Medieval Advent Calendar Day 5

Hello, dear friends, and welcome to our fifth day of Advent, where things become decidedly merry. One of the most celebrated legacies of the Middle Ages is the tradition of the troubadours, and it happens that this subject connects directly to Eleanor of Aquitaine. So without further ceremony: welcome to the banquet!

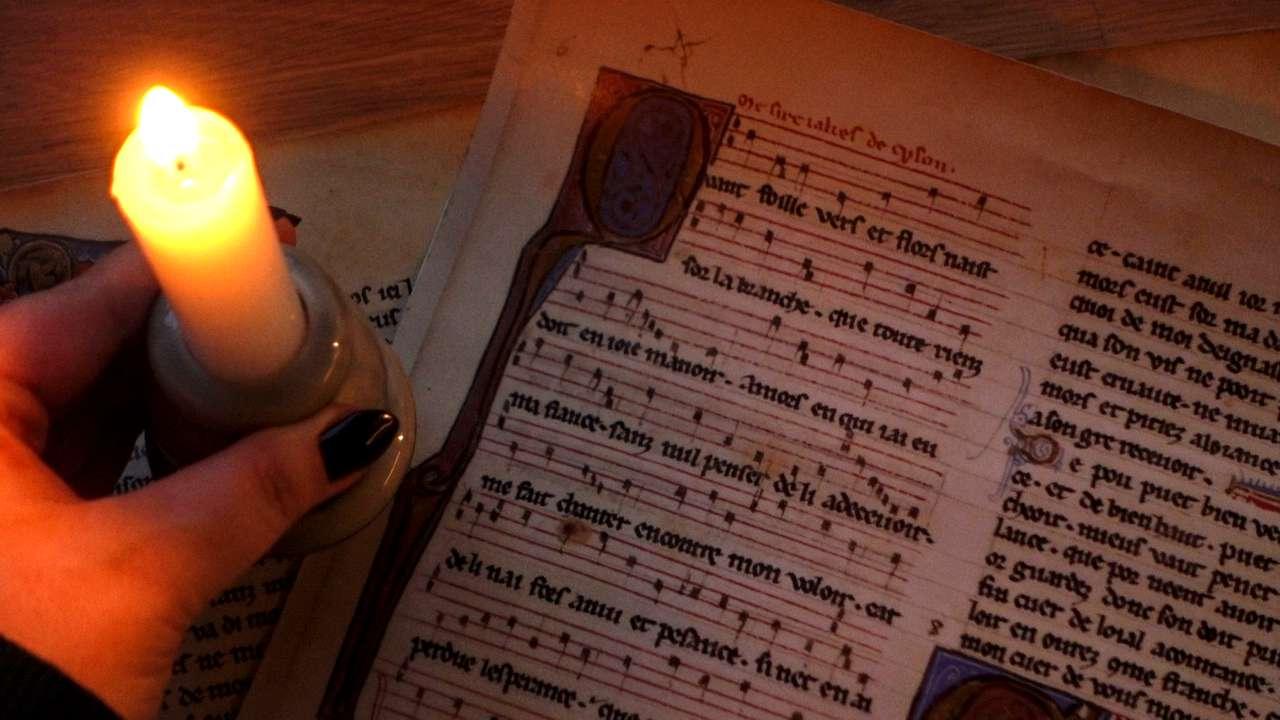

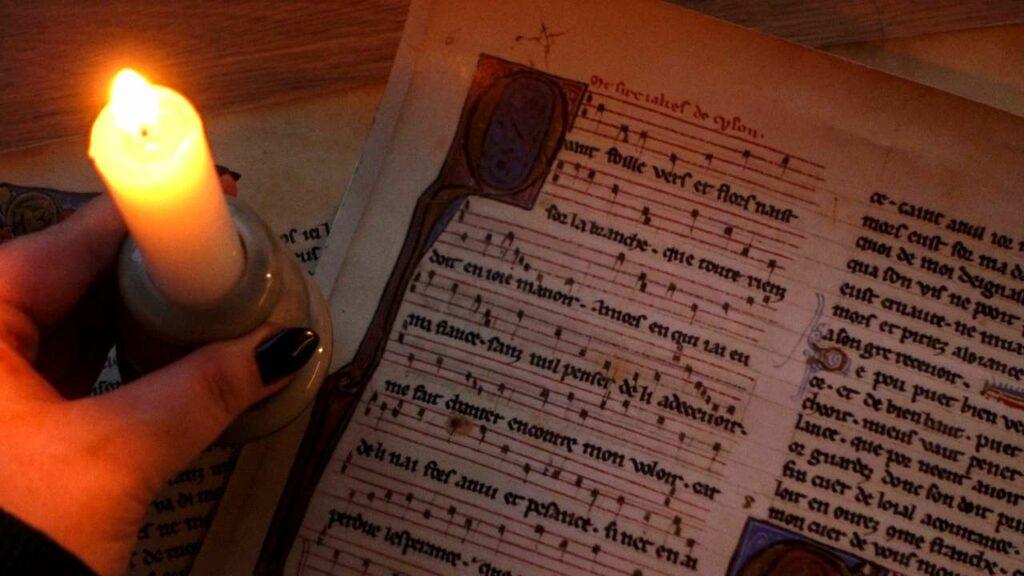

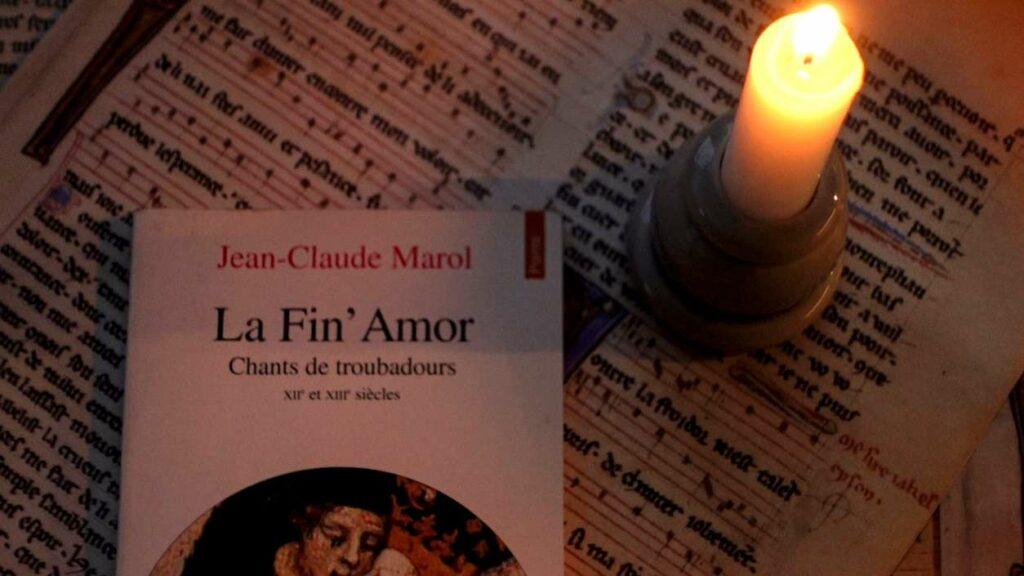

Troubadours were composers and performers of lyrical poetry in the Occitan language during the High Middle Ages, primarily in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. A brief linguistic reminder: the territory we now call France was divided in medieval times into two distinct regions based on their word for “yes.” The langue d’oc was spoken in the southern territories, also known as Occitanie, while the langue d’oïl dominated the North, with the Loire River serving roughly as the dividing line between them.

