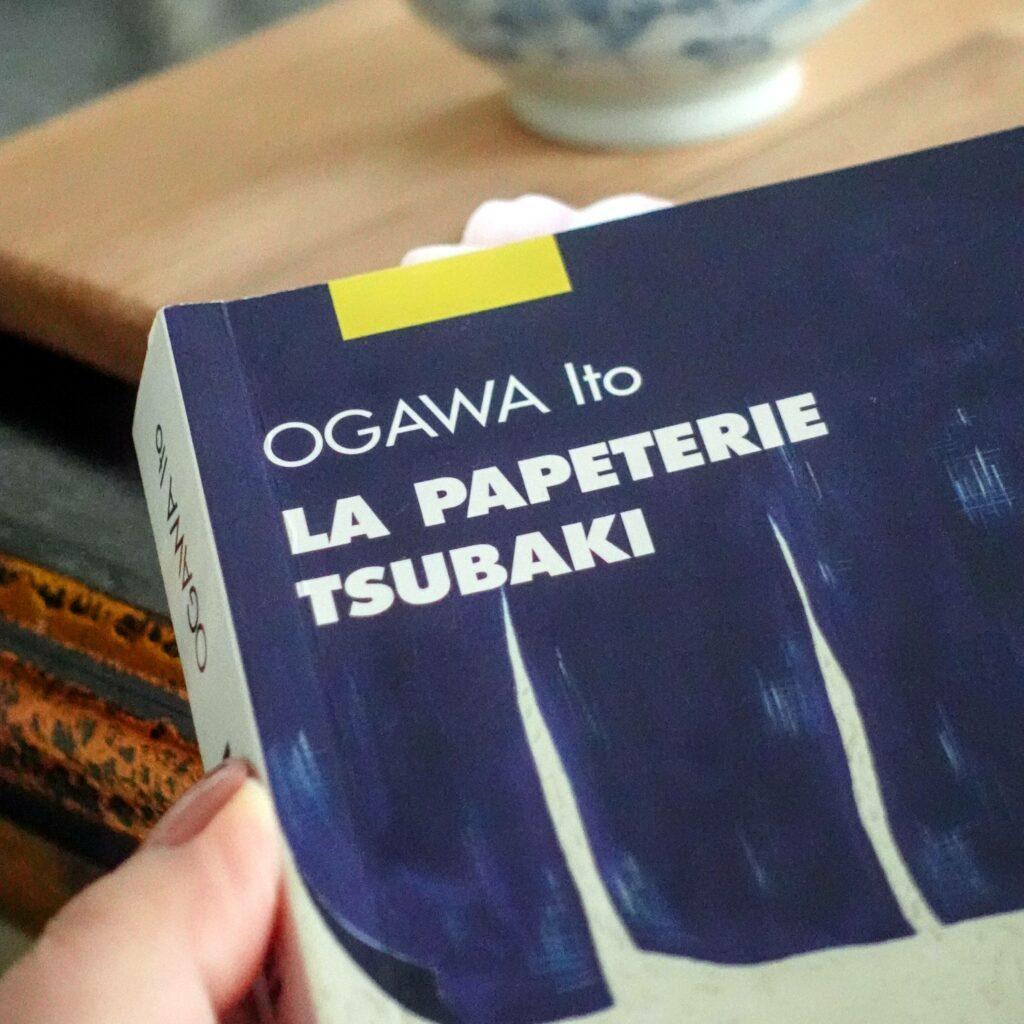

Review: Why Ito Ogawa’s Public Scribe is a Masterpiece of Slow Living

Ito Ogawa’s novel moves at the pace of its protagonist’s life. Hatoko returns to her childhood home to take over the family stationery store and the role of public scribe—a profession her grandmother held with quiet dignity. The book unfolds across seasons, describing a small community in contemporary Japan where modern life remains steeped in tradition.

The apparent simplicity of the story conceals how much it holds. This is a novel about mending broken family bonds, about inheriting a life you had not initially envisioned for yourself, about finding your passion through patient practice rather than sudden revelation. In the West, we wait for the stroke of genius, the moment of clarity, the dramatic turn. In Ogawa’s world, transformation happens through repetition, through showing up, through the accumulation of small, careful gestures.

