The classics can be either fascinating or daunting, their style moving farther and farther away from our fast-paced minds, the universe they describe becoming more and more abstract.

Reading the pillars of a nation’s literature has become synonymous with school chores and obligation. We were taught that whether we understand them or not, they are to be venerated, and for the most part the lessons and meanings of their work have been pre-extracted for us, our attention already directed toward what critics and historians believed to be important.

But here’s what they don’t tell you in school: the critics can be wrong. Or at least, they can be wrong for you.

What if we were to reclaim our classics? What if your understanding of them—raw, personal, unfiltered by academic consensus—matters more than the approved interpretation? What if these books, written in centuries past, still have something urgent and intimate to say to you, right now, in your own voice?

In my endeavor to bring French classics to international readers, I find myself returning to titles that once felt like homework, rediscovering them as something else entirely: as companions, as revelations, as windows into ways of seeing that feel both utterly foreign and deeply familiar.

The French Literary Soul: Where Life Becomes Art

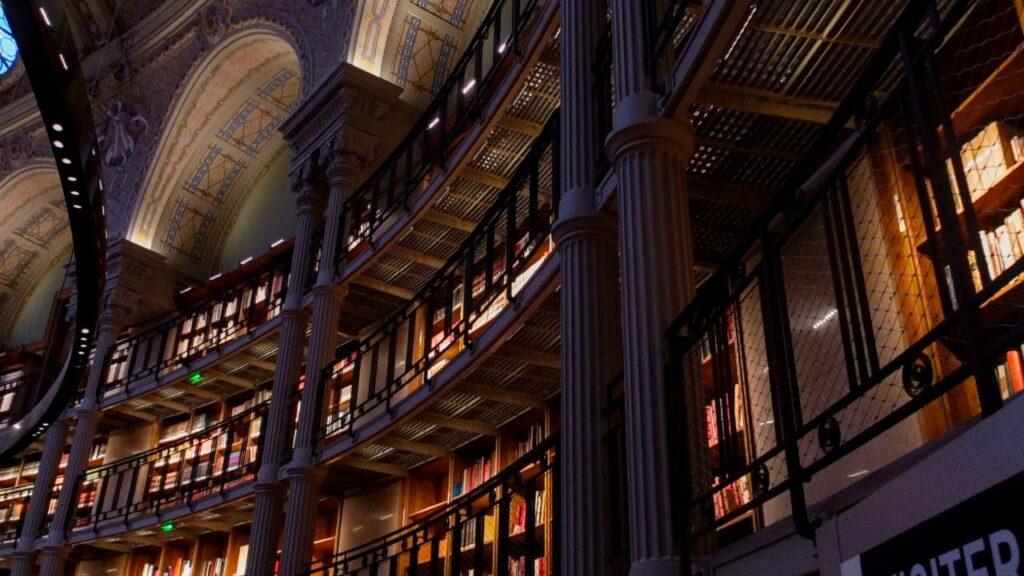

To understand French classics, you must first understand something about French culture itself: the profound belief that literature is not separate from life, but essential to it. In France, writers aren’t just entertainers or intellectuals—they’re cultural architects, philosophers of everyday existence, guardians of language and thought.