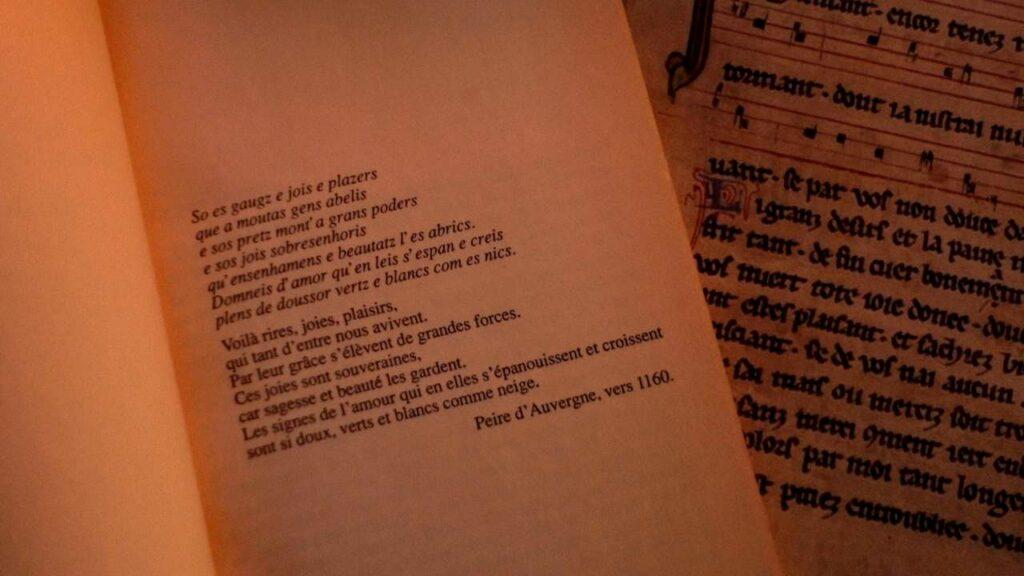

Language shapes cultural tradition profoundly, and so it was that the troubadours—with the song of their particular words and the warmth of the Mediterranean in their blood—created an art of lyrical poetry in Occitan to celebrate chivalry and courtly love. Their northern equivalents were the trouvères, who composed in the langue d’oïl. Among the earliest and most famous was Chrétien de Troyes, of whom we shall speak more later in our Advent journey.

The earliest troubadour whose work survives to this day was Duke William IX of Aquitaine—none other than Eleanor’s grandfather, the one whose Persian crystal vase we encountered at the Louvre. The fact that a powerful nobleman devoted considerable time to composing poetry and performing it himself reflects the extraordinarily high esteem accorded to troubadours during this period. The art of sublimating life’s events into refined verse was, perhaps even more than now, considered a noble and respected occupation. This cultural context explains why troubadours held such an important place throughout Eleanor’s life. She brought them with her to Paris when she became Queen of France, surrounding herself with the sophisticated southern culture she’d grown up with. Later in life, she enjoyed their company so openly that rumors arose suggesting inappropriate relationships between artist and muse—rumors that tell us as much about courtly culture as about Eleanor herself.

Troubadours were essential presences at every great feast celebrated by lords and ladies, appearing alongside other, less artistic entertainment provided by minstrels: buffoons, jugglers, acrobats, even fakirs. This gave them opportunities to observe and document local customs, including culinary traditions. William IX himself provides our earliest literary attestation of capons served as delicacies at noble tables—birds that remain traditional Christmas fare in many regions of France today. He writes with characteristic directness:

They fed me capons,

And know that I had more than two;

And there was neither cook nor cooks,

But the three of us;

The bread was white, the wine was good

And the pepper was plenty.

There’s something wonderfully immediate about these lines—you can almost taste that white bread, that good wine, that generous pepper. Poetry as sensory memory, pleasure recorded and transmitted across centuries.

Entertainment became especially important during Advent and the twelve days of Christmas that followed. Theatrical representations were performed in front of churches—liturgical dramas at first, then gradually evolving into narrative performances adapted from biblical stories or saints’ lives. Although troubadours aren’t specifically documented at Christmas celebrations, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to imagine them at the center of such festivities. They represented an ideal of beauty and refinement that was desperately needed during a period we often romanticize but which was, in truth, frequently harsh and uncertain.

Like all art forms that survive the passage of time, troubadours serve as ambassadors of a world that tends to fade from our collective memory. They remind us that people in every era have sought beauty, have tried to capture feeling in form, have wanted to transform the ordinary into something worth remembering. Their poetry—celebrating love both spiritual and earthly, praising valor and lamenting loss, finding joy in bread and wine and pepper—connects us to the fundamental continuity of human experience.

Let us sing, then, and remember them for the joy they brought into a world that needed it as much as ours does now.

Until tomorrow, dear friends—may your feasting be abundant and your entertainment delightful.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.