There’s a particular kind of magic that happens when you read French poetry while sitting in a Paris café—the rain drumming against the window, a cup of something warm between your hands, the city murmuring around you. It’s as though the words on the page and the streets outside begin to speak to one another, and suddenly you understand why Paris has always been a poet’s city.

But here’s the secret that poetry itself reveals: you don’t have to be in Paris to experience this magic. The right poem, the right poet, can transport you there completely. It can remake the ordinary into the extraordinary, turn a rainy afternoon into an adventure, a moment of melancholy into something luminous and true.

If you’ve ever wondered where to begin with French poetry—if the very thought of it seems either too intimidating or too abstract—let me offer you a different approach. Rather than studying poetry, what if you simply let yourself be carried away by it? What if you stopped trying to understand every line and instead surrendered to the music, the images, the feeling?

French poetry isn’t meant to be conquered. It’s meant to be inhabited.

Charles Baudelaire: The Poet Who Found Beauty in Darkness

When you think of Paris—the real Paris, not the postcard version—you’re likely thinking through Baudelaire’s eyes whether you know it or not. He was the first to look at the city’s underbelly and see not degradation but depth, not squalor but a strange, intoxicating beauty.

Baudelaire understood something crucial: beauty isn’t always pleasant. It can be dark, troubling, even repugnant. His flowers bloom in cemeteries. His lovers are mysterious, unreachable, sometimes cruel. In Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), he transformed the gritty, gaslit Paris of the 19th century into something mythic—a city where every street corner holds a secret, every shadow hides a story.

Start with him if you want poetry that doesn’t look away. Read him if you’re drawn to melancholy, if you understand that beauty and sadness are often intertwined, if you’ve ever found something achingly lovely in a moment of despair. Baudelaire teaches you to pay attention to what the world considers unworthy, and in doing so, he teaches you to truly see.

His language is dense and sensual, built on carefully chosen images that stick with you long after you’ve finished reading. This is poetry that demands to be read aloud, that rewards you with its musicality even—or especially—when you don’t understand every word.

A Fragment to Begin:

“I am the wound and the blade, the torturer and the flayed.”

In conversation with :

Debussy’s Clair de Lune — Baudelaire writes in the mid-19th century about the beauty hidden in corruption and decay, while Debussy composes at the century’s turn, dissolving traditional form into impressionistic mist. You might think they inhabit different artistic worlds—Baudelaire the moralist cataloguing urban decay, Debussy the innovator questioning whether music should follow rules at all. But listen closely: both are painting the same territory. Debussy’s moonlight is Baudelaire’s shadow, rendered in sound. Both artists understood that beauty doesn’t reside in what’s pleasant or obvious—it lives in what’s subtle, layered, sometimes troubling. The piano’s delicate dissonances mirror the emotional complexity of Baudelaire’s paradoxes. Here is proof that sensibility transcends technique: whether through words or through music, a profound soul finds the same hidden beauty, generation after generation.

Arthur Rimbaud: The Rebel Who Rewrote the Rules

If Baudelaire is the poet who sees beauty in darkness, Rimbaud is the poet who refuses to sit still long enough to be pinned down at all. A prodigy who wrote most of his significant work before he was twenty, Rimbaud approached poetry like an alchemist approaches lead—convinced that through sheer will and experimentation, he could transform it into something completely new.

His most famous work, A Season in Hell, reads like a fever dream, a spiritual crisis, a rebellion against everything conventional. Rimbaud doesn’t just break the rules of poetry; he sets them on fire. His sentences spiral and shift, his imagery leaps impossibly from one vision to another, and yet somehow it all holds together in a kind of lunatic coherence that feels absolutely true.

What makes Rimbaud essential for understanding Paris is this: he represents the city at its most anarchic and alive, the Paris of student revolutions and artistic rebellion, where a young man could arrive with nothing and remake himself completely through sheer audacity and talent. He’s the poet to read when you want to feel that electricity, that sense that anything is possible, that the old ways are crumbling and something new is being born.

Fair warning: Rimbaud will disorient you. But that disorientation is part of his gift. He’s teaching you to see differently, to think in fragments and leaps, to trust your intuition over logic. Read him when you’re ready to be shaken.

A Fragment to Begin:

“Once, if my memory serves me well, my life was a banquet where every heart revealed itself, where every wine flowed.”

