The first time someone sneezed at my office in Paris, everyone pretended it never happened.

I sat frozen, caught between my impulse to say à tes souhaits (bless you) and the realization that my colleagues had collectively decided to ignore this perfectly natural bodily function. Later, someone explained: it’s considered more elegant not to embarrass the person by acknowledging something indelicate in public. Which, if I’m honest, still feels absurd—sneezing is hardly a scandal—but it was my first lesson in a particularly French contradiction: the coexistence of egalitarian ideals with an unwavering commitment to refined behavior.

As an adopted French citizen, I’ve always felt that understanding the rules and etiquette of the country I chose to live in is something of a duty. I was born and raised in a country that worshiped French manners, that imported France’s customs about everyday life almost wholesale. So adapting wasn’t as straining as you might think. But there were surprises. Because the French are both the precursors of everything related to etiquette in the Western world and at the same time the ones who seem to challenge it most vigorously in the modern day.

After exploring American and British etiquette, crossing the Channel to France felt inevitable. If Emily Post gave us architecture and William Hanson reclaimed courtesy with wit, what would the French—who literally decapitated their monarchy—have to say about manners?

The Republican Protocol: Jacques Gandouin’s Guide to French Courtesy

The bestselling Guide du protocole et des usages by Jacques Gandouin is already on its seventh edition and remains the most widely referenced guide to French etiquette today. Though Gandouin passed away more than twenty years ago and the book’s most recent revision dates to 2002, it continues to hold its position as the definitive text—perhaps because certain fundamentals of French courtesy have remained remarkably stable, even as the world around them transforms.

Gandouin’s credentials are impeccable: he was the artisan of the new official protocol of the French Republic. This wasn’t merely theory—this was the man who codified how the French state would present itself to the world. His book reflects this dual nature: part manual for navigating everyday social situations, part blueprint for official ceremony. And unlike his Anglo-American counterparts, Gandouin wrote with the humor and bon sens that characterize French approaches to rules—a kind of winking acknowledgment that yes, these things matter, but we’re not taking ourselves too seriously about it.

Reading Gandouin after the British and American guidebooks, I recognized a certain similarity in structure. Greetings, introductions, correspondence, table manners—the expected chapters all appear. But the differences emerge quickly. Right from the opening sections, the French guides include something very specific: le baisemain, the art of kissing a woman’s hand. Even if this custom is becoming increasingly rare, the correct way to perform it is still considered worthy of instruction. There’s a formality here, a preservation of gesture that feels distinctly French.

Then there’s the linguistic dance of tu versus vous—that delicate calibration of intimacy and respect that exists not just in French but across all Romance language cultures. The rules are complex, shifting with context, relationship and even politics. To use tu prematurely is to presume; to cling too long to vous is to remain distant. Gandouin dedicates careful attention to this, understanding that language itself is a form of courtesy.

But the chapter that struck me most profoundly, the one that feels embedded in the very DNA of French society, concerns the rules of status and hierarchy. The American books mention “Best Society” but underline that it has nothing to do with wealth. William Hanson acknowledges the historic importance of class and nobility in British society, even today. But the French? They draw the spine of their contemporary etiquette from the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, dating back to the Revolution of 1789.

Quick Guide: The Tu vs. Vous Hierarchy

Use Vous: By default with anyone you don’t know, superiors, shopkeepers and elders.

Use Tu: With children, pets, close friends and family.

The Golden Rule: Always wait for the elder or the person in the higher professional position to say, “On peut se tutoyer?” (Can we use ‘tu’?) before switching.

Gandouin explains that the equality between citizens—one of the fundamental rights upon which French society is built—does not exclude a hierarchy of values. The Declaration honors each citizen not because of wealth or birth, but according to ability, with no other distinction than that of virtues and talents. This is the principle that France exported with great success, the principle that shapes so many societies today. Merit, not money. Virtue, not lineage. An egalitarian hierarchy—if such a paradox can exist.

