Elif Shafak’s There Are Rivers in the Sky, Babylon at the Louvre and the Deep Blue of Lapis Lazuli

For most Europeans I know, Antiquity evokes Ancient Greece or the Roman Empire — civilizations that feel closest and most familiar. It’s natural to keep our historical footing rooted in the ground beneath us. However, the Internet has disrupted these natural tendencies, making it possible to explore unfamiliar cultures without being a scholar buried in a library. Even in simplified forms, the knowledge it offers can be profoundly eye-opening, in this case, about Antiquity farther than those two great European powers.

Mesopotamia is a rather abstract notion for the non specialists, taught (in my opinion) too early in school, at an age when children are hardly grasping current events, let alone imagine what the year 2000 BC looked like. This was the case for me, and while I kept a notion of the cradle of humanity, earliest civilization known to us, etc., things were left somewhere waiting, for the right time to dive deeper into the subject.

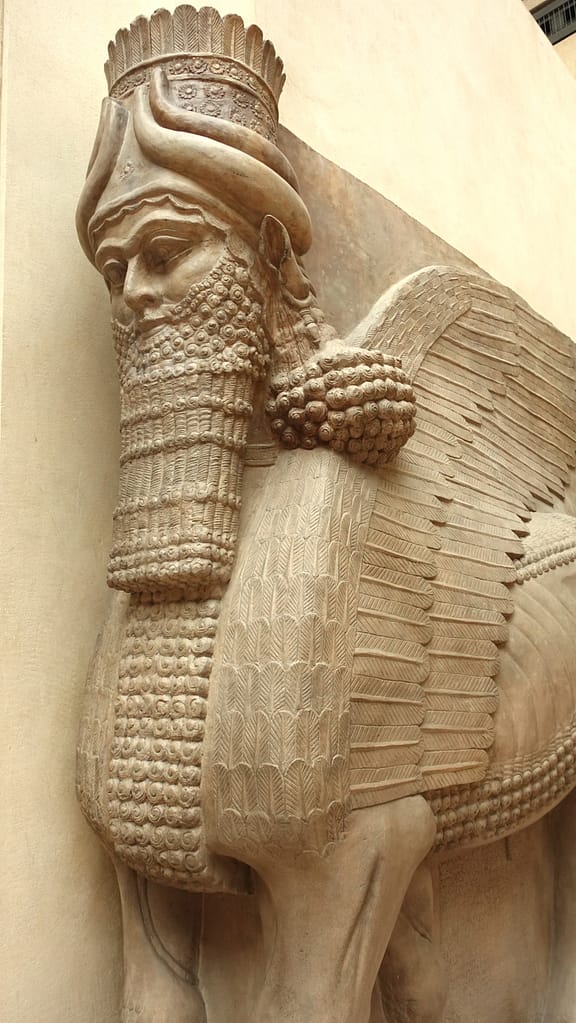

The Louvre’s Babylon: A Lion in Passing, A Love Everlasting

I’m slowly finding my way into Mesopotamian culture, and in the last few years I’ve been approaching it with caution, through several visits to the Oriental Antiquities department of the Louvre, where one piece in particular, drew my attention.

My love of cats is notorious, and even if I’m not an adventurer when it comes to larger felines, I find them absolutely fascinating. That must be the reason why the Passing Lion, this decorative glazed-brick panel feels so familiar despite its extensive history.

Imagine this : on a scorching summer afternoon, you arrive on the outskirts of Babylon, the main cultural and political city of the area. The year is 500 BC. You make your way towards the eighth gate to the inner city, the Ishtar Gate, built not long ago by the King Nabuchodonosor. The construction stands majestically, in all its dark blue splendour, at the end of a road, the Marduk Processional Way, designed with brick and polychrome images of animals and Gods, each one representing a strong symbol for the Babylonians. The road is almost a kilometer long, so you take a break mid way, to catch your breath, and there, you notice the Lion.

A symbol of the goddess Ishtar, the Lion is omnipresent in the Babylonian culture. She stands as a reminder of power and overcoming adversity, something you can relate to wherever you find yourself on the planet. Her mouth is open, yet you don’t feel frightened. She seems as thirsty as you are, but nothing can stand in her way.

