A cruise on the canals of Amsterdam… You get to marvel at the architecture, to admire the vision of a nation that has built a legacy for centuries to come, and without even knowing it, you experience a small part of what daily life was like for some of the most famous Dutch men in the world. Rembrandt, Vermeer and Van Gogh need no introduction. And while they don’t all have an equal connection to the city of Amsterdam, you do get a sense of their cultural background and inspiration when strolling along the canals. Just as with my previous Dutch inspired video, I have read the books I’m about to talk about in preparation for my trip, and they have made such a difference. All that I have seen has been a coming to life of the extraordinary things I read about. So grab yourself a cup of coffee, or a more authentic Amsterdammer pint, and join me for an immersion into Dutch painting through books.

The Anatomy Lesson, by Nina Siegal

We start off in 1606, the birth year of Rembrandt van Rijn. While born in Leiden as the second child of a miller, it is in Amsterdam that Rembrandt became the great master of the clair-obscur, and it all started with a rather bold subject, in the 1632 canvas called The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

Nina Siegal’s novel The Anatomy Lesson tells the story of the 24 hours that saw the hanging of a man, his becoming a subject for the annual anatomy lesson of the surgeons guild, and the creative process of Rembrandt as he went about painting his first masterpiece. The chapters alternate the perspective of different characters that played a role in the event, from the hanged man and his sweetheart, to the doctor, the curio dealer, René Descartes or Rembrandt himself : this feels very much like a theater play, with characters approaching the spectators one by one, as they give away another little piece of the puzzle.

Just as the event itself meant so much for the understanding of the world in the 17th century, the presence of Rembrandt and his visionary approach on the lesson in Nina Siegal’s words give us a first glimpse into the remarquable personality of the master.

“There is nothing dirty about the anatomy. I love the anatomy; it is my birthright, my legacy, my very parentage. I love its ceremony and its pomp; I love the doctor’s feigned authority and the spectators’ awe and civility. But amid all the bloodletting, cutting, lecturing, banqueting, torch-lighting, and debauchery, the scientists […] are doing something important. Like the Egyptians before them, they are building the foundations of a civilization.”

― Nina Siegal, The Anatomy Lesson

Rembrandt’s Mirror, by Kim Devereux

Rembrandt’s love life seems to be of great interest to out modern day curiosities. Historians and writers alike have delved into the passions of the three women who seem to have left a mark on the painter’s life in its different stages : his wife, Saskia, the nanny of his son, Geertje, and Hendrickje the housemaid.

Kim Devereux’ novel, Rembrandt’s Mirror, starts off at the death of his wife Saskia, then tells the story of Rembrandt’s grief and slow return to life thanks to the presence of Geertje, and finally his falling in love with the last women to have won his heart, Hendrickje. Of the three novels I read, this one is the most historically accurate and therefore gives the best idea of Rembrandt’s life in Amsterdam. Visiting his old house turned into a museum on the canals, I recognised many of the details in the book, from the boxed beds to the kitchen sink and the attic workshop flooded with light.

Probably his most famous canvas, The Night Watch has been painted around the time of his wife’s death. One of the central attractions of the Rijksmusem, the painting has many secrets yet to uncover, as a team of experts is studying the best way to preserve it for the future. You can follow along and read the latest findings on the museums website, under Operation Night Watch.

“His brush hopped from palette to canvas, like a songbird after a worm, applying paint to a golden sleeve. Then he did something I’d never seen him do before – he turned the brush on its end and stabbed the wooden handle deftly into a bowl of discarded, dried-up paint, scooping some up and mixing the paint crumbs with some yellow and ochre. Then he took the palette knife and applied the thick mixture to the canvas, sculpting the sleeve more than painting it. Even from the doorway I could see it rise into being. A miracle; not that he had rendered gold brocade from old paint, but that he’d invented something new with the same casualness with which I drank from a glass of water.

It was the essence of how he worked. The hundreds of thousands of strokes he’d made before had no bearing on this stroke, other than his manual skill. He was guided only by what was to be achieved in painting the sleeve – for this crest of paint to catch the light. He was perfectly free in this. If only I could be too.

I continued to watch him paint. It was like a tonic.

