Medieval Advent Calendar Day 8

Hello, dear friends, and welcome to today’s slice of medieval delights! You know by now my particular affection for cookbooks, since every Advent Calendar I’ve created has included at least one episode dedicated to them. My Scandinavian vegetarian Christmas book brought pure delight, and the Downton Abbey Christmas cookbook felt like a dream made tangible. But this year we have serious contenders for the top position, since the two cookbooks I’ve selected are genuinely remarkable—not merely for their recipes but for the windows they open into a vanished world.

The role of food in the construction and organization of human life stands without question as one of the most important factors in the development of our societies. In medieval times, food served much as it does today: both as a source of sustenance and as a means of expressing joy, marking celebration, demonstrating status, and creating community. While the upper classes enjoyed the luxury of importing ingredients from the East—spices worth their weight in gold, exotic fruits, rare delicacies—the majority of the population lived and ate according to the strict rhythm of seasons, relying on what the land provided in each month’s turn.

In Europe we often speak casually of vegetables considered staples in contemporary cuisine that were not yet known in the Middle Ages, or mention that people ate with spoons alone since the fork wasn’t introduced until considerably later. But let’s consider this more concretely: your classic peasant’s stew, essential for warming and filling the bellies of an entire family through the long winter, would contain no potatoes, no tomatoes, no peppers, and no corn—all of these were brought to the Old World only after the great expeditions of the Renaissance into what Europeans called the New World. You were left, then, with cereals (primarily wheat, barley, rye, and oats), various cabbages, root vegetables like turnips and parsnips, pulses such as beans and lentils, and occasionally venison or domestic meats when fortune allowed.

The question becomes: what could you create with these limited ingredients? How did medieval cooks transform constraint into cuisine, scarcity into satisfaction? Let’s discover what they accomplished.

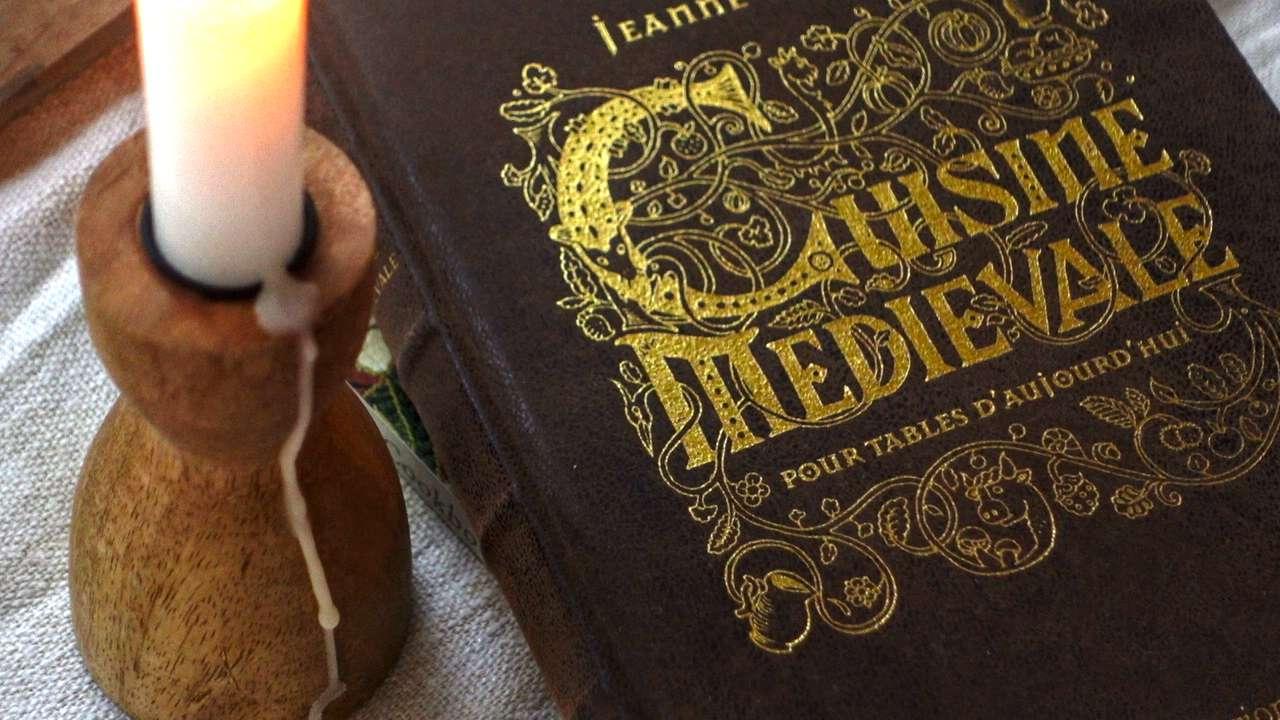

Cuisine Médiévale pour Tables d’Aujourd’hui

(Medieval Cuisine for Today’s Tables)

