侘寂

Wabi-sabi

a way of living that focuses on finding beauty within the imperfections of life

and accepting peacefully the natural cycle of growth and decay

The Japanese dry garden (枯山水, karesansui) was invented by Zen monks around the 14th century , and hasn’t changed much ever since. The miniature version of a garden, with gravel or sand, rocks, moss and the odd pruned tree, is, like many Japanese traditions, a symbol that invites both the creator and the admirer to find meaning. A zen garden is usually meant to be seen from a single viewpoint, outside of the garden, so the entire intention of the exercice is deliberate. Like a theatrical mise-en-scene, nothing is subject to chance, except maybe for the light, and even that…

The intention is to imitate the essence of nature and not its appearance, thus inviting the viewer to meditate on the true meaning of existence.

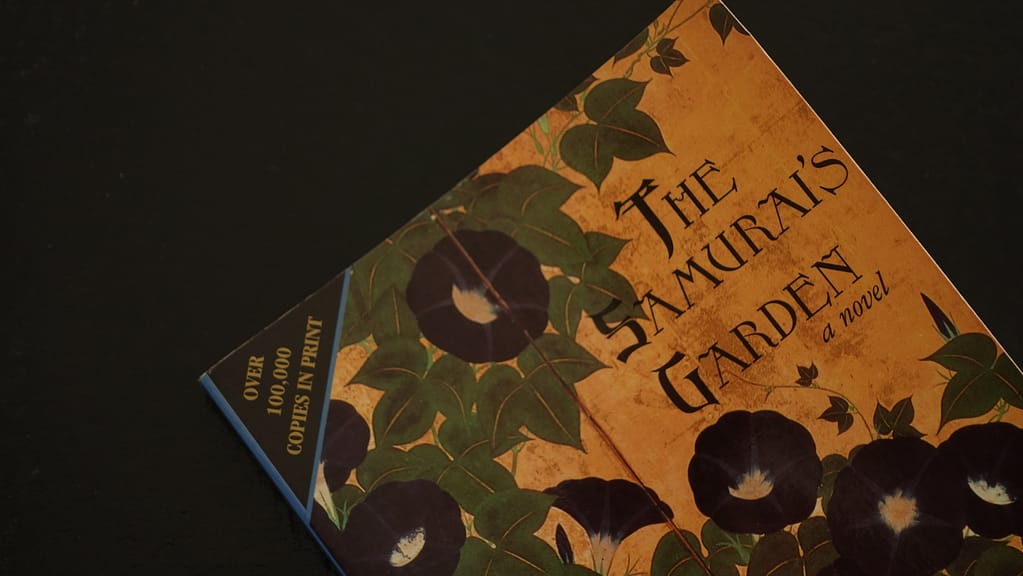

My mini zen garden has brought me just a step closer to this concept, while I was reading a novel of discoveries and introspection : The Samurai’s Garden, by Gail Tsukiyama.

“Please, Matsu-san,’ I told him, not long after the house was completed. ‘I don’t wish to have any flowers.’

Gail Tsukiyama, The Samurai’s Garden

“Never once did he question me. I needed my life to be simple without any beauty to remind me of all I had lost. And though I had not told him that, Matsu must have seen it in my eyes. ‘Don’t worry, Sachi,’ he said, ‘there will be no flowers.”

Gail Tsukiyama was born in San Francisco from a Chinese mother and a Japanese father. So when she places a Chinese character, on a year-long holiday in Japan, we can easily imagine that none of the details are a coincidence. Young Stephen is recovering from tuberculosis, so he flees the hot and humid climate of Southern China to take refuge in his family’s holiday home, in a Japanese coastal village. He is attended by Matsu, the housekeeper and master gardener, who proves to be the spiritual guide our Young Stephen needed.

The setting is so beautifully described, between the layout of a Japanese house, the garden tended with such care, the small village life and the sharp beauty of a solitary beach, you not only feel transported, but you appreciate a writing made for a Western approach, with a subtle understanding of Eastern philosophy. I think this is what makes this novel special for me : its vision is not as foreign as that of a born and raised Japanese, and yet it has the power to bring me closer to a different way of perceiving the world. Much like Stephen, I find myself in the role of the apprentice, trying to absorb as much wisdom as possible from Matsu :

“The garden is a world filled with secrets. Slowly, I see more each day. The black pines twist and turn to form graceful shapes, while the moss is a carpet of green that invites you to sit by the pond. Even the stone lanterns, which dimly light the way at night, allow you to see only so much.”

Gail Tsukiyama, The Samurai’s Garden

A training of your attention to detail, to the invisible, a therapy of beauty no matter the context, the novel stands as an alternative to our sometimes simplistic way of evaluating situations. The steady calmness of Matsu is a lesson of life purpose for all those who chase the job, the social recognition, the title that might give meaning to their life. The book has the same effect on the reader as the fresh sea air that soothes Stephen’s lungs : a quiet and solitary moment, worth a thousand cures.

Guided by this moving novel, I came to visit one of my favourite gardens, just on the outskirts of Paris, in the very chic city of Boulogne-Billancourt. The gardens of the Albert Kahn museum.

Albert Kahn was a French banker and philanthropist, born in 1860 in the family of a jewish cattle dealer. After finishing high-school, he started work as a bank clerk in Paris, while continuing his studies in the evenings. He began meeting intellectuals from different backgrounds, and by the time he joined Goudchaux Bank as an associate, he had a solid circle of devoted friends in the arts. From his many journeys he gathered the most important collection of autochromes in the world, and the idea of a garden like no other.