Each chapter introduces a new client seeking Hatoko’s services as a scribe. A young man who cannot find words to apologize to his estranged father. An elderly woman who wants to thank a childhood friend. A businesswoman drafting a resignation letter that must be both honest and gracious. Through these commissions, we learn not just about letter writing but about the way Japanese culture prizes elegance in all circumstances—even, perhaps especially, in difficult ones.

Beyond the Page: Embracing Glass Pens and the Art of Kanji

I have noticed that certain books do not simply invite you to read them. They make demands. They ask you to prepare tea, to seek out specific foods, to try unfamiliar practices. The Tsubaki Stationery Store did this to me repeatedly.

At one point, Ogawa describes a picnic featuring inari zushi—rice tucked into pockets of sweetened fried tofu. The description was so vivid, so sensory, that I found myself walking to the Japanese market that same afternoon. As I ate them later, sitting by my window with the book open beside me, I felt simultaneously closer to this culture and overwhelmingly aware that I would never fully understand it. The paradox was not frustrating. It was clarifying. Proximity without possession. Appreciation without appropriation. This felt like the right relationship to have with a culture not my own.

For more than two years, I had been contemplating the purchase of a glass pen. I had admired them in shops, watched artisans craft them in videos, imagined what it would feel like to write with one. But I had never quite convinced myself. Then I reached the passage in Ogawa’s novel where she describes the invention of the glass pen by a Japanese craftsman in the late 19th century—how the spiral grooves inside the nib hold ink through capillary action, how each pen is hand-blown and therefore unique, how the act of writing with glass changes the quality of attention you bring to words.

That was enough. The decision made itself.

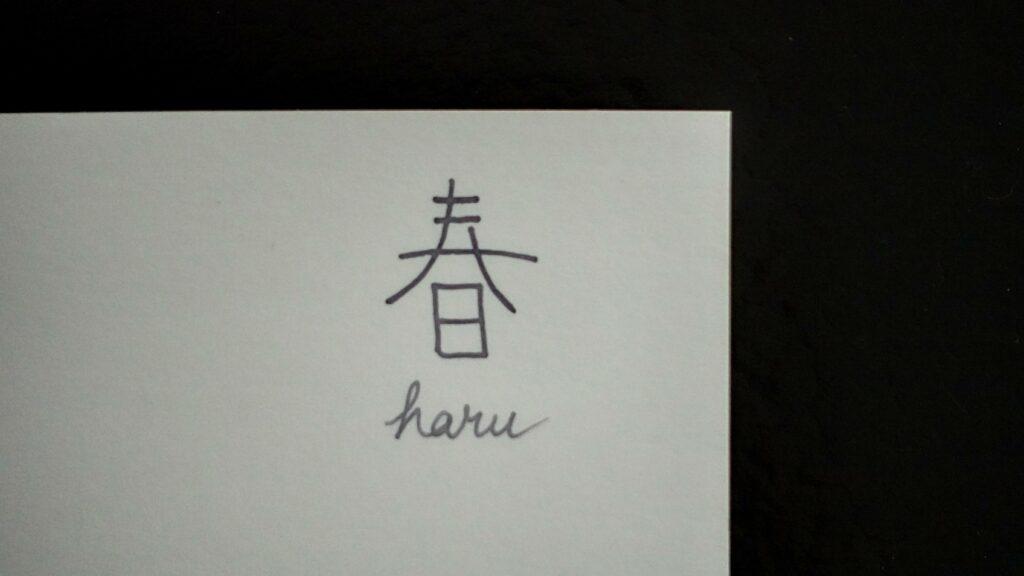

When the pen arrived, I had to choose what to write first. I considered trying it on handmade Japanese paper printed with traditional woodblock designs. I considered the postcard I had bought at Junkudo, a reproduction of an Ohara Koson painting. Finally, I decided to attempt the kanji for spring—春, haru—and mark it on the postcard as a memory for myself.

The Beauty of Imperfection: Learning the Kanji for Spring (Haru)

Learning to write even a single kanji character is humbling. What looks simple when demonstrated by someone fluent reveals itself to be a complex choreography of stroke order, pressure, angle and rhythm. I watched YouTube tutorials that made it seem effortless. I filled pages trying to gather the courage to write on the actual postcard. The glass pen felt unfamiliar in my hand. The ink pooled where I hesitated, thinned where I rushed.