Modern Savoir-Vivre: The Larousse Approach to Social Manners

The second book I explored was Le Petit Larousse du Savoir-Vivre aujourd’hui by Sabine Denuelle and it fascinated me precisely because of how it structures its approach to courtesy.

The first section is called Avec soi-même—”With Yourself.” Before you learn how to greet others, before you master table settings or correspondence, you must first attend to your own presentation: clothing, jewelry, personal hygiene, appearance. But also less tangible things—your tone of voice, your laughter in public, your use of your mobile phone, the way you look at others, even how you master your mood and temper when among people.

Only after establishing this foundation of self-presentation does the book move to interactions with others: greetings, cohabitation, reactions to incivility, olfactory and auditory nuisances, punctuality. It’s a psychological structure that Eleanor Roosevelt would have appreciated—the insistence that courtesy begins with self-cultivation—but with a distinctly French emphasis on aesthetic self-presentation.

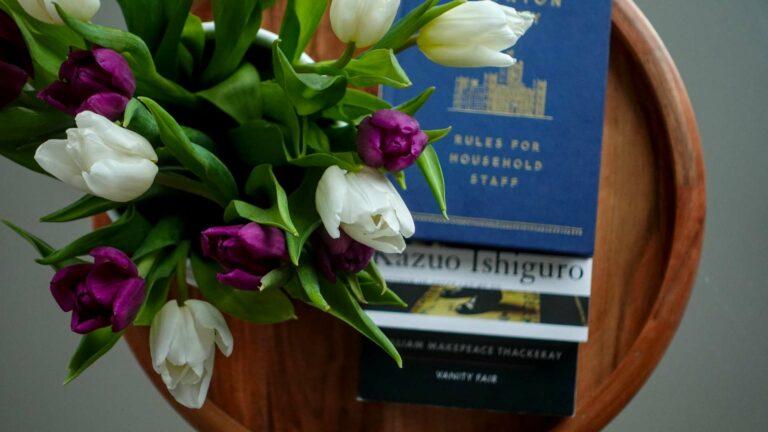

Then comes communication itself, both verbal and written. And finally—because of course it must—table manners. For a country that lives for its food, this section is predictably thorough. I was particularly surprised to learn that arriving at a dinner invitation with flowers is not, in fact, the correct thing to do. Why? Because it would compel your host to sort out the vase situation when their presence might be required elsewhere. The proper approach: send flowers in advance by delivery service, or after the party as a thank you.

It’s the kind of detail that perfectly captures French etiquette—thoughtful, aesthetic, but above all practical in its consideration of the host’s experience.

Savoir-Vivre Pro-Tip: The Dinner Party

The Flower Rule: Never bring a bouquet to the door. Send them via a florist on the morning of the dinner or a “thank you” note with flowers the following day.

The Bread Rule: Never bite directly into a roll. Break off a small, bite-sized piece with your fingers.

The Wine Rule: Never fill your own glass. Wait for the host, and never fill a glass more than halfway to allow the aromas to breathe.

The Tables of Power: How French Elegance Survived the Revolution

This whole exploration of table manners reminded me of an exhibition organized at the Louvre-Lens a few years back: Les tables du pouvoir, Une histoire des repas de prestige (The Tables of Power: A History of Prestigious Meals). The exhibition spanned 5,000 years of culinary history, from Mesopotamia to the Élysée Palace, with nearly 400 works including archaeological objects, paintings, tableware and prestigious objets d’art.

The exhibition catalogue is a wonderful document that traces customs and protocols from Antiquity to modern-day Republican etiquette. It’s both a reminder of the evolution of rules throughout the centuries and—to my great delight—a showcase of the exquisite tableware that accompanied these manners. Because if there’s one thing the French understand, it’s that beauty and function are not opposites but partners.

