Hello everyone, and Merry Advent ! If I haven’t lost you yet, through the maze of Kings and knights, palaces and cups of sage wine, then today might be the day. But hang tight, we’ll get through this together.

When it comes to reading the classics, no matter the period or genre, there is a certain apprehension that blocks most of us. Will this be tedious and complicated ? Will I enjoy a story so distant from my reality ? and will the language be within my reach ? But what would a medieval literary Advent Calendar be without the two pillars of French and English literature of the time ? Let’s give this a try.

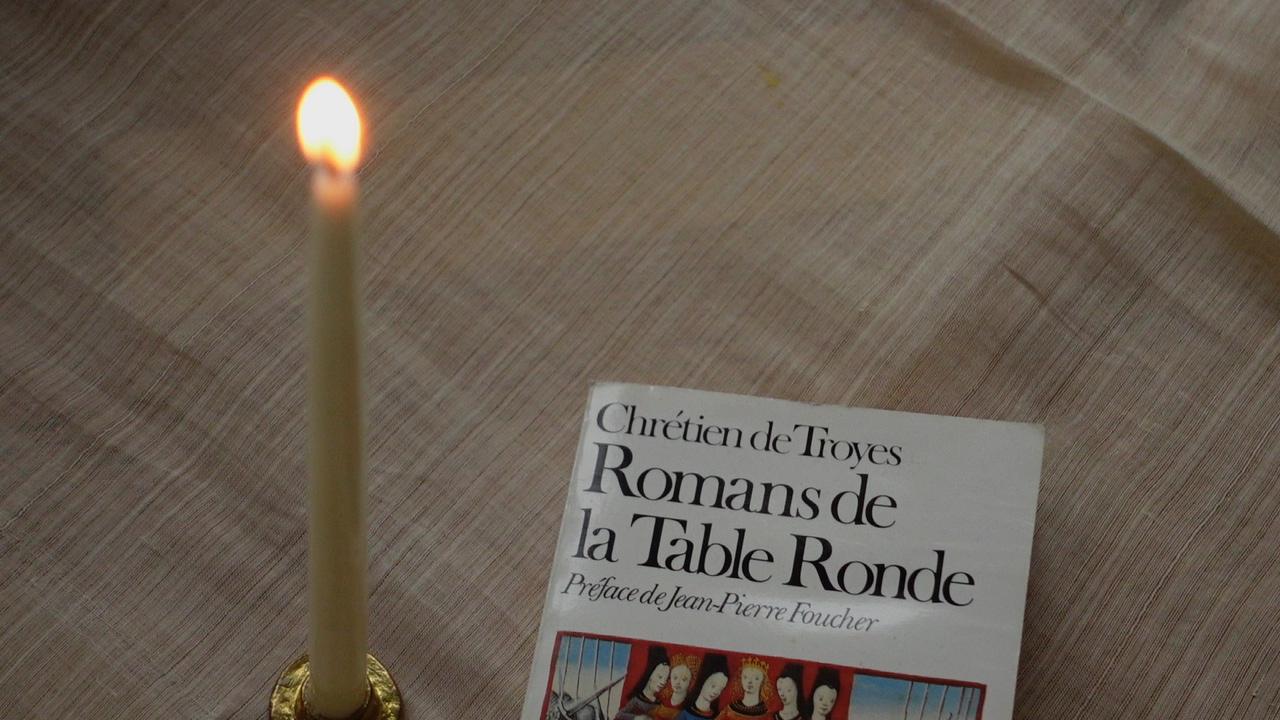

Chrétien de Troyes was a French poet and trouvère of the XIIth century, who lived in Champagne, then a vassal state of the Kingdom of France. Champagne was one of the richest and strongest of the French principalities during the reign of Henry I, count of Champagne. Chrétien served at his court and was devoted to his wife, Marie of France, daughter of Louis VII of France and, you’ve guessed it, Aliénor of Aquitaine. Marie was one of the two daughters from Aliénor’s first marriage.

Chrétien de Troyes is best known for his writing on Arthurian subjects such as Lancelot, Perceval and the Holy Grail, in chivalric romances that represent some of the best-regarded works of medieval literature. The original manuscripts are in Old French, I don’t recommend them to anyone, but the translations are quite atmospheric. I studied them a long time ago, during my first year of Uni, and in all honesty, I’m more prepared to face them now, than I was back then. The descriptions create an authentic medieval frame for characters that give such a vast understanding of moral values in XIIth century France. Valiant knights, honorable kings, delicate ladies with iron willpower, and of course, the wise conclusions of the poet :

“A good silence never harmed anyone but speaking often causes harm.”

Fast forward two centuries later, and crossing the Narrow Seas, we meet English poet, author, and civil servant, Geoffrey Chaucer. Often called “the father of English literature”, Chaucer symbolises the official linguistic emancipation of English literature from the Anglo-Norman French, to Middle English. It’s funny to think two countries who’re not famous for their mutual love through history, have shared a language for centuries.

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales are one of my literary mountains to climb, the reference you hear of even when you’re not a native English speaker, and which seems to test your limits of the language. Twenty-four tales presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims, as they travel together from London to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket. The frame is set, I can find my bearings. The language, on the other hand, swings between delight and total confusion. I’m still reading it as we speak, so all I can offer are ongoing impressions.

The stories written in verse have the most charm to them, in my opinion, since they fit my idea of the medieval tale contest, and also elevate the general impression of early literature as being rudimentary. Since I’m combining the written and the audio book, the song of the verses becomes almost hypnotic. I confess I’m having trouble following the stories, so I often go back, re-read, pause. This is one of the most challenging reads I’ve had in years, but strangely enough I’m quite enjoying it. I feel like one of the gang, maybe a child trotting along and trying to understand what my travel companions recount of social conflicts and religious authority. It definitely succeeds in transporting me to the Middle Ages, and that’s absolutely perfect for now, although I must keep in mind Chaucer’s words :

“people can die of mere imagination”

Until tomorrow, Merry Advent !