Medieval Advent Calendar Day 7

Welcome back, dear friends! I hope you’re wearing sturdy boots, because today we’re walking. After meeting Eleanor and tracing the arc of her extraordinary life, I wanted to visit the only place still standing in Paris that she would have known during her years as Queen of France. That place is the Conciergerie.

So off we go to the Île de la Cité, that great island in the middle of the Seine, to explore what remains of the Palais de la Cité—the royal palace of French kings beginning with Clovis in 508 and continuing until Charles V in the late fourteenth century, when he decided to relocate the court to the Louvre.

The palace underwent many transformations over its long history, and the oldest sections visible today were actually built about a century after Eleanor’s death. Yet these are the walls she inhabited during the fourteen-odd years she spent as Queen of France, from her marriage to Louis VII in 1137 until their annulment in 1152. To stand here is to occupy the same space she once moved through—to breathe air in rooms where she breathed, however changed they may be.

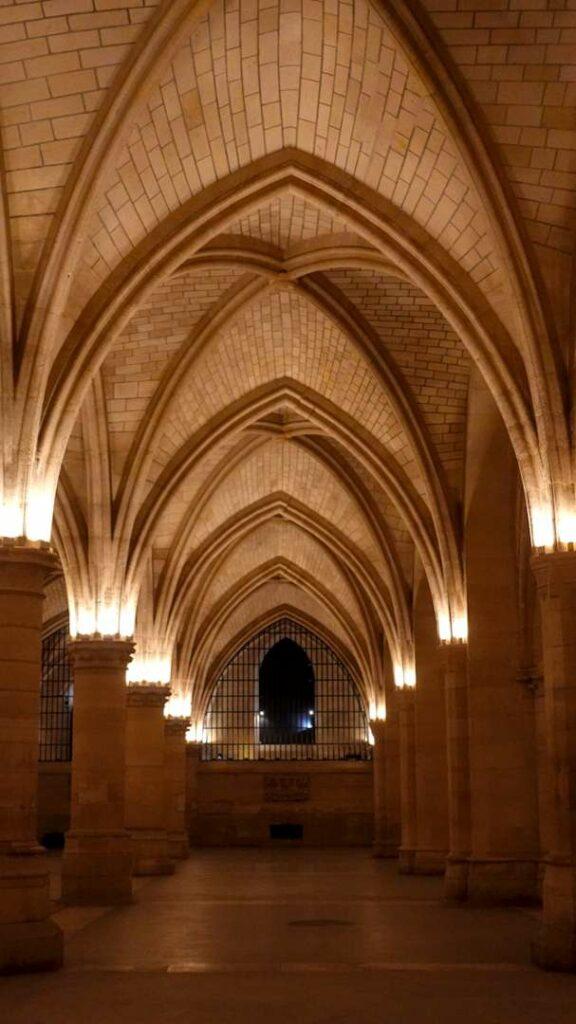

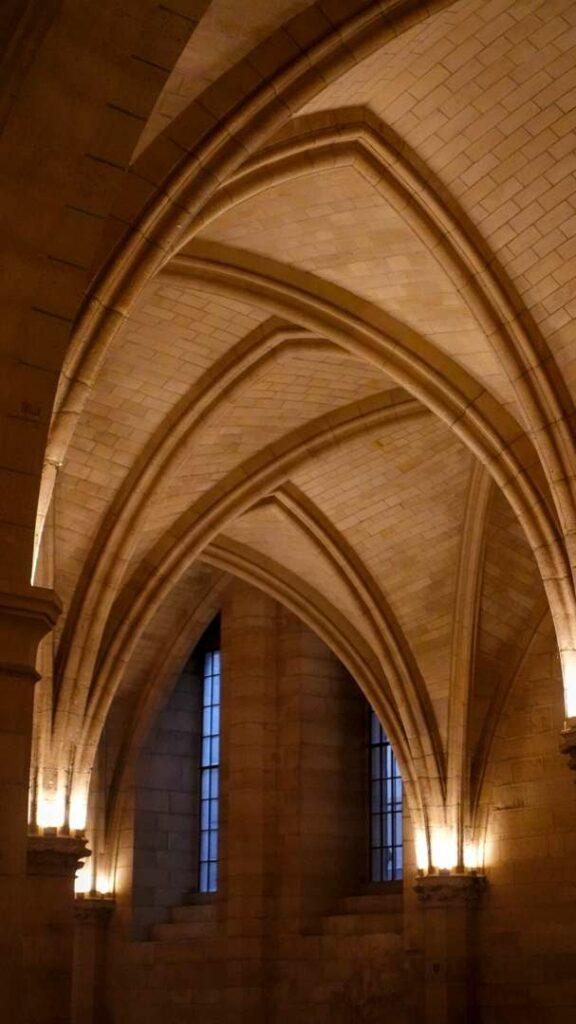

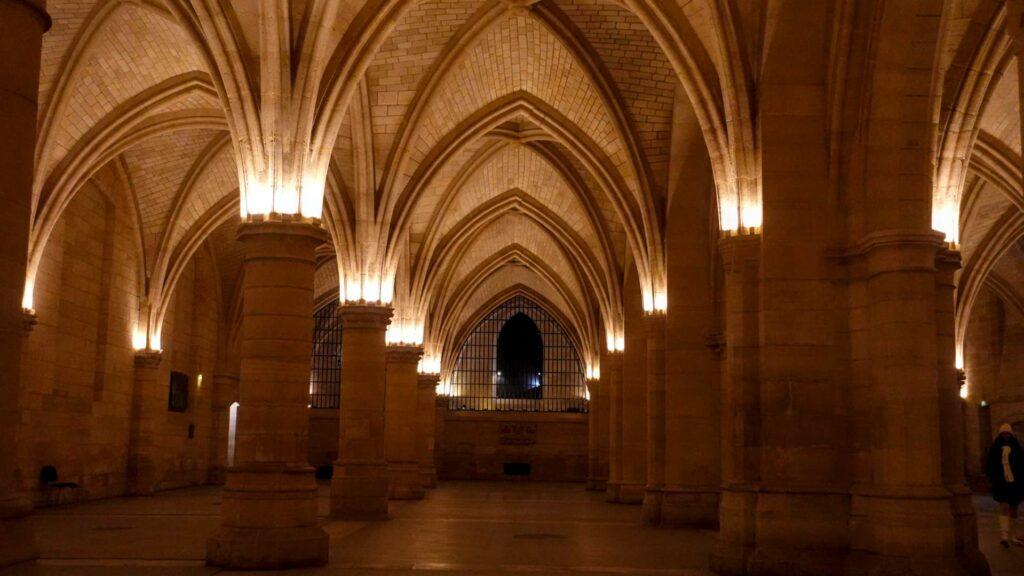

The most impressive surviving space is the Hall of the Men-at-Arms, constructed in the early fourteenth century as a dining hall and gathering place for the guards and servants who worked in the palace—anywhere between one and two thousand souls at the height of the court’s activity. The forest of pillars supporting its vaulted ceiling