France has always had a complicated relationship with its women—revolutionary in theory, maddeningly slow in practice. This is, after all, the country that gave the world Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in the same breath. The country where women couldn’t vote until 1944, couldn’t open a bank account without their husband’s permission until 1965, couldn’t wear trousers legally until 2013 (yes, you read that correctly—the ban was only officially repealed in 2013, though obviously unenforced for decades).

The French feminist story is one of fascinating contradictions: pioneers in women’s rights discourse who were simultaneously trapped by some of Europe’s most restrictive laws. Intellectually progressive salons where brilliant women held court, yet those same women needed a man’s signature to manage their own money. A literary culture that celebrated female writers, yet often dismissed them as frivolous or derivative compared to their male counterparts.

But here’s what makes French women authors so compelling: they didn’t wait for permission. They wrote anyway. They published under male names, they scandalized society, they chose unconventional lives, they claimed their own stories even when the law said those stories weren’t fully theirs to claim.

Throughout history, French women authors have left an indelible mark on literature not just through their writing, but through the lives they dared to live. They made choices that made them stand out, that made them controversial, that made them unforgettable. They understood something essential: that a woman who writes is already, by definition, claiming space that wasn’t freely given.

This autumn, as we watch the leaves turn and the light shift, I want to introduce you to five French women writers whose work deserves your attention—not as footnotes to male literary history, but as essential voices in their own right. These are women separated by centuries, yet connected by a common thread: the refusal to be silenced, the determination to write their truth, whatever the cost.