On the 10 acres of land that the property in Boulogne offered, he commissioned the best landscape architects to create a diverse and fascinating oasis, from the jardin à l’anglaise, to the French garden, a blue forest and a golden one, and of course the famous Japanese garden. The feeling you have when walking around is of complete and utter fascination. In a relatively small space, there is such a multitude of species, such a diversity of perspectives, everywhere you look there is a picture perfect scene. Serene, reflective, a meditation on the beauty of nature. Just like a Samurai’s garden…

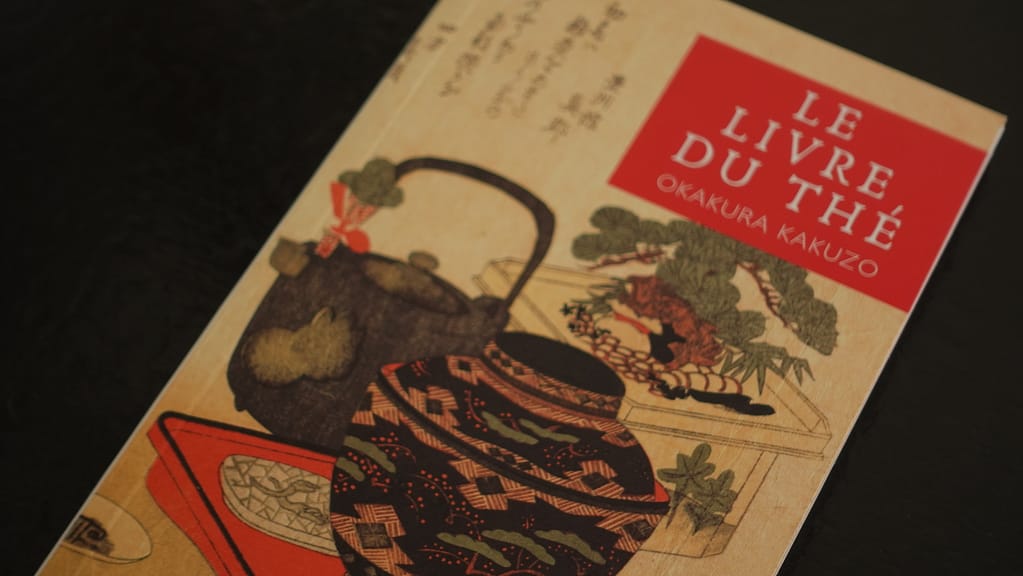

The thing with good storytelling is that it stimulates my curiosity in such a manner, I become quite the explorer… and with the traditional Japanese tea houses in the gardens, the idea of a chado or Japanese tea ceremony became more and more tempting. This is by no means a proper chado, I would never claim to be an expert in such an intricate and ancient ritual, but I did try my best at making a memorable Japanese tea for one. For the technique, YouTube has been my main source of information, and an extensive one for that. As for the philosophy, I found my joy in the famous Book of Tea, by Okakura Kakuzo. The book won’t tell you about the types of tea or the perfect temperatures for steeping, it will lift your spirit towards the essence of this art.

“Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence. It inculcates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the Imperfect, as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.”

Kakuzo Okakura, The Book of Tea

I found out for instance, that it was during the Song dynasty in China that powdered tea became fashionable, along with a more rudimentary method of whipping it. The Japanese have adopted the habit, while the Mongol invasions in China have forever changed the local customs and the powdered tea never came back in fashion. In that respect, the Japanese cha-no-yu is a descendent of a ceremony more than 1000 years old. So now, as I am trying my best to honour the matcha I have before me, I am aware of the piece of history I am attempting to revive, so a moment to gather my thoughts and channel my spirit is necessary.

“The tea-masters held that real appreciation of art is only possible to those who make of it a living influence. Thus they sought to regulate their daily life by the high standard of refinement which obtained in the tea-room. In all circumstances serenity of mind should be maintained, and conversation should be conducted as never to mar the harmony of the surroundings. The cut and color of the dress, the poise of the body, and the manner of walking could all be made expressions of artistic personality. These were matters not to be lightly ignored, for until one has made himself beautiful he has no right to approach beauty. Thus the tea-master strove to be something more than the artist,—art itself.”

Kakuzō Okakura, The Book of Tea

With an intention of symmetry, so unspecific to the Japanese culture, I will circle back to the wabi-sabi concept I mentioned at the beginning of this video, and I’ll leave you with this image :

“Much has been said of the aesthetic values of chanoyu- the love of the subdued and austere- most commonly characterized by the term, wabi. Wabi originally suggested an atmosphere of desolation, both in the sense of solitariness and in the sense of the poverty of things. In the long history of various Japanese arts, the sense of wabi gradually came to take on a positive meaning to be recognized for its profound religious sense. …the related term, sabi,… It was mid-winter, and the water’s surface was covered with the withered leaves of the of the lotuses. Suddenly I realized that the flowers had not simply dried up, but that they embodied, in their decomposition, the fullness of life that would emerge again in their natural beauty.”

Okakura Kakuzo, The Book Of Tea

Until next time, enjoy your reading and your rituals !

If you would like to support The Ritual of Reading, please consider purchasing your books from the Bookshop.org dedicated site by clicking the link below. You get to support local bookstores and I make a small commission with every purchase. Thank you !