makes it difficult for the untrained eye to grasp the hall’s true scale, but this is the largest Gothic secular hall in all of Europe. The term “secular” matters here: most surviving medieval spaces of this grandeur are religious—cathedrals, abbey churches, chapter houses. Secular great halls rarely endured.

For me, medieval constructions possess a mystical dimension hidden beneath the austerity of their appearance. Looking at these masterpieces of structural engineering that have withstood seven hundred years (an impressive span by any measure), I think of the master masons who selected each stone with exacting care to match plans engraved in their imagination and experience. I see the rumble and chaos of Christmas Eve dinners, servants rushing to ensure everything was perfect upstairs in the royal apartments. I hear the solitary footsteps of the night guard coming to fetch a cup of wine in the dead of winter darkness. A whole world contained in a story told by stone and space and the ghosts of countless ordinary days.

There is one more artifact Eleanor would have known, though it no longer resides in the heart of Paris. Her first husband, King Louis VII, was an exceptionally pious man—some would say obsessive in matters of the Church, which created considerable tension in a marriage to someone as worldly and politically astute as Eleanor. His closest ally and confessor was Abbot Suger, who served as Louis’s principal minister and counselor and was also the visionary architect behind the Basilica of Saint-Denis, regarded as the birthplace of Gothic architecture.