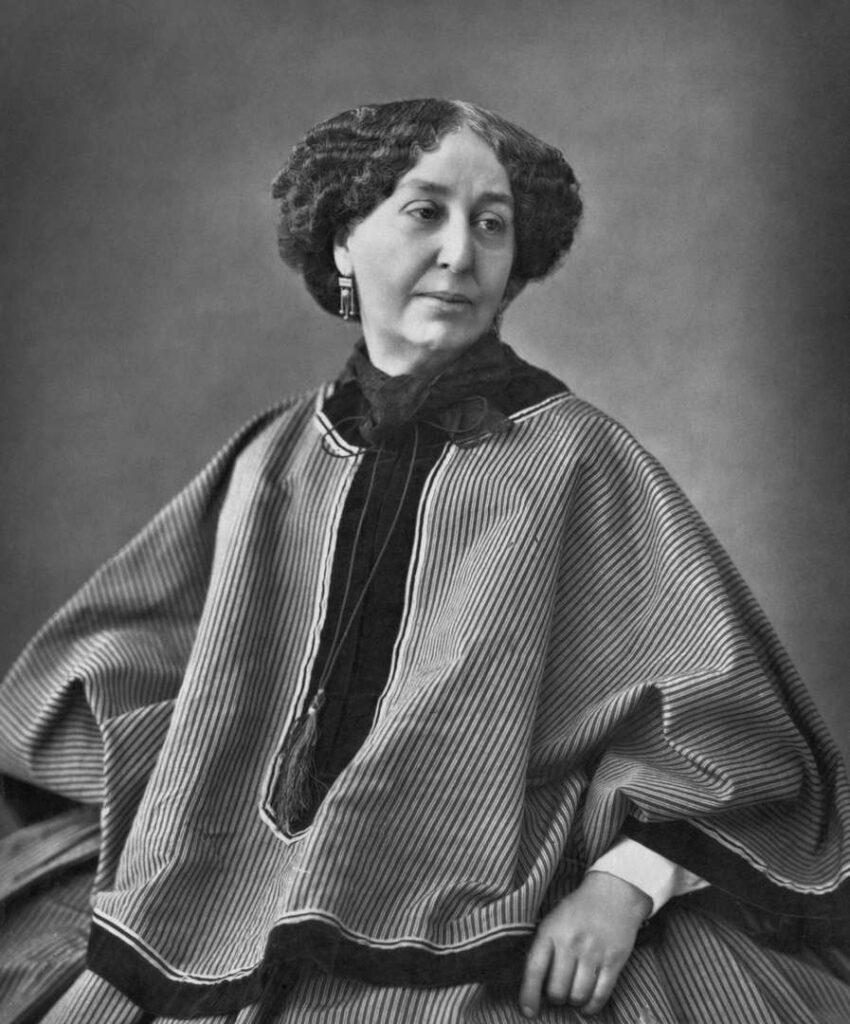

George Sand (1804-1876): The Woman Who Wore Trousers

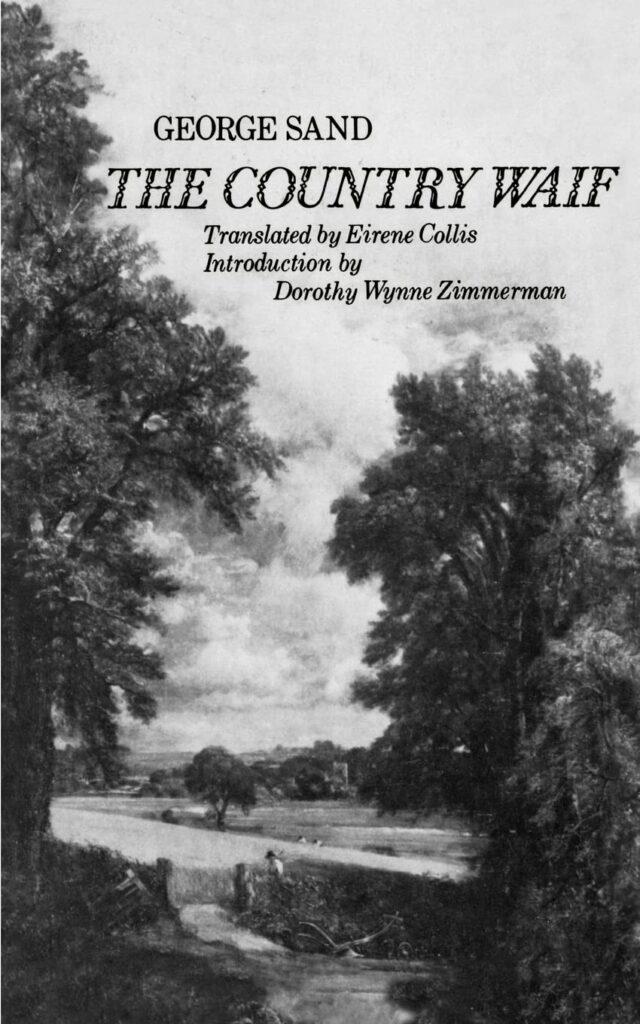

François le Champi / The Country Waif

Before there was George Eliot, before there were the Brontë sisters publishing under male pseudonyms, there was George Sand—Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin, who became one of the most prolific and celebrated writers of 19th-century France by the simple expedient of signing her work with a man’s name.

But calling her choice “simple” would be a profound misunderstanding. Sand didn’t just adopt a male pseudonym for publishing convenience. She wore men’s clothing to access theaters and spaces forbidden to women. She smoked cigars in public. She took lovers openly, scandalizing Parisian society. She divorced her husband in an era when divorce meant social death for women. She chose freedom over respectability, again and again, paying the price in gossip and scandal but never in silence.

What strikes me most about Sand isn’t the scandal, though—it’s the tenderness. Here was a woman who lived with such boldness, yet wrote with such gentle attention to the lives of ordinary people. While her contemporaries were chronicling Paris, Sand turned her gaze to the French countryside, to peasants and farmers, to matters of the soul rather than society drawing rooms.

François le Champi is quintessential Sand: the story of a foundling child raised by a miller’s wife, and the complicated love that develops between them as he grows to manhood. It’s a novel about rural life, about the rhythms of the countryside, about love that defies social categories.

Reading Sand now, I’m struck by how radical her empathy was. She didn’t need to make her characters sophisticated to make them worthy of literature. She understood that a miller’s wife could have as rich an emotional life as any Parisian lady, that a foundling could carry as much dignity as any nobleman. In an era obsessed with social hierarchy, this was quietly revolutionary.