They call her The Passing Lion, but only you know she’s a Lioness, you’ve met her before, in a distant dream. You’re still a mortal, while She is the symbol that will live for thousands of years, her colours slightly fading, her home much farther than her birthplace, she’s seen the world and the world saw her, and you don’t know it yet but you will meet once more, in the heart of Paris.

My fascination with the Passing Lion is at a crossroads between the analytical mind and the vibration of the soul. I am of course in awe at the thought that this beauty survived for 2500 years, that so much of the colour glaze is still intact, and that a culture long gone survives in spirit through art. But then I clear these thoughts and I can hear her breathing. It’s not a roar, more of a panting breath, rhythmic, hypnotising. Made out of clay and coloured glaze, her life force is greater than our imagination.

She is my protector, the Lioness of Babylon.

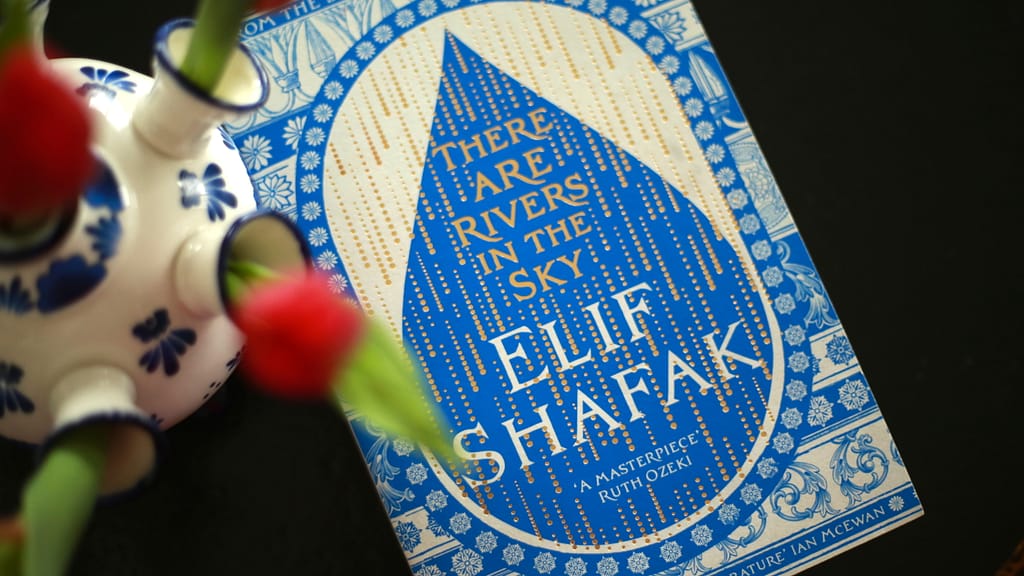

Elif Shafak’s There Are Rivers in the Sky: A Journey Through Time and Memory

A Mesopotamian sore spot that I’ve been dragging since middle school is the Epic of Gilgamesh. I don’t remember much besides the fact that I found it terribly boring and completely abstract, so I hoped I would never have to look at it again. If anyone had a chance of making me take on the subject once more, that would be Elif Shafak. And with her latest novel, There are Rivers in the Sky, she managed exactly that, without overwhelming me with the ancient poem, simply enticing my curiosity enough so that I find myself wanting to get back to the original text once more.

Elif Shafak is one of the few contemporary writers I’m reading almost religiously. I follow her literary activity, I rejoice whenever a new book is announced, and I’ve been lucky enough to hear her speak at the famous Parisian bookshop Shakespeare&Co a few years back. I find her presence to be soothing, much like her books, that open conversations about meaningful subjects, yet never leave you in the claws of despair.

