Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 6

A short note on how and why I share book links

There are countries you love because you were born in their legacy. And then, there are the countries you choose to love with deliberate passion. I should know, since this is precisely my story.

Tonight, we’ll speak of one of my favourite contemporary writers—a man who declared in an interview:

“De même qu’on appartient à sa famille et qu’on choisit ses amis, je viens de France et j’ai choisi la Belgique.”

The same way you belong to a family but choose your friends, I come from France and I chose Belgium.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt writes with a sensitivity I’m particularly receptive to. His novels are always evocative—not only of places or people, but of those subtle feelings that guide our existence, as if his artistic superpower were the ability to name the precise emotional state that corresponds to every situation. He writes in the language of the heart, where longing meets understanding, where sorrow transforms into grace.

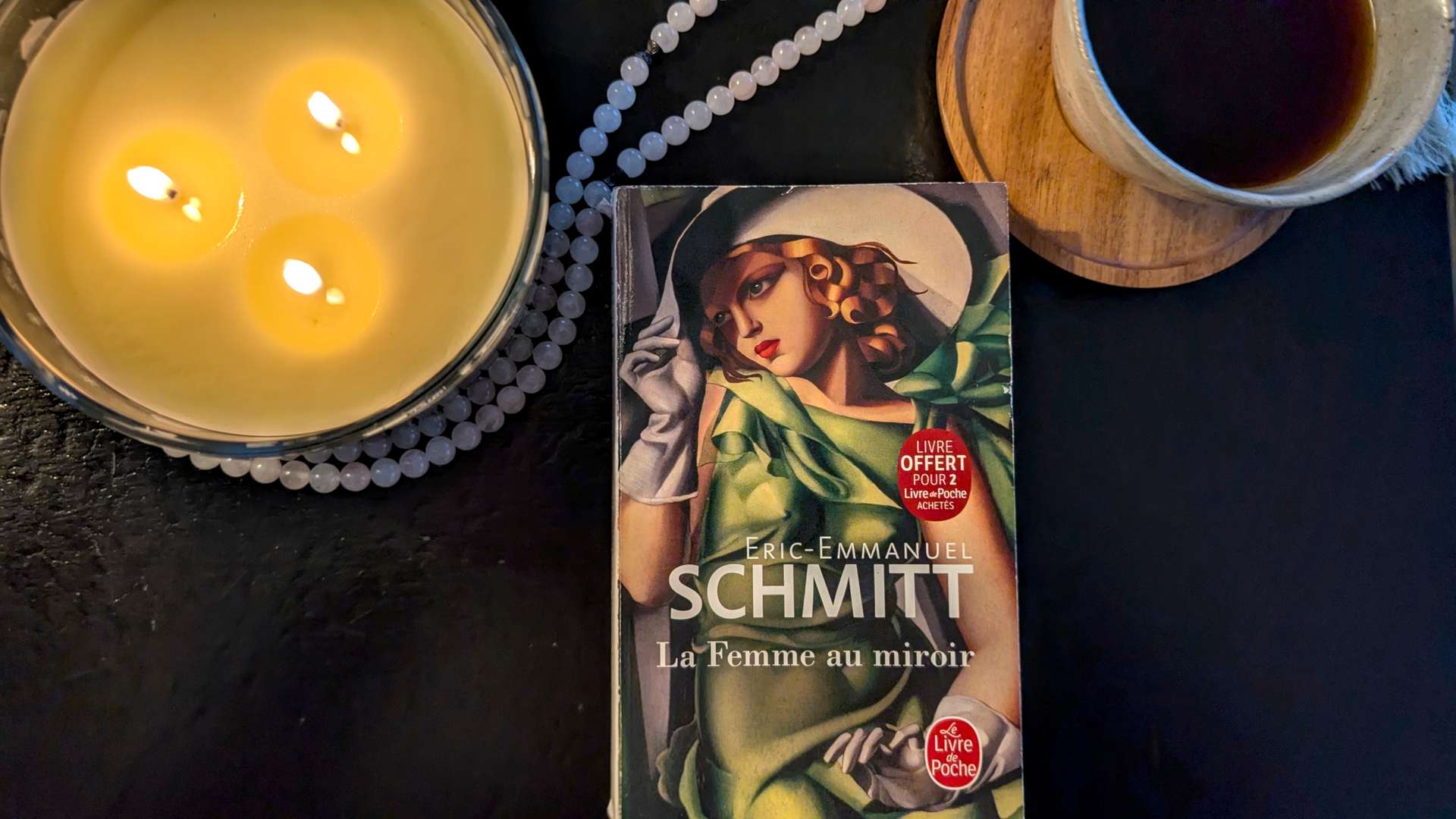

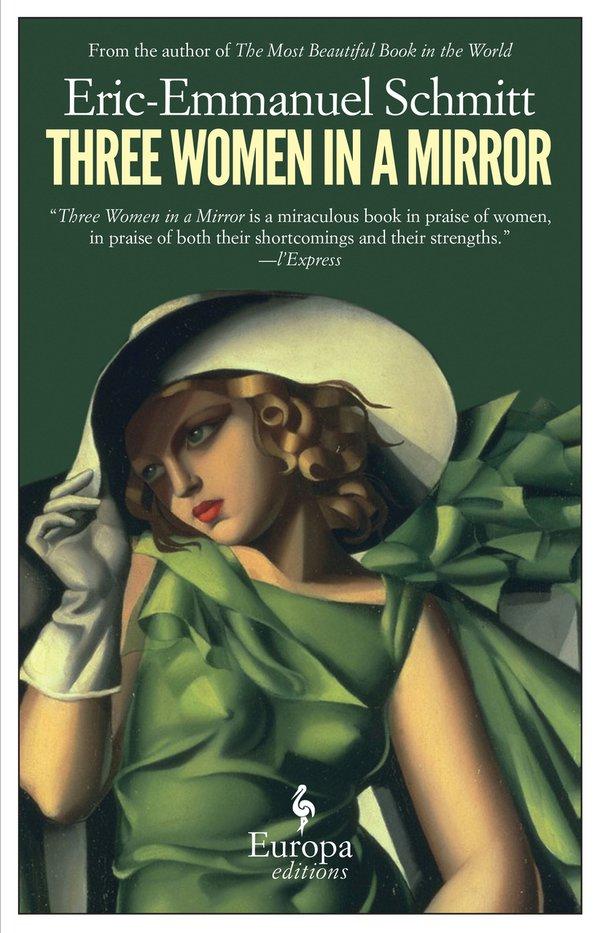

For my Belgian adventure, I chose a novel that would immerse me in his vision of the culture. What I found became an instant favourite, one to place high up on my shelf of the greats: La Femme au Miroir, translated into English as Three Women in a Mirror.

The novel weaves together the lives of three distinct women separated by centuries but united by a singular, profound sense of alienation from the roles society has forced upon them.

In Renaissance Bruges, Anne is a dreamer who feels a mystical connection to nature and flees a forced marriage to escape the strictures of her community. In turn-of-the-century Vienna, Hanna is a wealthy but emotionally detached aristocrat who turns to the budding science of psychoanalysis to understand why she rejects domesticity. And in modern-day Hollywood, Anny is a world-famous superstar who uses drugs to cope with the hollowness of her fabricated public persona.

Alternating between these three timelines, the novel follows their parallel struggles as they confront the “mirror”—the disconnect between their external images and their internal truths—and risk everything to break free and find their authentic selves.

Each story felt so evocative of women’s destinies that remain contemporary despite the centuries between them. I recognised friends. I recognised myself at times. The narrative of what it means to be a woman in the world, I realized, is as old as time itself.

And I couldn’t help but feel grateful that this story was written by a man—proof that women’s concerns are, more than ever, everyone’s concerns. That empathy need not wear a single face. That understanding can cross even the oldest boundaries.

This is the type of novel one could spoil by revealing too much. So without going into detail, I’ll say only this: the Renaissance story of Anne was the one that moved me the most—especially since it revealed a social aspect of European society I wasn’t aware of: the beguinage.

During my recent stay in Bruges, I knew I had to see it for myself.