Sand wrote over seventy novels, countless essays, and twenty-five volumes of autobiography. She corresponded with everyone from Flaubert to Dostoevsky. She hosted Chopin and Liszt at her country estate. She lived exactly as she pleased, and she wrote exactly what she wanted to write. Start with François le Champi, and you’ll understand why Flaubert called her “a great man.”

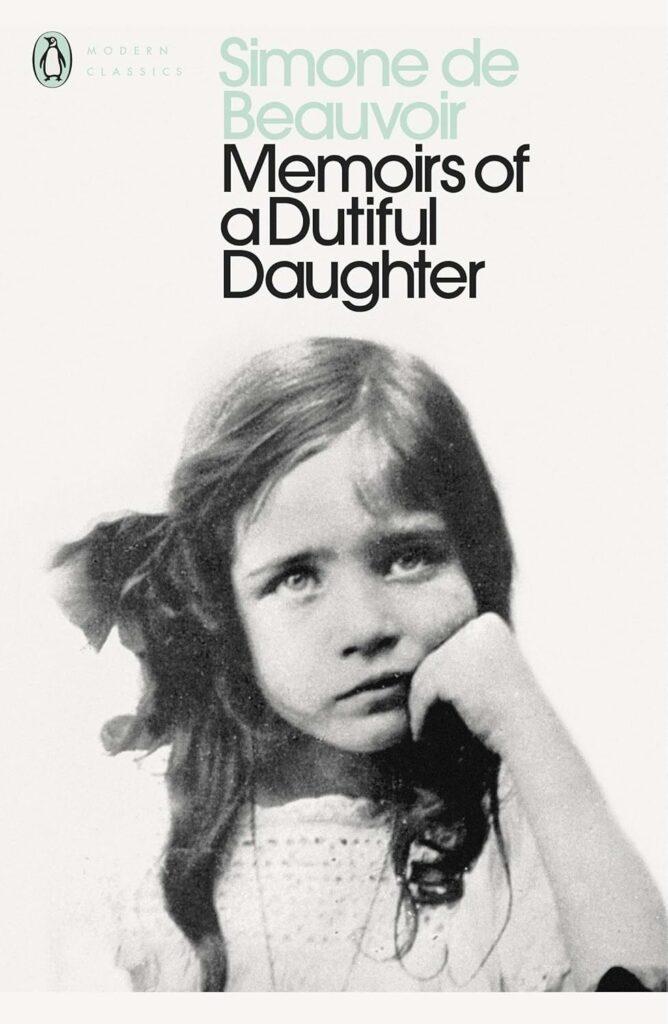

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986): The Rebel Scholar

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter

If George Sand scandalized the 19th century, Simone de Beauvoir rewrote the intellectual landscape of the 20th. Philosopher, novelist, essayist, feminist icon—and always, always, complicated.

The story most people know about Beauvoir is her relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre: the famous pact they made never to marry, to maintain separate apartments, to allow each other complete freedom. It’s a story that both elevated her—as a woman who refused conventional domesticity—and diminished her, as if her philosophical work was somehow secondary to her role as Sartre’s companion. Even now, half a century after The Second Sex revolutionized feminist thought, Beauvoir lives slightly in the shadow of “a great man.”

This is the paradox at the heart of Beauvoir’s life: a woman who wrote the definitive text on women’s oppression, yet whose own brilliance was perpetually measured against her male partner. Who theorized women’s freedom, yet whose choices were endlessly scrutinized and judged. Who declared “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” yet couldn’t fully escape being defined by her relationship to a man.

Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter takes us back to the beginning, before Sartre, before fame, before philosophy. It’s the story of her childhood and adolescence in bourgeois Paris, her intellectual awakening, her gradual rebellion against everything she was raised to be. The “dutiful daughter” of the title is both who she was and who she refused to remain.

What I love about this memoir is how honestly Beauvoir examines her own formation. She doesn’t present herself as naturally rebellious or innately feminist. She shows us the slow process of waking up, of questioning, of choosing to become someone different from what her family and society expected. She was dutiful, until she decided she wouldn’t be anymore.