And then I remembered a line from Ogawa’s novel:

The beauty of handwriting does not reside in its regularity, but in its warmth, its light, the silence and serenity that emanate from it.

I smiled. And then I wrote.

The character I produced was not elegant. It was not correct by any standard of accomplished calligraphy. But it was mine—a record not of mastery but of attempt, not of perfection but of presence. This is what kaizen actually means. Not flawless execution, but willingness to begin. Not genius, but one percent better than yesterday.

What the Book Teaches Without Teaching

The Tsubaki Stationery Store is not didactic. It does not lecture about mindfulness or aesthetics or the superiority of analog practices in a digital age. It simply shows you a woman writing letters with careful attention, drinking tea at the proper temperature, noticing the quality of light as seasons change. It shows you a community where people still commission handwritten letters for important occasions because they understand that medium matters, that the physical presence of ink on paper carries meaning that typed words cannot.

I finished the novel over the course of several weeks, returning to it in the evenings, reading a chapter or two before sleep. This felt appropriate. Ogawa’s prose does not reward speed. It asks you to slow down, to notice, to let the story settle.

By the time I closed the book, I had learned more than I expected—not just about Japanese culture or the history of stationery, but about the relationship between constraint and creativity, between tradition and personal expression, between the life we inherit and the life we choose.

I had also learned that the only ink color and brand Ogawa specifies in the entire novel is Herbin’s “Gris Nuage”—cloud grey—which happens to be my personal favorite. Coincidence? Perhaps. Or perhaps this is what happens when you read with full attention: the book finds you as much as you find it.

A Beginning, Not a Conclusion

This was my first encounter with Ito Ogawa’s work, but not my last. The Tsubaki Stationery Store has not been translated into English, though some of her other novels have. If you are curious about contemporary Japanese literature that values quietness over drama, interiority over action, seasonal rhythms over plot urgency, her work offers a gentle entry point.

I still have the postcard with my amateur attempt at the kanji for spring. It sits on my desk, a reminder that beauty does not require perfection. That becoming one percent better is enough. That sometimes the most meaningful transformations happen not through dramatic revelation but through small, repeated gestures of attention.

Kaizen. Continuous improvement. One stroke at a time.

The Reading

The Tsubaki Stationery Store by Ito Ogawa (translated into French as La Papeterie Tsubaki) — Momox Shop FR

A quiet, seasonal novel about a young woman who becomes a professional scribe, writing letters for people who cannot find the words themselves. While many are searching for The Tsubaki Stationery Store English translation, the book is currently a treasure for those who read Japanese or French (La Papeterie Tsubaki) – English translation announced for July 2026.

The Experience

Tea: Kukicha Karigane from Le Parti du Thé — a rare Japanese green tea made from stems and stalks, with a fresh, grassy flavor and remarkable tranquility.

Bookshop: Junkudo Paris, 18 Rue des Pyramides, 75001 Paris — a small haven of Japanese literature and stationery in the heart of the city.

Craft Shop: Moshi Moshi, 16 Rue d’Argenteuil, 75001 Paris — Japanese ceramics, textiles and traditional papers.

F.A.Q.

What is “The Tsubaki Stationery Store” by Ogawa Ito about?

It is a heartwarming novel about Hatoko, a young woman who returns to her hometown of Kamakura to take over her grandmother’s stationery shop. As a “public scribe,” she writes deeply personal letters for others, using specific pens, ink, and paper to convey the perfect emotion, while slowly healing her own past.

Is “The Tsubaki Stationery Store” available in English?

While the book gained massive popularity in Japan and France (La Papeterie Tsubaki), English readers should look for the translation by Cat Anderson. It is a must-read for fans of slow-paced, atmospheric Japanese literature like The Before the Coffee Gets Cold series.

What is a public scribe in Japanese culture?

In the novel, a public scribe (Yubinya) is more than just a ghostwriter. They are artisans who choose every detail—from the postage stamp to the specific calligraphy style—to match the sender’s intent, whether it is a letter of condolence, a business greeting, or a delicate family apology.

Why is stationery so important in the book?

The book highlights the Japanese concept that the “soul dwells in written words.” Ogawa Ito describes the physical tools of writing—glass pens, washi paper, and custom inks—as essential elements of human connection and mindfulness.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.