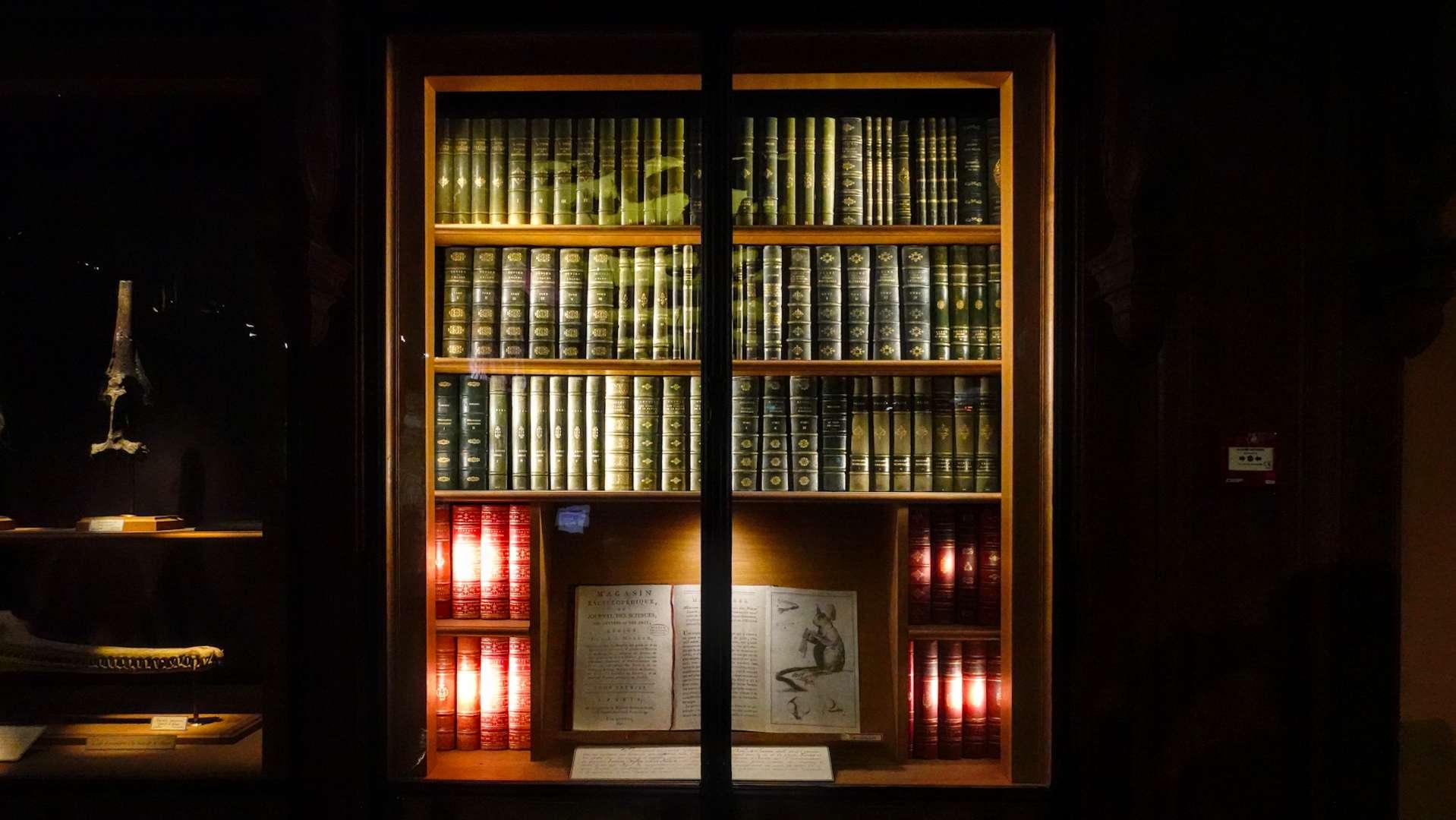

The salon culture of the 17th and 18th centuries created a tradition where literature was meant to be discussed, debated, dissected over wine and candlelight. Books were social currency, ideas were exchanged like gifts, and the art of conversation was considered as important as the art of writing. This DNA still runs through French literary culture: the assumption that books are meant to be lived with, argued about, returned to again and again.

The habit might have dialed down these past few decades, but remember the rentrée littéraire with its yearly celebration of new books being published, remember the literary events that most bookshops organise monthly, meetings with authors and debates on great ideas coming from books. France still has a weekly TV show dedicated to literature, a fascinating mix of reviews and interviews with the authors present on set and exchanging about each other’s books. And last but not least, ever since 1981 France has adopted a law which establishes a fixed price for books sold in France and limits price discounts on them, thus eliminating competition between small book sellers and large chain bookstores.

Why Return to French Classics This Autumn

There’s something about the turning season that makes these books feel newly relevant. As the days shorten and the world pulls us back indoors, as summer’s extroversion gives way to autumn’s introspection, the French classics offer a particular kind of companionship. They offer something our fast-paced, algorithm-driven world increasingly lacks: depth, nuance, the willingness to sit with complexity rather than resolve it. They remind us that some questions don’t have answers, that ambiguity can be more truthful than certainty, that life’s richness often lies in the spaces between clear-cut positions.

And they offer us beauty—not as decoration, but as sustenance. Flaubert’s carefully constructed sentences, Maupassant’s devastating emotional precision, Zola’s overwhelming sensory abundance—these aren’t just pleasant; they’re nourishing in a way our souls quietly crave.

So if you’re new to French literature, or if you simply wish to give it another chance—this time on your own terms, in your own season—here are my five essentials for an authentic introduction to French classics.