Reading Beauvoir now, I’m less interested in her relationship with Sartre than in her relationship with herself: how she forged an intellectual life against enormous odds, how she claimed the right to think and write and be taken seriously.

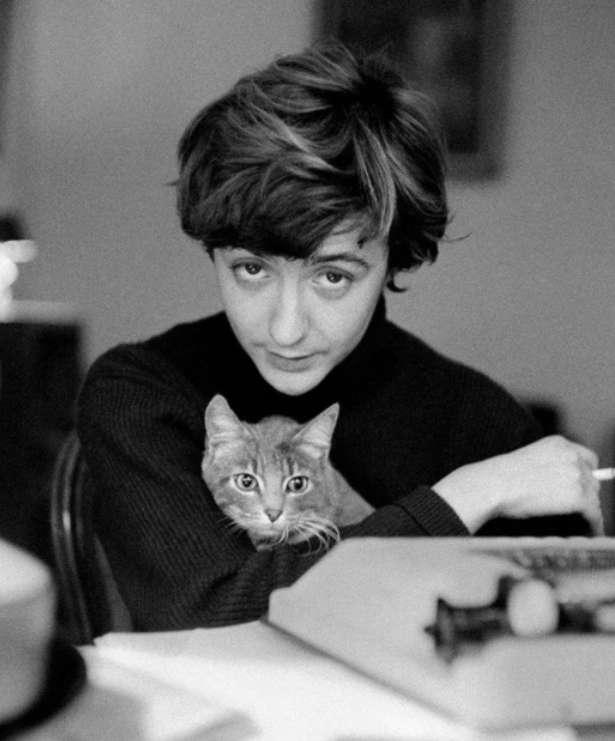

Françoise Sagan (1935-2004): The Night Queen of Paris

A Certain Smile or Aimez-vous Brahms…

Françoise Sagan published Bonjour Tristesse at eighteen and became an instant sensation—and an instant scandal. The novel, about a cynical teenager who sabotages her father’s relationship, was called immoral, corrupting, dangerous. Critics dismissed it as frivolous. The literary establishment clutched its pearls.

Sagan didn’t care. She bought a Jaguar with her earnings and crashed it. She gambled in casinos, attended every party, lived the life of Parisian nightlife excess. She wrote quickly, seemingly effortlessly, publishing novel after novel that the critics continued to dismiss as “easy literature”—as if clarity and readability were flaws rather than achievements.

Here’s what I’ve learned about Sagan: the critics were wrong. They mistook her lightness of touch for lightness of substance, her elegant simplicity for simplicity of thought. They couldn’t see past the glamorous persona to recognize what she was actually doing—creating perfect, precise snapshots of Parisian society, capturing the emotional lives of people who appeared sophisticated but were, underneath it all, desperately lonely.

For me, there isn’t a more Parisian read than a Sagan novel. Not Balzac’s grand social architecture, not Zola’s sweeping naturalism, but Sagan’s intimate portraits of beautiful people in beautiful apartments having beautiful affairs and feeling, despite everything, empty. She understood post-war Paris in a way no one else did—the glamour that was also desperation, the freedom that was also aimlessness, the modernity that left people unmoored.

A Certain Smile follows a young woman’s affair with an older man, her boyfriend’s uncle. It’s spare, elegant, devastating. Sagan captures the exact emotional tenor of an affair that feels like liberation but is actually another kind of prison—the prison of being young and female and available, of mistaking attention for love, of learning that desire isn’t the same as happiness.

Aimez-vous Brahms… is even more achingly beautiful. It’s about a woman in her late thirties, her affair with a younger man, and the terrible awareness that time is passing. The title comes from a moment in a nightclub when someone asks if she likes Brahms, and it becomes a kind of code—do you like old things, classical things, are you ready to admit you’re aging?

Start with either of these novels on an autumn evening when the light is fading and Paris feels very far away—or very close, depending on where you are and what you’re longing for. Let Sagan take you to cafés and apartments and nightclubs where everyone is beautiful and sad and trying so hard to feel something real. Let her show you that “easy literature” can cut right to the heart of things, that simplicity is its own kind of sophistication.