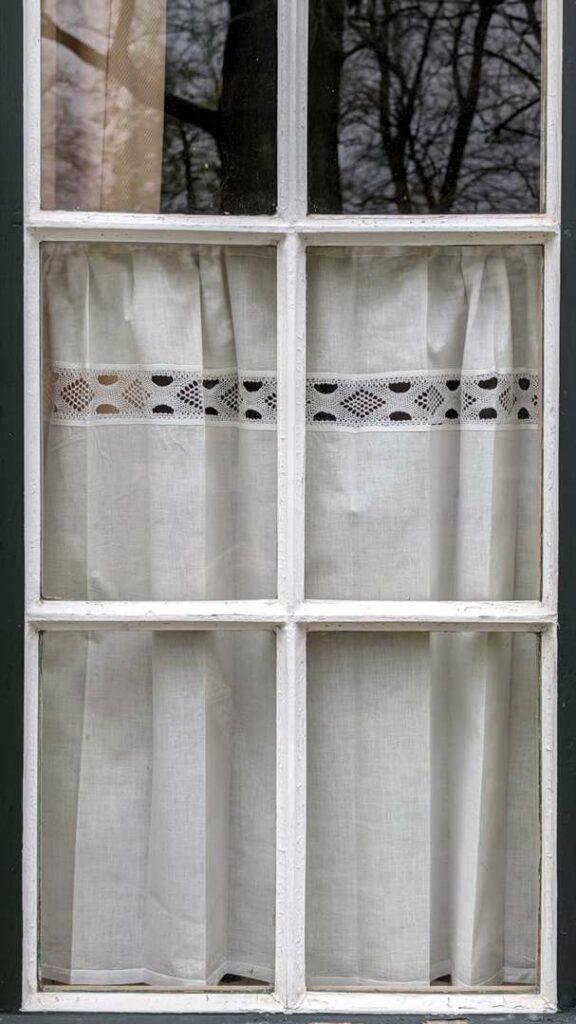

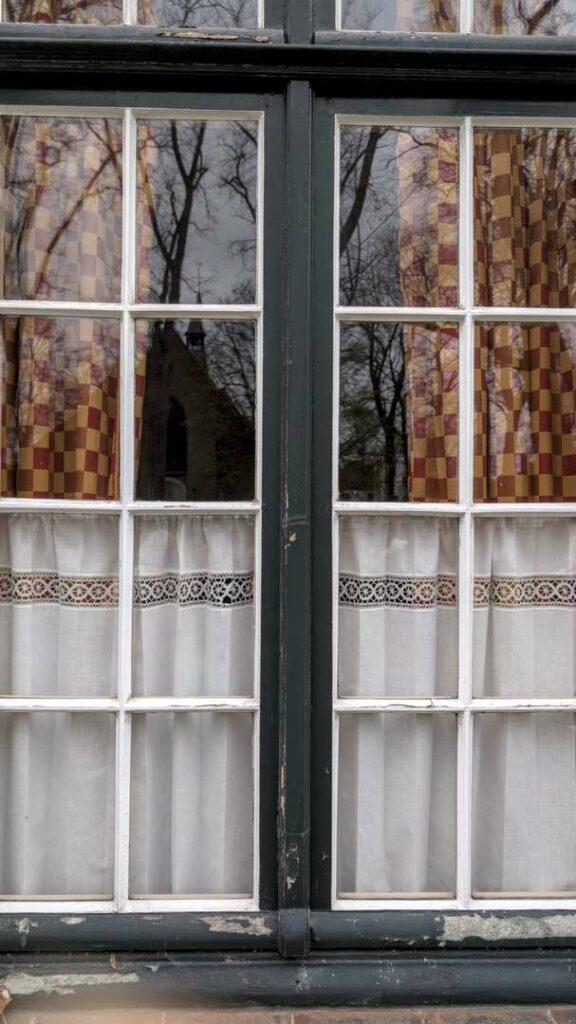

Beguinages were semi-monastic communities where women, called beguines, lived together in devotion and service, but without taking permanent vows. Unlike nuns bound to convents, these women retained a measure of autonomy: they could own property, leave if they wished, pursue contemplative lives without surrendering entirely to institutional rule. It was a radical space of feminine independence in medieval Europe—quiet, unassuming, revolutionary in its ordinariness.