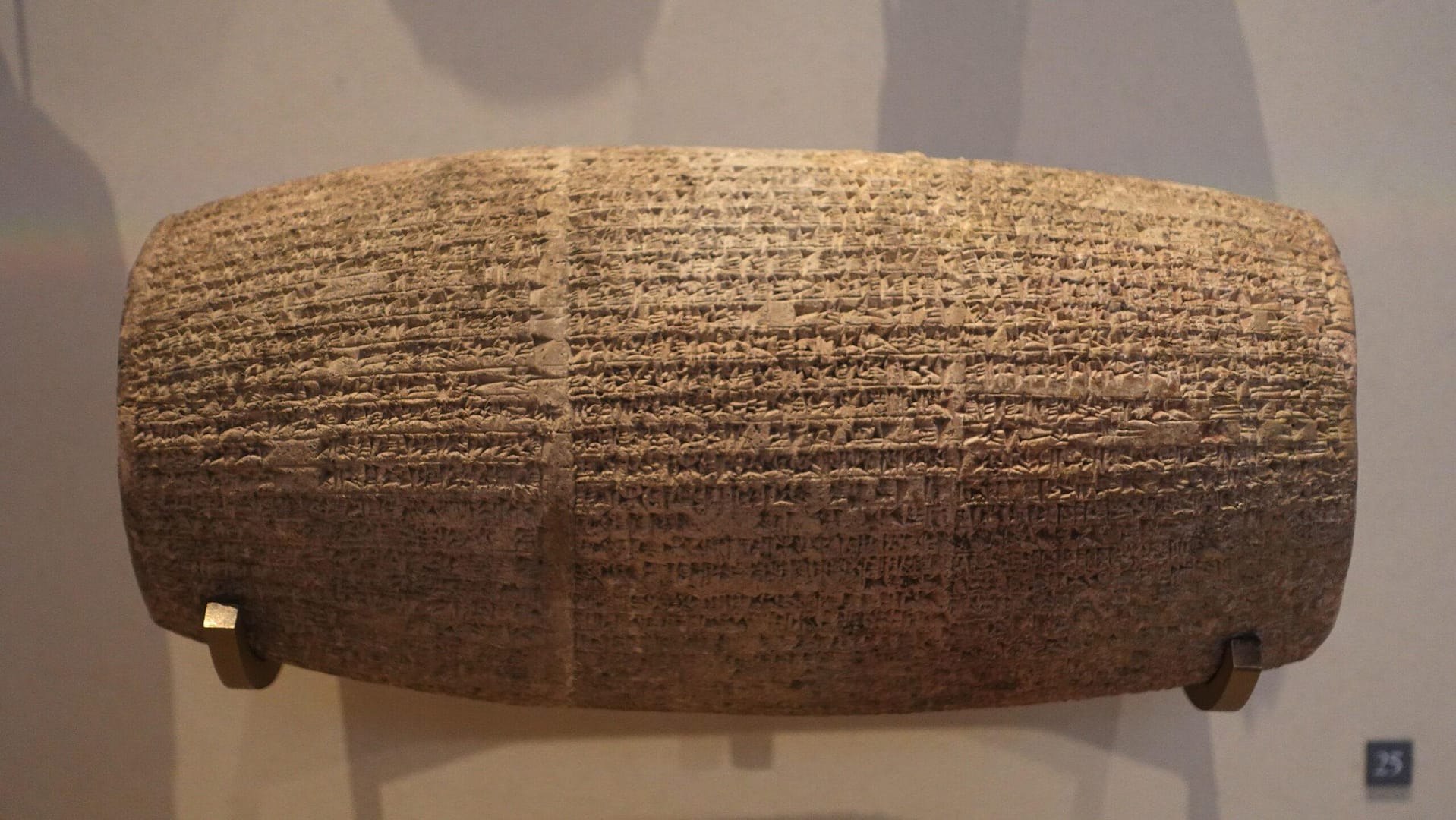

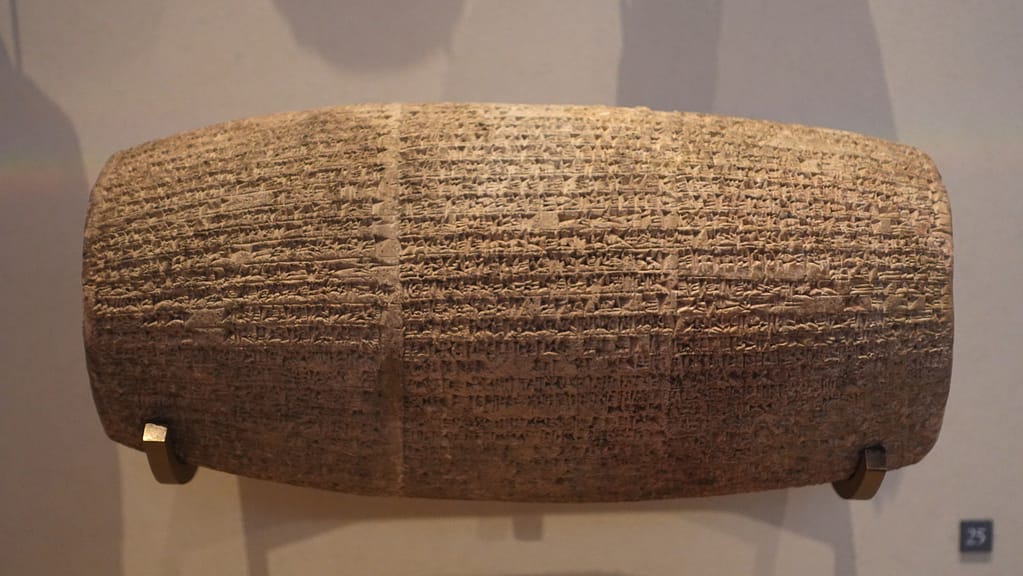

There are Rivers in the Sky tells three parallel stories, interconnected through symbols, history and a drop of water. Arthur, a boy born in the slums of 19th century London, whose only escape from poverty is his brilliant memory, is mesmerized by the ancient cuneiform tablets of King Ashurbanipal of Mesopotamia. Narin, a ten year old Yazidi girl living in 2014 Turkey, is diagnosed with a rare condition that will take away her hearing, so her grandmother faces the dangers of an ISIS infested region in order to take little Narin to the sacred baptism spot of the ancient Yazidi tribes. Zaleekhah is a newly divorced hydrologist living in 2018 London, where, after a youth spent as an orphan, and an unsuccessful marriage, she takes the decision to end her life in one month’s time, when an unexpected book gives her a reason to go on.

“A poem is a swallow in flight. You can watch it soar through the infinite sky, you can even feel the wind passing over its wings, but you can never catch it, let alone keep it in a cage. Poems belong to no one.”

– Elif Shafak, There are Rivers in the Sky

What is beautiful, and so specific to Shafak’s writing, is the blend of cultural and historic references with human stories that seem so close to our everyday life. Her love of the Middle East is rooted in the values of the many people that have shaped the history of this land. And through the destinies of these three characters, she gives a new perspective to stories that seem long forgotten. She’s not afraid to tackle the controversy surrounding the place of certain artefacts in Western Museums, she gives a voice both to those that struggle to survive in the harsh political climate of the Middle East today, and to those that have emigrated in search for freedom yet still carry the melancholy of their land. Her vision is far from black and white, and feels more like a dictionary that guides you, than an editorial as decisive as a judgment.

She often speaks of her characters as being the custodians of knowledge, the memory keepers, and I believe that these exact characters, be it in this novel or in others she has so beautifully crafted, are her guest appearance in disguise. Elif Shafak is the voice of communities, of minorities and of tribes that so many of us would have never known if it wasn’t for her writing. The vivid images she creates transcend the tragedies, and make the beauty of the Middle East remain engraved in our memories. Today, her Mesopotamia tastes of ripe fruit and salty tears, of bonds that never disappear and of freedom gained through courage. And in her words, the Epic of Gilgamesh gains an aura of mystery that I am curious to discover.