A Certain Smile

🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A short note on how and why I share book links

Aimez-vous Brahms

🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A short note on how and why I share book links

Muriel Barbery (b. 1969): The Poet of Contemporary Paris

The Gourmet Rhapsody

While Sagan captured mid-century Paris, Muriel Barbery captures something more elusive: contemporary Paris as a dream, a meditation, a floating essence above the city streets. Her novels don’t walk through Paris—they drift above it, catching its volatile spirit in carefully chosen words.

I need to be honest with you: my love of Muriel Barbery begins and ends with her language. Barbery writes what I consider the most beautiful version of contemporary French. Her prose has a particular quality, almost musical, where each word feels inevitable yet surprising. Reading her in French is like listening to someone play an instrument they’ve mastered so completely that the technique becomes invisible, leaving only the pure expression of thought and feeling.

Gourmet Rhapsody (Une gourmandise in French) is about a food critic dying, trying to remember one perfect taste from his past. It’s a slim novel, more novella than sprawling epic, but within its pages Barbery creates an entire philosophy of taste, memory, and beauty. Each chapter is a different remembered flavor—oysters, pastries, tea—and each becomes a meditation on life itself.

Reading Barbery requires a particular state of mind. You can’t rush her. You have to slow down, pay attention to the language itself, let the sentences work their quiet magic. She’s not for everyone—her deliberate pace, her philosophical bent, her preference for interiority over action—but if you’re in the right mood, she’s transcendent.

Read Gourmet Rhapsody on an autumn afternoon with good coffee and excellent pastries nearby. Let Barbery remind you that paying attention—to taste, to beauty, to the precise quality of light and thought—is its own kind of revolution. Let her show you that contemporary French literature can be as gorgeous and demanding as any classic, that language itself can be a destination. (I dedicated a whole article to this novel, you can read it and watch the YouTube video by clicking here)

Clara Dupont-Monod (b. 1973): The Journalist’s Eye, The Novelist’s Heart

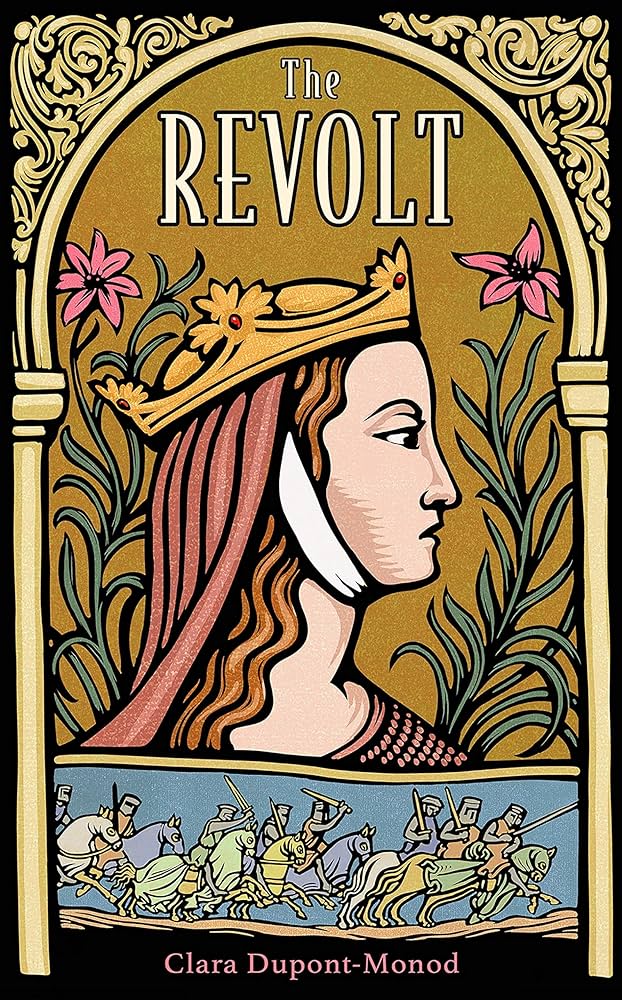

The Revolt

If you’re a historical fiction reader who wishes more French contemporary authors were translated into English, Clara Dupont-Monod is your answer. She’s a journalist who brings a reporter’s eye for detail and a novelist’s gift for emotional truth to historical fiction. That combination—the precision of journalism, the research of a serious historical novelist, the prose of someone who understands that beauty and accuracy aren’t enemies—makes her work utterly distinctive.