In conversation with :

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring — Rimbaud shatters conventional form at age nineteen; Stravinsky does the same with music thirty years later, and audiences riot both times. The parallel is uncanny. Both were young men who understood that art needed to break itself apart and reassemble differently to tell the truth about human experience. Stravinsky’s jarring rhythms and primitive energy don’t feel refined or apologetic—they’re deliberately chaotic, exactly as Rimbaud’s hallucinatory language refuses to make sense in traditional ways. Yet beneath the disruption in both lies genuine power: the revolutionary fervor, the sense that the old world is collapsing and something raw and necessary is being born. When you pair them, you realize that the chaos isn’t nihilistic—it’s passionate. Both artists are trying to shake you awake, to make you feel something you’ve never felt before. Sensible souls across centuries recognize that sometimes beauty requires breaking everything first.

Paul Verlaine: The Poet of Longing and Whisper

While Rimbaud burns bright and burns fast, Verlaine smolders. His poetry is quieter, more intimate, built less on grand gestures and more on delicate precision—a perfectly chosen word, a subtle shift in rhythm, a whisper that somehow reaches farther than a shout.

Verlaine understood music in a way that’s almost impossible to translate into English. His famous dictum—”Music above all else”—wasn’t just a preference, it was a philosophy. He believed that poetry should sound beautiful first, communicate meaning second. His verses flow like melody; reading them aloud is less like reading and more like singing.

His Paris is a different Paris from Baudelaire’s. Where Baudelaire finds beauty in the corrupt and shadowy, Verlaine finds it in absence, in longing, in the bittersweet ache of loving something you can’t quite hold onto. His poems about autumn—that melancholy season—are some of the most perfect expressions of gentle sorrow ever written. There’s no drama in Verlaine, no rebellion. Just a profound tenderness toward human weakness, toward disappointment, toward the quiet ways we fail each other.

Read Verlaine when you want to feel seen in your own sadness, when you need poetry that acknowledges that sometimes life is simply heartbreaking and that’s okay. Read him for the pure pleasure of the sound, even if the meaning remains slightly beyond your grasp. Sometimes the music is the meaning.

A Fragment to Begin:

“The long sobs of autumn’s violins

Wound my heart with a monotonous languor.”

In conversation with :

Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies — Verlaine said “Music above all else,” and here’s the composer who truly understood what he meant. Satie composed these pieces decades after Verlaine wrote, yet they’re the perfect realization of Verlaine’s aesthetic: sparse, unhurried, built on the fewest possible notes to create maximum emotional resonance. There’s no flourish, no unnecessary ornament. Just the essential sadness of existence expressed with absolute clarity. When Verlaine speaks of autumn’s violins wounding the heart, Satie answers with piano keys that sound almost like those violins—mournful, repetitive, hypnotic. Both artists believed that restraint is more powerful than excess, that beauty emerges from knowing what to leave out. Listen to the Gymnopédies while reading Verlaine, and you’re hearing two different artists across time speaking the same language: the language of tender, patient sorrow. This is what sensible souls understand: sometimes the most profound truths can only be expressed in whispers.

Guillaume Apollinaire: The Modern Poet Who Loved the City

By the time Apollinaire was writing, Paris was transforming. The Belle Époque gave way to the new century with all its speed and fragmentation and possibility. Apollinaire wasn’t content to write about the old Paris; he wanted to capture the new one—the Paris of automobiles and airplanes and electric lights, the Paris where the future was happening in real time.

What’s remarkable about Apollinaire is his ability to blend the lyrical with the modern, the romantic with the technological. He wrote about love with genuine tenderness, but he also wrote poems that look like pictures on the page, that play with typography and spacing as much as with words. He was endlessly curious, endlessly inventive, restlessly moving between forms and styles.

His Alcools collection captures a Paris that’s simultaneously timeless and utterly contemporary—a city that’s always in the process of becoming something new. You’ll find in his work the wandering poet, the dreamer, the observer of street scenes and casual encounters, but also something more experimental and dare-I-say playful about the possibilities of what a poem could be.

Read Apollinaire when you want poetry that embraces contradiction, that moves seamlessly between the tender and the irreverent, that treats the city not as a monument but as a living, breathing, constantly changing presence. He’s the poet who understood that you don’t have to choose between tradition and innovation—you can honor both at once.