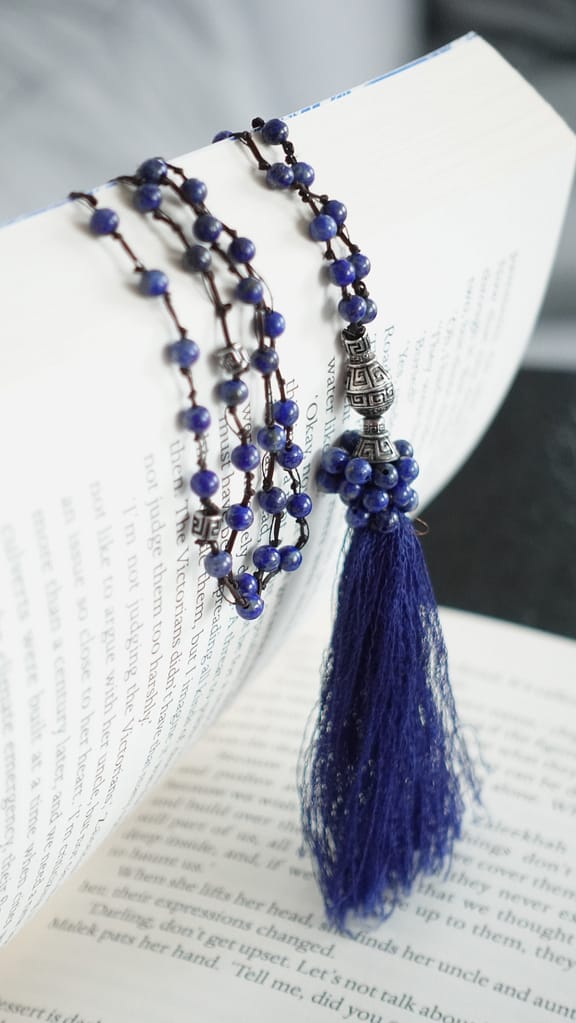

Lapis Lazuli: The Deep Blue of Mesopotamian Dreams

Mystery is a word that suits so many of the cultures that have inhabited ancient Mesopotamia, and is probably the most interesting gateway for me to explore the vastness that awaits. So while I’m reading Shafak’s novel, I’m connecting to one of the most enigmatic aspects of ancient Sumer, Akkad or Babylon : the symbolism of gemstones.

Regarded as esoteric superstition in today’s western culture, gemstones were directly linked to divinity in all of the ancient cultures. The Greeks held the amethyst in high regards, Roman soldiers wore onyx amulets for protection, the Egyptians believed the turquoise will guard their health, and the Chinese seeked harmony through jade. Many of them, however, held one particular gemstone as the true connection with the gods, and it so happens one of the earliest mentions of it comes from ancient Mesopotamia : the Lapis-Lazuli.

The Lapis is a dark blue metamorphic rock, which means that right from the beginning, its fate is something of a miracle. Imagine a common, unimpressive stone, the grey-brown pebble you don’t even notice anymore. And then, destiny strikes : our commoner gets subjected to extremely high temperatures, the pressure elevates to impressive values, and its chemical structure changes. The mesmerising minerals that compose it start to reveal themselves : lazurite, pyrite and calcite combine in an intricate pattern of dark blues spotted with speckles of gold, a thing of beauty. We can easily imagine why the Sumerian priests were always adorned with lapis beads when performing their rituals in front of the ziggurats : for them, this striking wonder of nature could only symbolize a tangible link between the earthly and the divine.

Today’s gemstone enthusiasts see Lapis-Lazuli as an enhancer for clarity of mind, which you might see as a re-interpretation of the divine connection observed in Antiquity. And while the therapeutic powers of being in contact with a gemstone are hard to prove, especially considering the placebo effect, I believe we should be looking farther than the cure of a headache or the soothing of an eczema when we think of well-being. Quantum physics seems to be the fashionable thing to mention when it comes to alternative therapies. But let’s not get confused by the noise around us : everything in the Universe is energy, and energy has a vibration.

That being said, where do I stand on lapis-lazuli ?

I’m currently wearing a long necklace of lapis-lazuli beads inspired by the meditation malas. It’s something I cherish dearly, since it’s custom made by my very best friend. Today however, I’m wearing it with a different intention, as a way of connecting with the little drop of Mesopotamian culture that I’ve been cultivating around me. Elif Shafak’s novel has a beautiful reference to the gemstone, that I’ll let you discover unspoiled, however my imagination carries me to the gemstone artists that worked with these stones every single day during the powerful rules of the most mythical Kings, transforming them into resplendent objects that would reflect the exceptional legacy of their culture. The Lapis vibrates around me with the energy of the eternal Mesopotamian wisdom, that has outlived its people, and, if we’re careful, will forever be a founding piece in the puzzle of humanity.

My Mesopotamian adventure is pausing here. I’m taking the time to savour the depth of Shafak’s story, until my next imaginary incursion into the land of the lamassu, and already planning my journey to Berlin, where I dream of seeing the deep Lapis blue of the Ishtar Gate kept in the Pergamon Museum.

I would love to know your thoughts on Elif Shafak’s novel and maybe your personal connection with the ancient Mesopotamian cultures. I’ll be keeping an eye on the comments.

Until next time, enjoy your reading, and your rituals !

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.

Shopping list

If you would like to support The Ritual of Reading, please consider purchasing your books from the Bookshop.org dedicated site by clicking the link below. You get to support local bookstores and I make a small commission with every purchase. Thank you !