For centuries, meals have been opportunities to showcase power, hierarchy and the art of protocol, from ancient liturgical banquets to Louis XIV’s grand couvert. The customs have constantly evolved—from eating while reclining to sitting at tables, from service à la française to service à la russe—but the underlying principle remains: the meal is theater and the table is a stage.

What struck me most about this exhibition and about French etiquette more broadly, is a fascinating paradox: for a country that decapitated its kings and denied in the most violent of ways anything related to class or privilege, France remained surprisingly attached to the idea of manners and even protocol.

Other famous revolutions around the world erased the traces of the upper class and with them, all notion of elegance and respect. But the French seem to have been determined to prove that elegance and respect are not the preserve of the rich, but the choice of every person who respects themselves and others. The Revolution didn’t abolish courtesy—it democratized it.

Practicing Politesse: Observing Modern French Manners in 2026

Some might argue that 2026 France is not as keen on preserving these values as it once was. And there’s truth to that—walk down any Paris street and you’ll witness plenty of violations of the old codes. The world has changed. Formality has loosened. The baisemain has all but disappeared.

And still.

In the crazy whirlwind that is Paris—a city that breathes both the Chanel No. 5 of the Rive Gauche elite and the hip-hop dance of the suburb kids—you see people giving up their seats in the metro for strangers. You can have a wonderfully pleasant conversation with the greengrocer at the market. You’re served with the utmost respect by the waiter at any local brasserie, provided you treat them with the same respect upon entering their establishment.

That last part is crucial. French courtesy is often reciprocal in ways that can surprise newcomers. The shopkeeper who seems cold until you greet them properly. The waiter who warms immediately once you’ve shown basic politesse. It’s not servility—it’s mutual recognition of dignity.

Like any country around the world, France functions by following certain rules. Luckily for us foreigners who want to understand its mechanism, there are books to explain, museums to visit and daily life to observe. Modern French savoir-vivre is not about memorizing which fork to use (though that helps). It’s about understanding that courtesy—even in a republic that proclaimed all men equal—is how we acknowledge each other’s humanity.

The French didn’t abandon etiquette after the Revolution. They transformed it from a mark of privilege into a practice of citizenship. From a way to display superiority into a way to create community. The forms may seem antiquated, the rules occasionally absurd, but underneath runs a consistent thread: we share this space, this society, this table—and the way we treat each other matters.

Is French Etiquette “Snobbish”?

While often perceived as elitist, French politesse is rooted in the Republic’s egalitarian ideals.

The Goal: To acknowledge the “Dignity of the Citizen.”

The Result: This is why a French waiter expects a “Bonjour” before an order; they are your fellow citizen, not your servant.

That’s what savoir-vivre means, literally: knowing how to live. Not just how to behave, but how to live well, together, in a world where equality and elegance can somehow coexist.

Even if it means occasionally pretending you didn’t hear someone sneeze.

The Reading List: Essential French Etiquette Books

For the Republican Perspective: Guide du protocole et des usages by Jacques Gandouin – 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For Modern French Living: Le Petit Larousse du Savoir-Vivre aujourd’hui by Sabine Denuelle – 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Visual Feast: Les tables du pouvoir: Une histoire des repas de prestige (Exhibition Catalogue) – 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A short note on how and why I share book links

What’s your relationship with French etiquette?

Have you encountered the tu/vous dilemma, mastered the art of greeting shopkeepers, or puzzled over the Bonjour / Bonne journée choice ?

I’d love to hear your observations in the comments below.

Note: This is Part III in my series “The Art of Living Among Others,” exploring etiquette and good manners guides through several cultures and languages.

Read Part I: In Defense of Good Manners and Part II: On English and American Etiquette to follow the journey from philosophical foundations through Anglo-American traditions to French Republican courtesy.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.

Enter The Ritual of Reading

Each Sunday, receive a letter to steady your attention—literary inspiration, seasonal rituals and reflections from a life shaped by books.

On the first of each month, a gift: The Literary View, a custom wallpaper created to accompany your days.