A Fragment to Begin:

“Under the Mirabeau Bridge flows the Seine

And our loves

Must I recall

How joy always followed pain?”

In conversation with :

Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess — Apollinaire gazes at the Seine flowing beneath the bridge and watches time carry away everything he loves; Ravel, a few years later, composes music about memory and loss without naming them directly. Both artists are meditating on the same mystery: how does one live with the knowledge that all things pass? Apollinaire’s poem moves with the river’s current—elegant, flowing, yet marked by an undertone of inevitability. Ravel’s piano mirrors this perfectly: the melody glides forward with aristocratic grace, yet there’s a weariness in it, a recognition that even beauty is temporary. What’s remarkable is that neither artist is bitter or despairing. Instead, both seem to suggest that the transience of things is precisely what gives them their poignancy, their value. When you sit with both together, you understand that sensible souls recognize this paradox across the ages: the impermanence of love doesn’t diminish it. It deepens it. Makes it matter more.

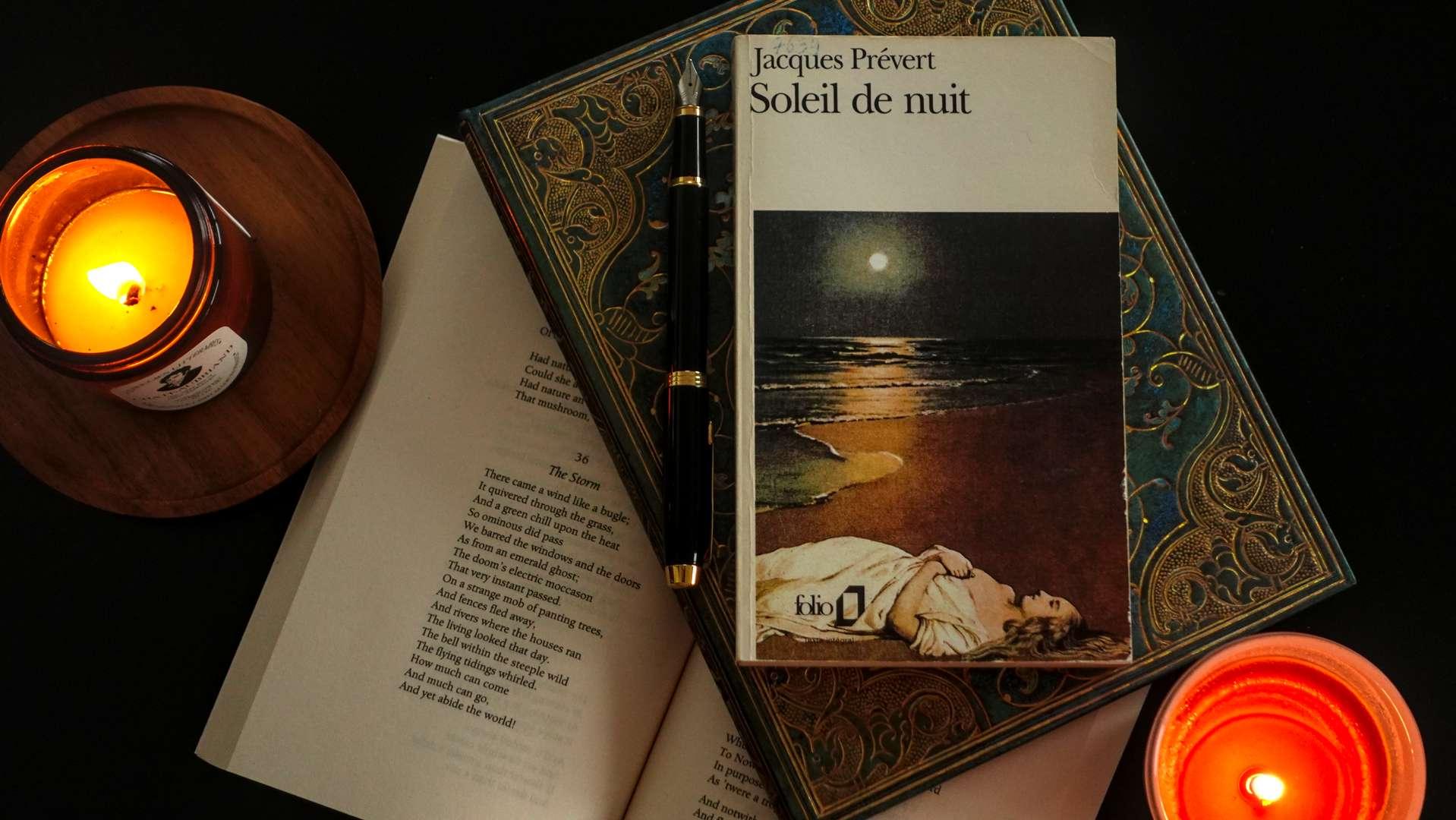

Jacques Prévert: The Poet for Everyone

If the others can feel a bit rarified, Prévert is the poet who met French poetry and said, “What if we just talked to each other like actual people?” His work has a deceptive simplicity—he uses everyday language, familiar situations, casual rhythms—and yet beneath that accessibility lies something profound and often heartbreaking.

Prévert loved Paris with an uncomplicated devotion that’s almost touching. He loved its parks and its prostitutes, its children and its old women, its cafés and its street musicians. His Paris is democratic in the truest sense—everyone and everything has equal poetic value. A love affair matters as much as a bird landing on a wire. A child’s game matters as much as a philosophical meditation.

What I adore about Prévert is his refusal to be precious about poetry. He writes as though he’s telling you something over a glass of wine, with warmth and humor and unexpected gentleness. He’s funny without being frivolous, accessible without being simple-minded. His most famous work, Paroles (Words/Sayings), reads like the collected wisdom of someone who’s paid very close attention to life and isn’t afraid to share what he’s noticed.

Start with Prévert if poetry still feels foreign to you, if you want words that feel like friendship rather than instruction. Read him to remember why we write at all—not to impress, but to connect, to say “I was here, I saw this, and it mattered.”

A Fragment to Begin:

“Three matches one by one struck in the night

The first to see your face in its entirety

The second to see your eyes

The last to see your mouth