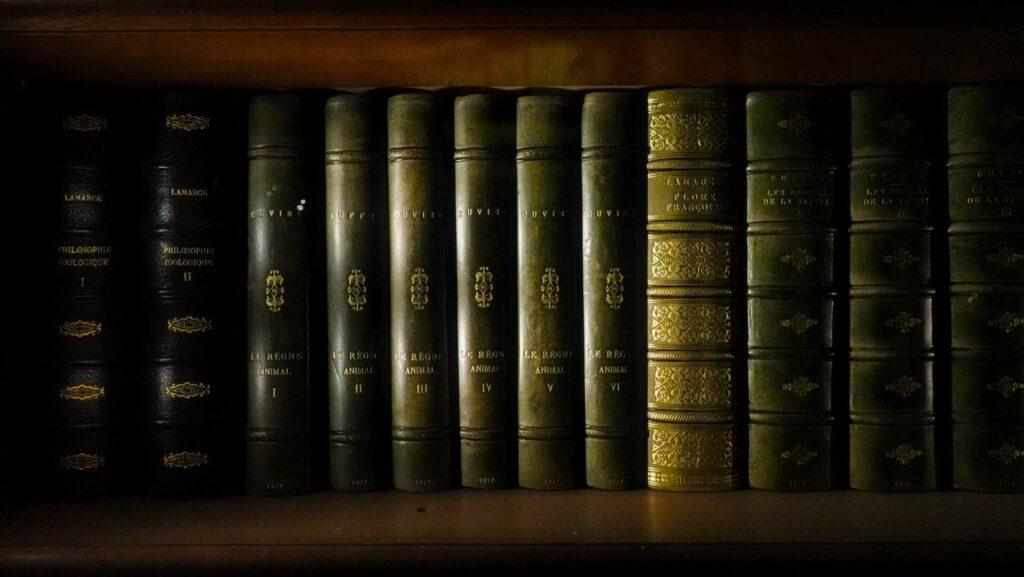

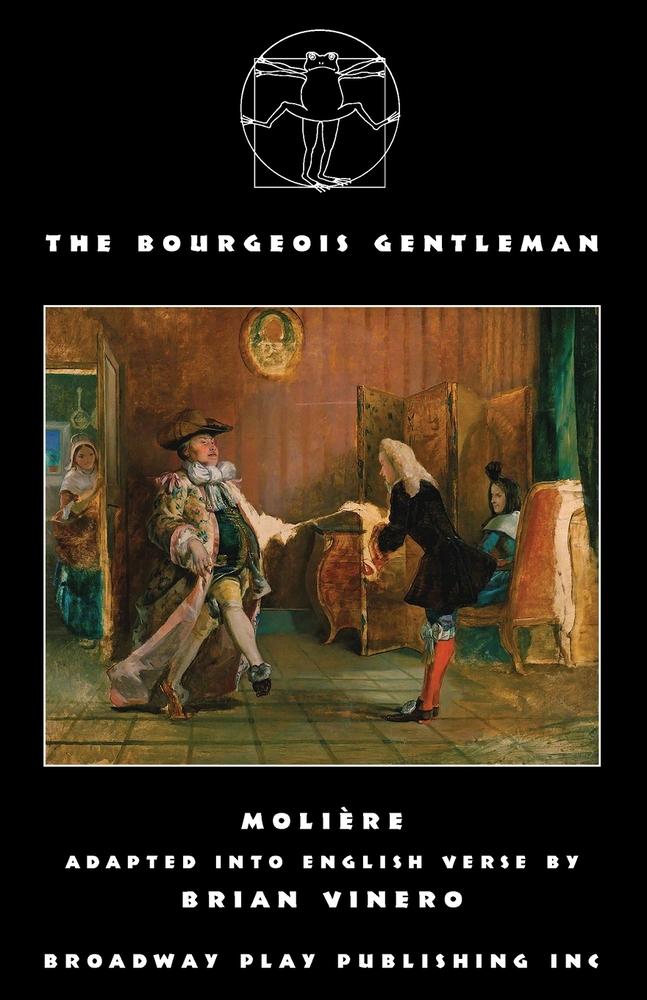

Molière – Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme

(The Bourgeois Gentleman)

When Monsieur Jourdain discovers, to his absolute delight, that he’s been speaking prose all his life without knowing it, we witness one of literature’s most perfect comic moments. This 17th-century play follows a wealthy middle-class man desperately trying to transform himself into an aristocrat, hiring tutors in music, dance, philosophy, and fencing—and becoming, in the process, utterly ridiculous.

My love of Molière knows no boundaries. I love his wit and sarcasm, his phenomenal sense of comedy that hasn’t lost a bit of its freshness. It’s not often you can read a 17th-century play and feel like it was written yesterday, the characters so current and relatable, the human vices so utterly the same four centuries later.