The sleeve was all there now. He’d turned waste into gold.”

― Kim Devereux, Rembrandt’s Mirror

The Painter, by Will Davenport

The most whimsical of the three novels I read, was Will Davenport’s The Painter. Rembrandt is famous for never having left the Netherlands, especially in a time when all the painters were travelling to Italy in order to learn the technique of Caravaggio. So when a writer imagines a secret boat ride to the English city of Hull, where Rembrandt would have bought his ticket back home by painting two portraits, you’re in for a relaxing read. The plot moves between the 17th century and the present day, where a team of builders and restorers happen to come across a few sketches and old letters that suggest this improbable story. The tension is gradually built so that you can hardly put the book down once you’ve started. And from Will Davenport’s research on the painter, there are many passages that reveal glimpses of his character and of his intimate thoughts.

One of the subjects of great interest from his prolific career, has been the multitude of self portraits he painted. Many theories have been formulated, each with its own fragment of the truth, but I especially enjoyed Davenport’s take on the subject :

“Why do I paint my face ? There’s a quick answer I usually give. Nobody else keeps still enough for long enough, and I don’t have to pay myself. There’s a less pat version I have sometimes given when I particularly want to impress someone. It is that I know what’s behind those eyes. I know exactly how the restless consciousness inside moves that flesh-mask and therefore I face a more subtle task when I paint myself than when I paint any other.

Then there’s the real reason, the one I don’t admit to anybody, and hardly ever even to myself. The other reasons are true enough so far as they go but the main reason I do it is that it makes me feel better. When I’m feeling the pinch, when I wake up at first light and the pressure of my debts hits me in the face, it is a relief to start touching in the highlights of the gold chain around my neck. When I start to worry that in another few years the folds on my face will be taken for age, not character, then I can look at the evidence that my paintbrush has produced to reassure myself that the bull is still a bull and all the better for a bit of character.”

― Will Davenport, The Painter

Girl with a pearl earring, by Tracy Chevalier

From one legend to another, we meet in 1632, the year of birth for Johannes Vermeer. Modestly famous during his lifetime, Vermeer became better known in the 19th century before turning into a global phenomenon. His domestic interior scenes, with their famously careful lighting and elegant chromatic, have fascinated art lovers for generations.

When Tracy Chevalier decided to write her bestselling novel Girl with a Pearl Earring, nobody could have suspected the global reach it would have, especially once it was turned into a movie. The novel, however, has a much more intimate feel, and the unmistakable charm of Chevalier’s style. I remember reading it 20 years ago. It was one of the first historical fiction novels I dipped my toes in, and I was in awe at how easily you could explain historical facts or details of a craft by putting them into context. Even today, after all the hype around the book and the movie, I still think this could be the book that sparks an interest for art or for history in the younger generation.

“There is a difference between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to painting,” he explained as he worked, “but it is not necessarily as great as you may think. Paintings may serve a spiritual purpose for Catholics, but remember too that Protestants see God everywhere, in everything. By painting everyday things-tables and chairs, bowls and pitchers, soldiers and maids-are they not celebrating God’s creation as well?”

― Tracy Chevalier, Girl with a Pearl Earring

Girl in Hyacinth Blue, by Susan Vreeland

After the strong impression that Tracy Chevalier’s book had left on me, I didn’t think any other writer could present Vermeer to me in an equally fascinating way. And then, I came across Girl in Hyacinth Blue by Susan Vreeland.

Take an imaginary secret painting of Vermeer’s and cross the centuries along with it, from Delft in the 1600, to modern day United States. You see history unravel, you hear the world change as the paint dries into place, and then, when you finally close the book, you’re left with an urge to step into a museum and discover its secrets.

Susan Vreeland’s novel has been one of the great surprises of my Spring reading. It made me think of the lesser know yet not less important hyacinth fever, that preceded the golden years of the tulip in the Netherlands, and of course, it put the spotlight on the signature colour of Johannes Vermeer’s art :

“Pulverizing a small brick of ultramarine with a mortar and pestle one day, loving the intensity of blue as rich as powdered lapis lazuli, he heard a commotion in the main room. His second daughter, Magdalena. Far too old for this. […] There was something in this girl he could never grasp, an inner life inscrutable to him. He was in awe of the child’s flights of fancy, her insatiable passion always to be running off somewhere, her active inner life. To still it for a moment, long enough to paint, for eternity, ah.