And the darkness all around to remind me of all these

As I hold you in my arms.”

In conversation with :

Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2 — Here lies a beautiful collision: Prévert, the 20th-century street poet who refused elegance, paired with Chopin, the 19th-century Romantic who elevated melancholy into high art. They seem like opposites—Prévert speaks in the language of Paris cafés and cigarette smoke, while Chopin composes for concert halls and candlelit drawing rooms. And yet. When you listen to that nocturne’s delicate, searching melody while reading Prévert’s three matches lighting up the darkness, you realize something profound: the longing is the same. The way a sensible soul touches the face of the beloved in the dark—that’s universal. That’s timeless. Whether you’re a 19th-century Polish composer or a mid-20th-century French poet, if you’ve ever loved someone, you understand this moment perfectly. The music and the words speak across their centuries and find each other, because true tenderness recognizes itself wherever it appears.

Creating Your Own Poetry Ritual

The beauty of French poetry is that it asks very little of you except your presence and your willingness to listen. You don’t need to understand every reference or decode every image. Poetry works on you whether you fully comprehend it or not—it enters through your ears, your senses, your intuition.

Consider gathering a collection and creating a ritual around it. Read one poem slowly, perhaps twice, perhaps aloud. Don’t rush to understand it. Instead, notice what images stay with you, which lines echo in your mind as you walk through your day. That’s the poetry working. Play the accompanying classical piece softly in the background—let the music and the words speak to each other.

If you’re in Paris, find a café that feels like yours and spend an afternoon with these poets. If you’re elsewhere, create that Parisian corner wherever you are—a comfortable seat, a warm drink, the sense that time has slowed down just for this moment. Let the city in the poems become the city around you.

Most of all, give yourself permission to feel what these poets felt. Their longing, their rebellion, their tenderness, their wonder. That’s not escaping into nostalgia or fantasy. That’s the most authentic experience of poetry there is—the moment when the distance between you and the poet collapses, and for a brief time, you’re both looking out at the world with the same eyes.

The invitation, as always, is simply this: read. Let yourself be transported. Let Paris—the Paris of dreams, of beauty, of contradiction—become real again, one poem at a time. Let the music carry you.

Until next time, enjoy your reading—and the poetry you find in ordinary moments.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.