The Revolt (La Révolte in French) is her take on one of history’s most dramatic family conflicts: the attempt by Henry II Plantagenet’s sons to overthrow their father, orchestrated by none other than Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Eleanor. My beloved Aliénor. The Duchess of Aquitaine who became Queen of France, then Queen of England, who went on Crusade, who bore ten children, who spent sixteen years imprisoned by her husband, who outlived all but two of her children and died at eighty-two having shaped the political landscape of Europe for nearly a century. If ever there was a woman who refused to be silent, it was Eleanor.

Dupont-Monod brings Eleanor to life not as the mythologized queen of historical romance, but as a complex political actor, a mother navigating impossible choices, a woman wielding what power she could in a world that wanted to contain her. She understands medieval politics deeply enough to make the power struggles feel real and urgent, but she never loses sight of the human beings caught in these grand historical movements.

For readers who love Sharon Kay Penman, Hilary Mantel, or other historically rigorous novelists, Dupont-Monod will feel like coming home—but with a distinctly French sensibility. Her prose is elegant without being ornate, her pacing deliberate but never sluggish, her attention to detail meticulous but never overwhelming.

Read The Revolt when you want to be transported not just to another place but to another time, when you want history to feel alive rather than distant, when you want to meet Eleanor of Aquitaine again and see her through fresh, French eyes. Let Dupont-Monod show you that historical fiction can be both intellectually serious and deeply moving, that scholarship and storytelling aren’t opposed but complementary.

Installation at the Château de Chaumont-sur-Loire

The Thread That Connects Them

Five women, separated by centuries and circumstance, yet connected by something essential: the determination to write their own stories in a country that was both ahead of and behind its time on women’s rights. What strikes me, reading these women together, is how each had to negotiate her relationship to French literary culture differently. Sand had to become “George” to be taken seriously. Beauvoir had to live in Sartre’s shadow even as she produced work as significant as his. Sagan had to endure being dismissed as frivolous. Barbery has to resist the contemporary pressure for plot-driven narratives that leave no room for linguistic beauty. Dupont-Monod has to navigate a literary culture that sometimes looks down on historical fiction as less “serious” than contemporary realism.

But they all persisted. They all found ways to write what they needed to write, to say what they needed to say. They understood that being a woman writer in France meant being always slightly in opposition—to tradition, to expectation, to the male-dominated canon. And they wrote anyway.

An Invitation to Autumn Reading

This autumn, as you settle into shorter days and longer nights, as you pull out your favorite blanket and brew your favorite tea, consider spending time with these women. They have different things to offer—Sand’s countryside tenderness, Beauvoir’s intellectual rigor, Sagan’s Parisian glamour, Barbery’s linguistic beauty, Dupont-Monod’s historical sweep—but they’re all essential voices in French literature.

And here’s the wonderful thing: you don’t have to choose. You can create your own reading journey through French women’s literature, following your curiosity and your pleasure. Start with whichever author calls to you. If you love the countryside, begin with Sand. If you’re drawn to intellectual life, start with Beauvoir. If you want glamour and heartbreak, choose Sagan. If you crave beautiful language, pick up Barbery. If historical fiction is your passion, Dupont-Monod awaits.

These women didn’t write for posterity or academic study—they wrote because they had to, because silence was impossible, because the alternative was a kind of death. They wrote to tell us: you can refuse to be silent. You can claim your story. You can write your truth, whatever the cost.

This autumn, let them show you how.

What French women authors have shaped your reading life?

I’d love to hear about your favorites, or about the women writers—from any tradition—who’ve refused to be silent in your own reading journey.

Let’s continue the conversation in the comments

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.