His plays have a lively, jolly feel to them that reads like entertainment more than great literature, and perhaps that was his greatest talent: you can experience his writing on several levels of understanding, from the comic first degree to the profound analysis of society. Choose one or reflect on all of them—either way, Molière will conquer you through his exceptional sense of distilling essence through humor. His genius lies in making you laugh at pretension while recognizing, with a slight uncomfortable twist, your own small vanities reflected in his characters.

Guy de Maupassant – Une Vie

(A Life)

Jeanne, a young Norman woman full of romantic dreams, leaves the convent for married life—and discovers, gradually and painfully, that reality rarely matches our hopes. This novel traces an entire life, from youthful optimism through disillusionment, betrayal, and loss, until its devastating and tender final line.

I’ve recently mentioned this as being the first French novel I ever read, and the great impact it had not only on my reading life but on my life in general. Maupassant is famous for his novellas; critics agree that the shorter form suits his excellent sense of character description and provincial life settings. However, I found his novel A Life utterly immersive. The rhythm and intrigue felt perfectly suited for the atmospheric read. It holds a special place in my heart and stands as one of the great examples in my reading life that I should trust my instinct before I believe the critics.

There’s something almost cruel in Maupassant’s clear-eyed observation of how life can slowly erode our dreams, yet something deeply compassionate too—as if he’s saying, “I see you, I know it hurts, and I’m bearing witness.” It’s the kind of book that changes how you see your own life, that makes you hold your joys a little closer and forgive your disappointments a little more gently.

Gustave Flaubert – Madame Bovary

Emma Bovary, a doctor’s wife in provincial France, suffocates under the weight of ordinary life. Raised on romantic novels, she expects passion, elegance, transcendence—and instead finds herself trapped in tedious domesticity. Her attempts to escape into love affairs and luxury lead to one of literature’s most haunting portraits of desire and despair.

Flaubert must be my most beloved French classic. He was called a perfectionist because of his particular writing style: he never wrote more than two pages a day, and kept only fragments of them, since the greatest test his writing had to pass was the music and rhythm of the phrases. Once the two pages were written, he started reading them aloud in search of balance, for a certain musicality that was certainly not found in alliterations or rhymes but in the harmonious sound of the phrase.

He was a true lover of language. I think that’s what makes me so passionate about his works—words held meaning not only by themselves, but in the whole composition of his phrases. These are the details that a linguist loves while reading great literature, but Flaubert was also celebrated for the unique stance of the narrator in his novels. Unlike his predecessors (we’ll speak of Balzac in a moment), Flaubert placed himself at the level of his characters, describing situations from their vantage point, making them so much more relatable to the reader.

If you haven’t sensed it yet, Flaubert is one of my favorite writers of all time, and if you were to pick just one from my list, he would definitely be the one. To read Flaubert is to understand that style isn’t decoration—it’s substance, it’s the very soul of the story made visible through language.

Honoré de Balzac – La Maison du chat-qui-pelote

(At the Sign of the Cat and Racket)

In a small, prosperous fabric shop on the Rue Saint-Denis, a young painter falls in love with Augustine, the merchant’s daughter. Their marriage seems like a romantic triumph—until the unbridgeable gap between artistic sensibility and bourgeois values tears them apart. It’s a compact tragedy of mismatched souls and the cruelty of social expectation.

If Flaubert’s narration got down to the level of the story, Balzac feels like Zeus telling a story from Mount Olympus. His narration analyzes the situation, the behavior of his characters, their inner dilemmas and dramas, as if he knew better than anyone what was really going through their minds. This translates into a heaviness of the writing that demands more context and a certain state of mind, but is it worth it? Absolutely. I believe his characters are worth getting to know—this is the excellence of Balzac’s writing. And since I’m in a Parisian mood this autumn, At the Sign of the Cat and Racket has the perfect Parisian atmosphere that he so masterfully described.

Balzac’s Paris is a city of social architecture as complex as its physical architecture—every street has its character, every profession its codes, every class its costume and customs. He understood that we’re all products of our time and place, even as we fancy ourselves free agents of our own destinies. Reading him is like getting an X-ray vision of society, seeing the invisible structures that shape every interaction, every marriage, every rise and fall.

This is a compact novella, perfect for those evenings when you want something substantial but not overwhelming, when you’re curious about how Paris became Paris, when you want to understand the social forces that still, in different forms, shape our lives today.