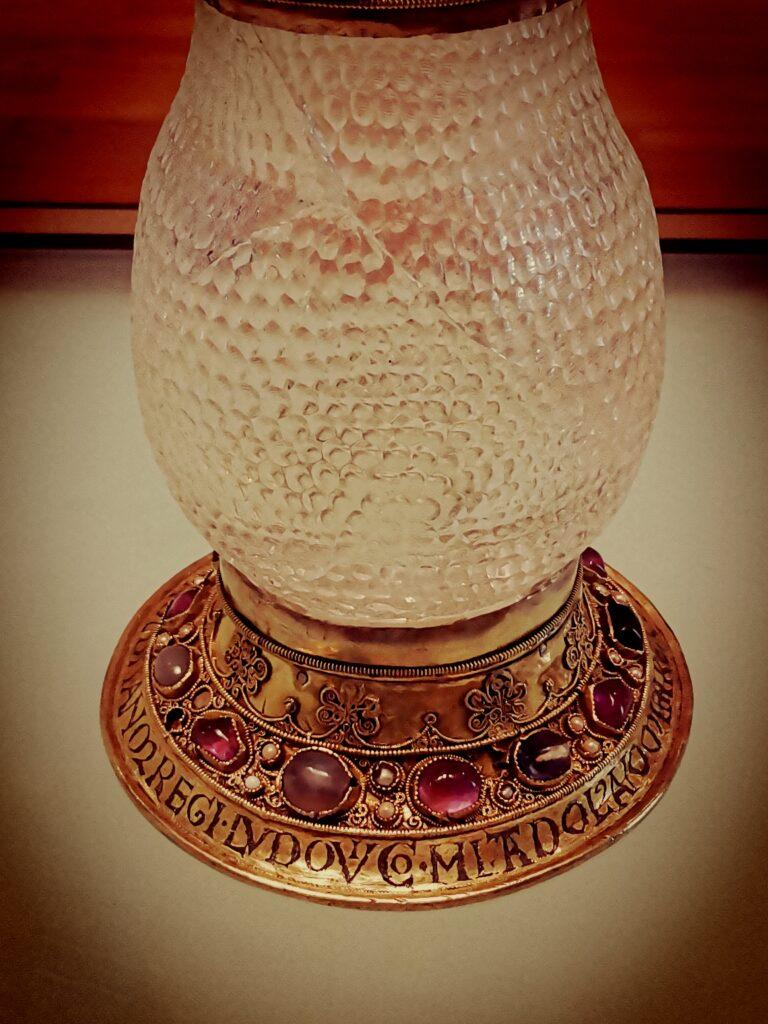

Suger assembled during his lifetime an extraordinary treasury for Saint-Denis, naturally with considerable help from the king. One of the most notable donations Louis VII made to Suger for safekeeping was a gift he himself had received on his wedding day from Eleanor: a clear rock crystal vase with an intricate honeycombed pattern, thought to be of Persian origin. Suger enriched this already precious object with a golden-silver mount studded with gems, transforming it into something even more magnificent.

On its base, a Latin inscription tells its story in compressed form: “This vase, Eleanor his wife offered to King Louis, Mitadolus to her grandfather, the king to me, and Suger to the Saints.” Each phrase traces one link in the chain of possession and devotion.

Mitadolus was the Latinized name of Imad al-Dawla Abdelmalik, the Muslim king of Zaragoza, who presented the vase to Eleanor’s grandfather, William IX of Aquitaine—yes, the troubadour—as a token of gratitude for his military assistance against the Almoravids. Despite the violence and religious antagonism of the Crusades, the Islamic world remained an inexhaustible source of fascination for European intellectuals, particularly in matters of art, science, and craftsmanship. This vase was regarded as one of Eleanor’s most prized possessions, which made it the perfect declaration of esteem, commitment, and trust to offer her future husband on their wedding day.

Today it resides in the Louvre among many treasures once held by Suger at Saint-Denis, which renders it both accessible and mysterious. An object that began as mineral matter deep in the earth, shaped by a Persian craftsman into functional beauty, passed through Eleanor’s hands as inheritance and then gift, was preserved for centuries as an offering to the saints, and now stands before us behind museum glass. It’s somewhat miraculous when you consider it—this chain of preservation across nearly nine hundred years, through revolutions and wars and the simple erosion of time.

To look at it is to touch, however distantly, the woman who once held it.

Until tomorrow, dear friends—happy Advent, and may your wanderings lead you to unexpected connections with the past.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.