Was it possible to pain with good conscience what he didn’t understand ? What he didn’t even know ?

“Sit down.”

Painting was the only way even to attempt to know it.”

― Susan Vreeland, Girl in Hyacinth Blue

Lust for life, by Irving Stone

From two Baroque masters, we jump two centuries forward, to meet the rebel, the misunderstood, the free yet captive Vincent Van Gogh.

His unique personality has inspired many writers, but I believe Irving Stone’s take on Van Gogh in his novel Lust for Life is one of the most complete. I first read it about ten years ago, and what remained with me was the Dutch period in his life, such poignant descriptions of the places and mostly the people, images I recognised in his famous Potato eaters. Irving Stone has managed to bring forward the emotion in Van Gogh’s life, more than the drama or the impulsiveness of his temper, you get to live in the artist’s mind for a short while, and understand his quest.

“I cannot draw a human figure if I don’t know the order of his bones, muscles or tendons. Same is that I cannot draw a human face if I don’t know what’s going on his mind and heart. In order to paint life one must understand not only anatomy, but what people feel and think about the world they live in. The painter who knows his own craft and nothing else will turn out to be a very superficial artist.”

― Irving Stone, Lust for Life

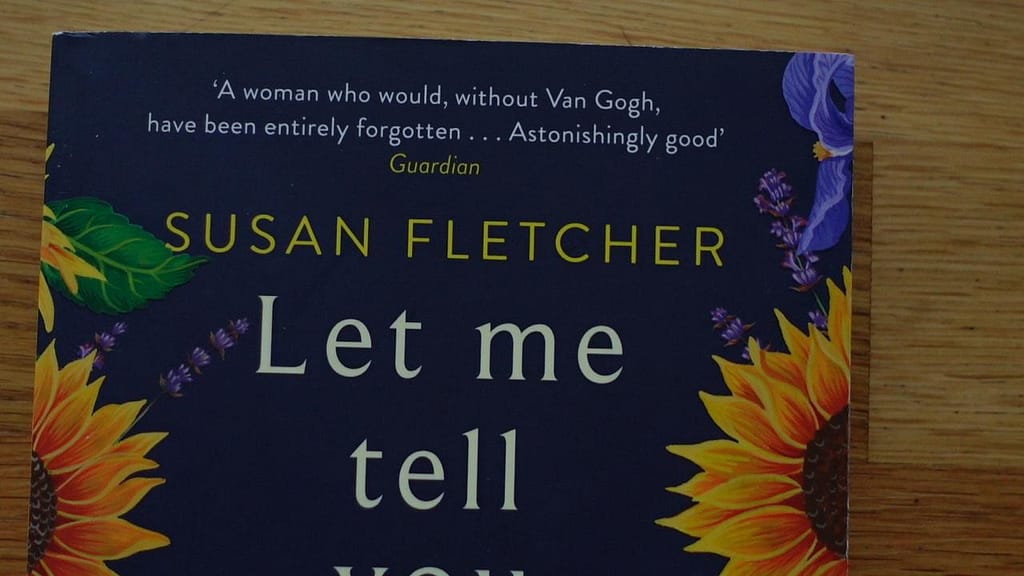

Let me tell you about a man I knew, by Susan Fletcher

Susan Fletcher’s discreet yet charming novel, Let me tell you about a man I knew, explores Vincent’s brief stay at the Saint-Rémy-de-Provence sanatorium in 1889. The story is told from the perspective of Jeanne Trabuc, the wife of the warden and executive director of the asylum, a real person that Van Gogh actually painted, as well as her husband. These historic facts are the starting point of a story that speaks of freedom and joy, of tones and undertones oinsouthern light, of purpose and calling.

Many paintings would suit this story, but his irises on yellow background have mesmerised me in Amsterdam :

“Prussian Blue. They say there’s no colour such as that in this world, but I can tell you I’ve seen it. Night skies and water. I used it in cypress trees. Those irises had it – the ones by the boundary wall that you found me painting. And this, see it ?” he lifts up a tube.