Émile Zola – Le Ventre de Paris

(The Belly of Paris)

Florent, a political exile who has escaped from a penal colony in French Guiana, returns to Paris half-starved and finds refuge in the magnificent new central market, Les Halles—Victor Baltard’s revolutionary iron-and-glass pavilions that housed the city’s food supply. Surrounded by mountains of food—glistening fish still smelling of the sea, pyramids of vegetables in every color imaginable, hanging game, wheels of cheese, gleaming cuts of meat—he becomes caught between the world of the prosperous, well-fed merchants (the “fat”) and his own revolutionary ideals (the “thin”). The market itself becomes a character: sensual, overwhelming, alive with abundance and appetite.

Finally, Zola is one of my most recent additions to the favorites pile, since I have long felt his socially heavy prose as being far from my personal taste. His reputation as a naturalist writer, documenting social problems with almost scientific detachment, made him feel like medicine rather than pleasure. However, this is proof that you should revisit your classics from time to time, especially when your own tastes and life experiences have evolved.

I’ve become more and more passionate about the way he captures the essence of the great changes of the 19th century—the modernization of Paris under Haussmann, the rise of department stores and market halls, the tension between tradition and progress, the way capitalism was transforming not just the economy but the very texture of daily life. His Parisian-based novels are a rare opportunity to experience time travel in a very real and immersive way.

The Belly of Paris is special to me not only because of the specific place in Paris that it brings back to life (sadly, the historic Halles de Paris are no longer there, replaced in the 1970s by a modern shopping complex and metro hub) but also because of a French cultural staple: le marché—the market. There are few more immersive experiences into true, authentic French living than going to a farmer’s market on a Sunday morning, and being able to read the inside stories of the greatest historical market of Paris is an experience every reader should have.

This is Zola at his most enjoyable—before his later, darker works. Here he’s still in love with Paris, still capable of wonder at its transformation, still finding poetry in butchers and fishmongers. Read it when you want to be transported, when you’re missing Paris, or when you want to see your own local market with fresh eyes, as a place of abundance and drama and very human stories.

Creating Your Own French Reading Ritual

The beauty of returning to these works now, as an adult reader free from the constraints of curriculum, is that you get to decide what matters. You might read Flaubert for the sentences, Molière for the laughs, Maupassant for the emotional precision, Balzac for the social world he builds, and Zola for the sheer sensory immersion. But more than that, you can create rituals around your reading that make these classics feel like lived experiences rather than completed assignments.

Consider adopting some French approaches to reading: find your café and become a regular, letting reading become woven into the fabric of your days rather than something separate from real life. Read with your senses—visit the market before reading Zola, notice the weather while reading Flaubert, let the physical world enhance the literary one. Keep a commonplace book in the French tradition, copying out favorite passages by hand, arguing with the text, making reading a conversation rather than consumption.

Create your own rentrée littéraire—your literary autumn—choosing one or two classics to read deeply rather than rushing through a list. Pair books with French films and music, read passages aloud to catch the rhythm Flaubert worked so hard to perfect, or revive the salon tradition by discussing these books with friends over wine and cheese.

Most importantly, give yourself permission to skip and return—the classics have waited this long, they can wait until you’re ready. Make these books yours in whatever way works for you: one chapter a month or listening to the audiobook version, writing down passages or simply giving in to dreaming. Let them become companions rather than monuments, conversations rather than commandments.

The Invitation

These five books are my invitation to you—not to venerate French literature from a distance, but to claim it as your own. To read with pleasure and curiosity, to argue with the critics, to find what speaks to you rather than what you’re supposed to admire.

The critics can be wrong. The textbooks can miss the point. Your experience of these books—raw, personal, shaped by who you are and when you’re reading them—is as valid as any approved interpretation. More valid, perhaps, because it’s yours.

So brew yourself a cup of tea (or pour a glass of wine), find a comfortable corner (or a good café), and let these French masters surprise you. They’ve been waiting patiently for centuries, but they were never meant to be untouchable monuments. They were meant to be read, argued with, loved, underlined, returned to, lived with.

They were meant, above all, to be enjoyed.

What are your favorite French classics? Have you tried any of these titles? I’d love to hear which ones speak to you—or if there’s a classic you’ve been meaning to revisit now that the days are growing shorter and the reading light a little warmer.

Until next time, enjoy your reading and the French rituals you make yours!

The Reading Shelf

I’ve curated a selection of French Classics I deeply love — all available in beautiful English translations. I’m delighted to partner with Bookshop.org for this collection. Their mission to support independent booksellers aligns perfectly with the spirit of The Ritual of Reading. When you purchase through my affiliate link, I receive a small commission at no extra cost to you — a gesture that helps sustain this literary space and keeps the focus on mindful, meaningful reading.

You can explore the full collection here:

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.