by Jeanne Bourin

Jeanne Bourin, a historical novelist with profound passion for the Middle Ages, dedicated an entire book to the gastronomic research she conducted throughout her writing career. Medieval Cuisine for Today’s Tables gathers 160 recipes, all of which have been carefully quantified, developed, and adapted to contemporary tastes and modern kitchen realities, while preserving the original Old French recipe as an introduction to each entry. This parallel presentation is invaluable—you see both the historical source and its practical modern translation, understanding what has changed and what remains constant.

Her translation operated on words and ingredients alike. The recipes contain fewer spices than medieval originals (which used astonishing quantities we’d find overwhelming today), and preparation times have been significantly reduced to suit our accelerated lives. Yet the essential character of each dish remains intact—you’re tasting something recognizably medieval, not merely a modern dish with a historical name attached.

Crucially, this is not the cuisine of lords and ladies that Bourin offers us, but that of ordinary inhabitants of cities and villages—the people who formed the vast majority of medieval society. No sumptuous multi-course feasts designed to display wealth and impress rivals, but rather good, honest recipes for soups that nourished families, preparations for poultry and game, methods for cooking fish (so important given religious fasting requirements), pastries both savory and sweet, and various drinks from the prosaic to the festive.

By recreating the atmosphere of everyday medieval meals and bringing the gastronomic habits of centuries past to contemporary tables, Medieval Cuisine for Today’s Tables breathes new life into our modern cooking. It reminds us that people have always sought pleasure in eating, have always worked creatively with available ingredients, have always gathered around tables to share not just food but fellowship. We’re not so different from them, really—we’ve simply forgotten some of what they knew.

The Medieval Cookbook

by Maggie Black (British Museum Press)

On the English side of the Channel, The British Museum Press entrusted food historian Maggie Black with creating a medieval cookbook drawn from fourteenth- and fifteenth-century English sources. Including references to works by Geoffrey Chaucer—whose pilgrims in The Canterbury Tales certainly ate and drank their way to Canterbury—and carefully adapted to suit modern kitchens, this beautifully illustrated volume explores the traditions and tastes of authentic medieval cookery in English lands.

This is a mouth-watering collection inspired by medieval manuscripts, covering the period from the fall of the Roman Empire through Henry VIII’s break with Rome in the 1530s—essentially the entire span of what we call the Middle Ages in England. While considering the complex relationship between food and religion (with its meatless fast days, fish Fridays, and elaborate rules around Lent), and examining the stark differences between the diets of rich and poor, this book provides a remarkably diverse selection of recipes that capture the true essence of dining across medieval society.

What distinguishes this cookbook is its visual richness. Illustrated throughout with stunning scenes of food, feasting, and cooking drawn from period paintings, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, and drawings, the book becomes a valuable mirror of medieval society viewed from the table. You see how food was served, how people ate, what dishes looked like, how kitchens functioned, how celebrations unfolded. The recipes exist within rich visual context that helps modern readers understand not just what people ate but how they experienced eating.

The recipes themselves range from simple pottages (thick vegetable soups) to elaborate subtleties (decorative dishes meant to amaze and entertain), from everyday bread to feast-day pastries, from fish preparations designed to satisfy both hunger and religious obligation to roasted meats that signaled celebration and prosperity. Each recipe carries historical annotation explaining its social context, its ingredients’ availability and cost, its place in the medieval culinary hierarchy.

These are cookbooks to have and to cherish, to consult whenever inspiration is needed or simply to browse through as a form of time travel that requires no special equipment beyond imagination and appetite. They remind us that cooking connects us across centuries—that the medieval cook trying to make turnips interesting for yet another winter meal, or attempting to impress guests with limited resources, or simply feeding a hungry family at day’s end, shares fundamental experiences with us despite the vast gulfs of time and technology that separate our worlds.

The recipes work. The flavors surprise. And suddenly the Middle Ages feel less like a distant, incomprehensible era and more like a time inhabited by people recognizably human, who loved good food just as we do, who took pride in cooking well, who understood that a well-prepared meal offers not just nutrition but comfort, pleasure, and a kind of everyday magic.

Until tomorrow, dear friends—may your medieval culinary experiments be delicious, and may they connect you to the long chain of cooks who came before us, all trying to create something beautiful and nourishing from whatever ingredients came to hand.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.