“Yellow”

“More than yellow. Cadmium yellow. It’s in grass and dry earth, in mornings. I did sunflowers in Arles. This colour”- he speaks more softly now, as if confiding – “this is the colour of life to me. This, and the blue; I favour them together because there are some colours that bring out the brightness in another. I’ve told Théo this. I’ll need more Prussian blue soon.”

― Susan Fletcher, Let me tell you about a man I knew

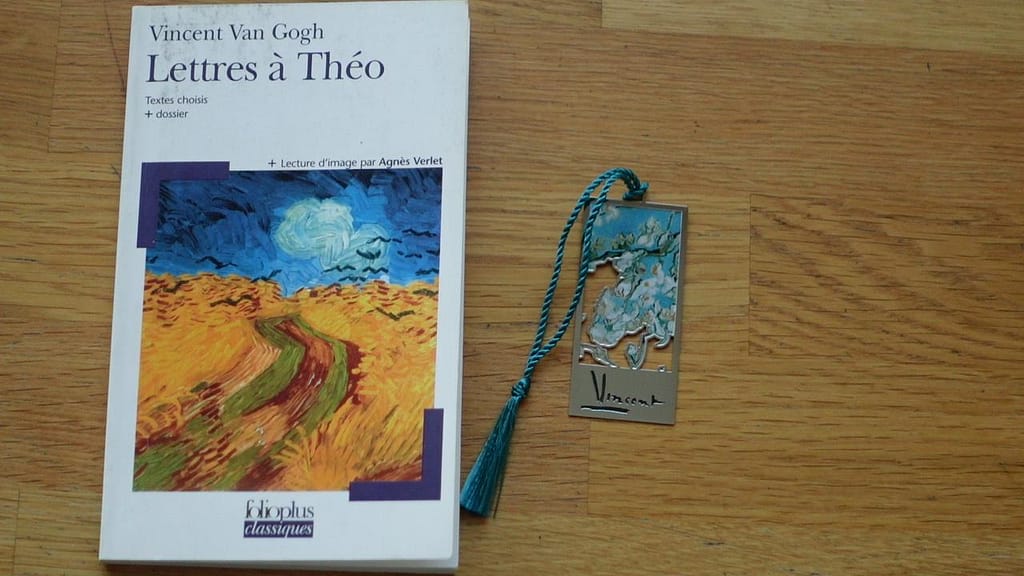

Letters to Théo, by Vincent Van Gogh

Historical fiction has the special power to bring people and events back to life in such a powerful and unforgettable way. But in Van Gogh’s case, we have the incredible privilege of reading his own words, in his correspondance with his brother Théo. Between the raw, almost painful honesty of this letters, and the multitude of his self-portraits, each and every one of us can have a private meeting with the artist.

It can be overwhelming to read of his deep sadness, of his never belonging in spite of always searching for a higher purpose, but what I found in his letters, is what we ultimately see in his paintings : a colour so intense and so luminous in his spirit, that it can break the dense fog of the mind.

“It is true that I am often in the greatest misery, but still there is within me a calm pure harmony and music. In the poorest huts, in the dirtiest corner, I see drawings and pictures. And with irresistible force my mind is drawn towards these things. More and more other things lose their interest, and the more I get rid of them, the quicker my eye grasps the picturesque things.”

― Vincent van Gogh, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh

Eight books and three destinies, my Dutch experience of the masters of painting has been so enriching. There are many more books on the subject out there, and I’m curious to know if you would recommend any of them. If ever in Amsterdam, the three places to be if you’re interested in these artists are of course the Rijksmuseum, the Rembrandt House and the Van Gogh Museum. I have enjoyed my visit of the three, but I urge you to choose weekdays or low tourist season if you wish to take your time.

And in the end, take Vincent’s advice :

“Admire as much as you can, most people don’t admire enough.”

― Vincent van Gogh

Until next time, enjoy your reading and your rituals !

If you would like to support The Ritual of Reading, please consider purchasing your books from the Bookshop.org dedicated site by clicking the link below. You get to support local bookstores and I make a small commission with every purchase. Thank you !