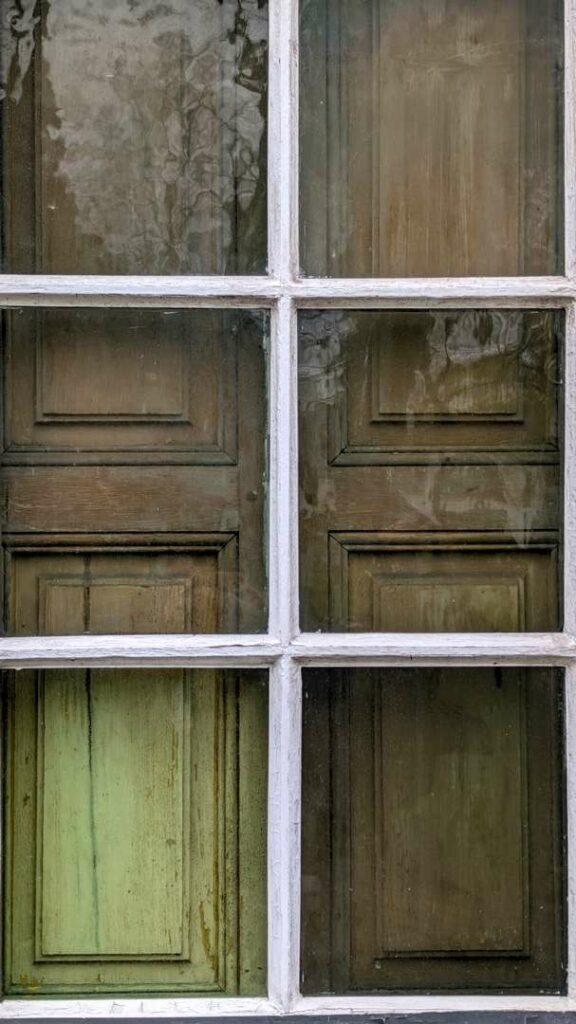

The Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaarde in Bruges, founded in 1245, still stands today—a tranquil enclave of whitewashed houses arranged around a central green, its simplicity almost startling against the grandeur of the city beyond its walls. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the beguinage no longer houses beguines themselves. Instead, a small community of Benedictine nuns now inhabits the space, preserving its spirit of contemplative silence.

The atmosphere today is slightly less peaceful, unfortunately. Tourist groups visit the beguinage daily—it’s open to all, free of charge—but their guides don’t always provide the context needed to understand that this is a place of silence. Still, when you manage to move away from the crowds, when you slip into one of the quieter corners or pause beside the small chapel, you can recreate the atmosphere in your mind. You can feel what it must have been like to live here: a life measured not by ambition or spectacle, but by breath, by prayer, by the soft rhythm of days passing like water.

Moving between the houses of the beguines I thought of Anne. A destiny of enlightenment that went beyond reason. An instinctive connection to a divinity that needs no definition, cult, or worship. She is a woman who finds God not in doctrine, but in stillness. Not in sermons, but in the space between words.

Schmitt’s character embodies what I believe to be the most authentic form of spirituality: the kind that flows freely between what we define as the self and the rest of the world, until its perpetual flux unites everything into the obvious—that we are all but one. That separation is the illusion. That love, in its truest form, is simply recognition.

Walking in silence, feeling the ancient cobblestones under my feet, I was filled with gratitude for the beauty this novel revealed to me. Three destinies united by an eternal energy, one that comes from the beginning of time, the same one that moves me to tears as I close the book, and that will continue to nourish the world long after we’re gone.

Translated into more than a dozen languages, this is a book that will move you, enchant you, make you see the women in your life in a different light—and perhaps allow you to understand yourself a little better. It’s the kind of novel that doesn’t shout its wisdom but offers it gently, like a hand extended in the dark.

Tomorrow, we’re pursuing pleasure instead of contemplation: I’m taking you shopping—to one of the most beautiful bookshops I’ve visited. A place where stories live in the historic walls as well as between the pages.

Until then, Merry Advent.

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 6th |

| Dear Friend, I’ve been thinking about revolutions—not the loud kind, the ones that storm barricades and rewrite constitutions, but the quieter ones. The ones that happen in whitewashed houses arranged around a central green. The ones no one notices until centuries later, when historians look back and wonder: how did they manage that? The beguines of medieval Bruges didn’t ask permission. They didn’t write manifestos or demand recognition. They simply… chose differently. They created a life that allowed them autonomy without requiring them to sever every tie to the world. They lived in devotion, but on their own terms. They could own property. They could leave if they wished. They existed in a space that shouldn’t have been possible for women in their time—and yet there it was, tucked quietly between the grand cathedrals and the merchant houses, unassuming in its revolutionary ordinariness. Walking through the Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaarde, I kept thinking: this is what it looks like to simply take the space you need, without announcing it. Without justifying it. Without waiting for the world to grant permission. There’s something deeply powerful in that silence—not the silence of suppression, but the silence of refusal to engage with systems that would diminish you. The beguines didn’t argue with the institutions that sought to define women’s lives. They just stepped aside and built something else entirely. I think about this often in my own life: the moments when I’ve stopped explaining myself, stopped seeking validation for choices that feel true. The times I’ve cultivated my own silence—not as absence, but as presence. A deliberate withdrawal into a space where I can breathe on my own terms. It’s not always dramatic. Sometimes it’s as simple as closing a door. Choosing a different rhythm for your days. Letting certain expectations fall away without ceremony. Living in a way that doesn’t announce itself but simply is. The beguinage reminded me that revolution doesn’t always need to be loud to be real. Sometimes the most radical act is the quiet one: building your life according to an inner architecture that no one else can see, but that holds you nevertheless. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.