Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 12

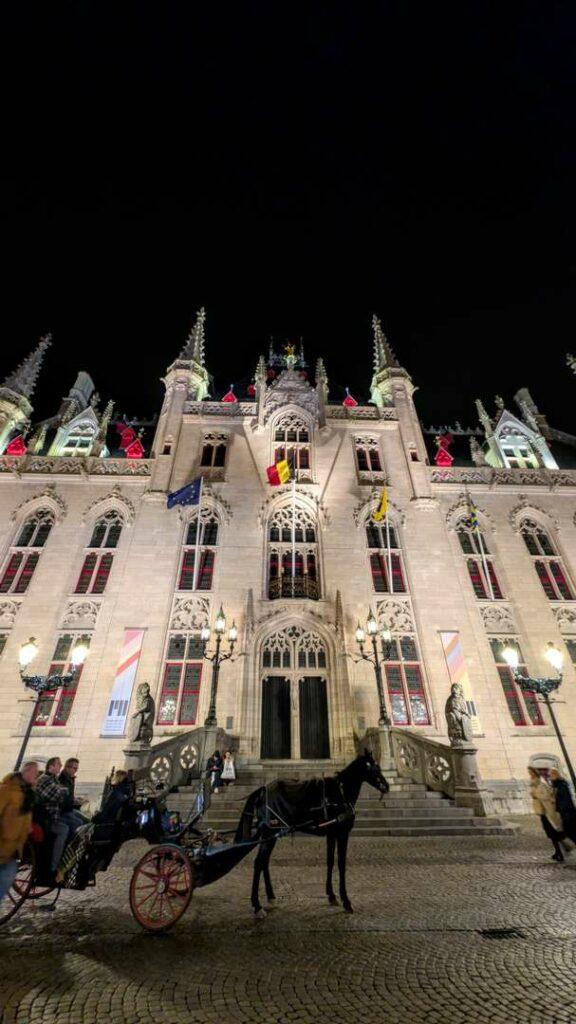

As I wandered through the Christmas market in Bruges, the air thick with the scent of mulled wine and roasting chestnuts, I heard people laughing everywhere. Couples doubled over at shared jokes, friends cackling at stories told in rapid-fire Dutch, children shrieking with delight at the carousel lights. And it struck me how particular laughter is—how humor might be one of the most subtle and difficult aspects of any foreign culture to truly grasp.

You can learn a language’s grammar, memorize its vocabulary, even master its regional peculiarities. But to understand what makes a people laugh? That requires something deeper. It’s about shared assumptions, cultural anxieties, the specific absurdities that a society has collectively agreed to find funny rather than tragic.

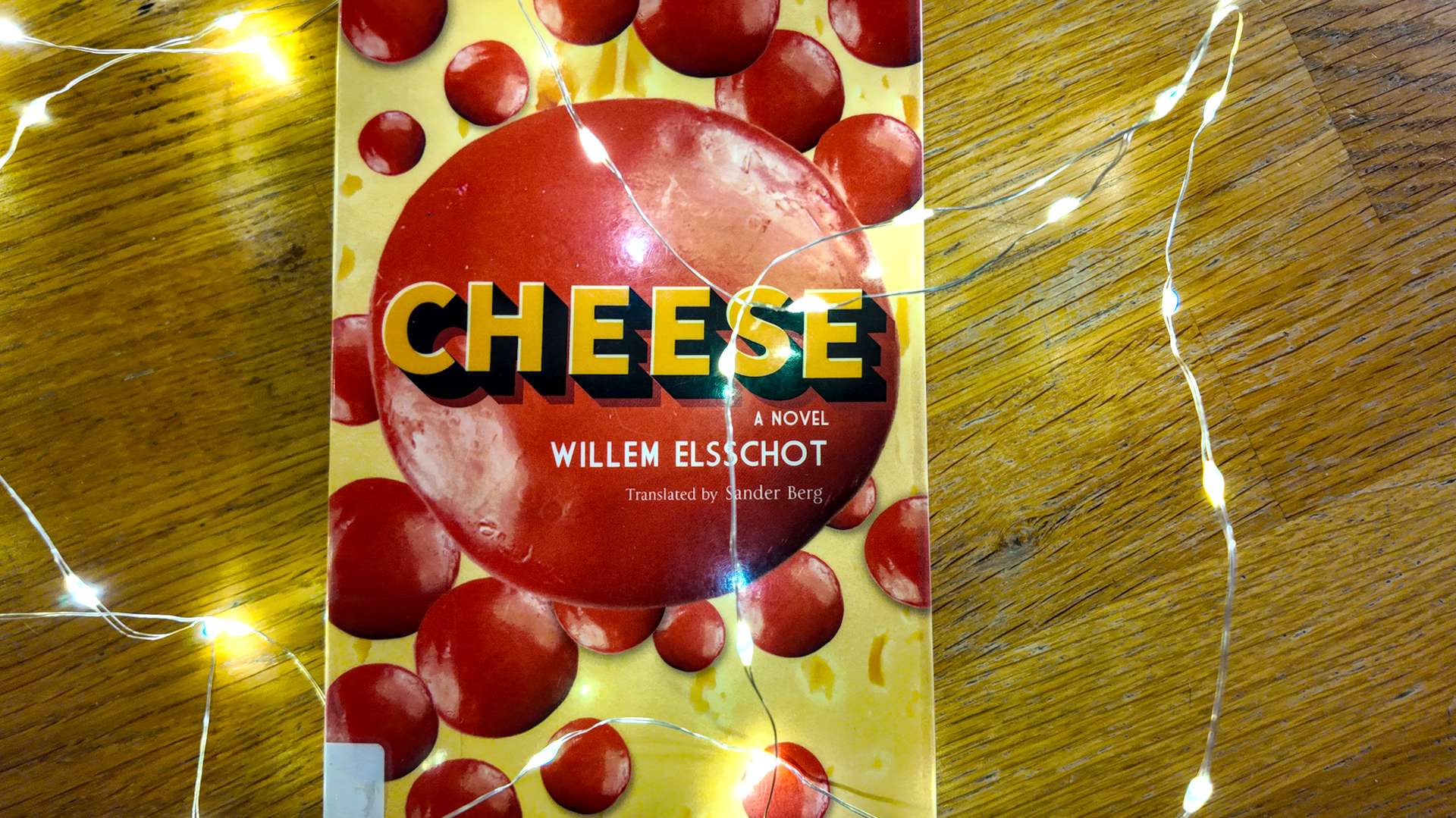

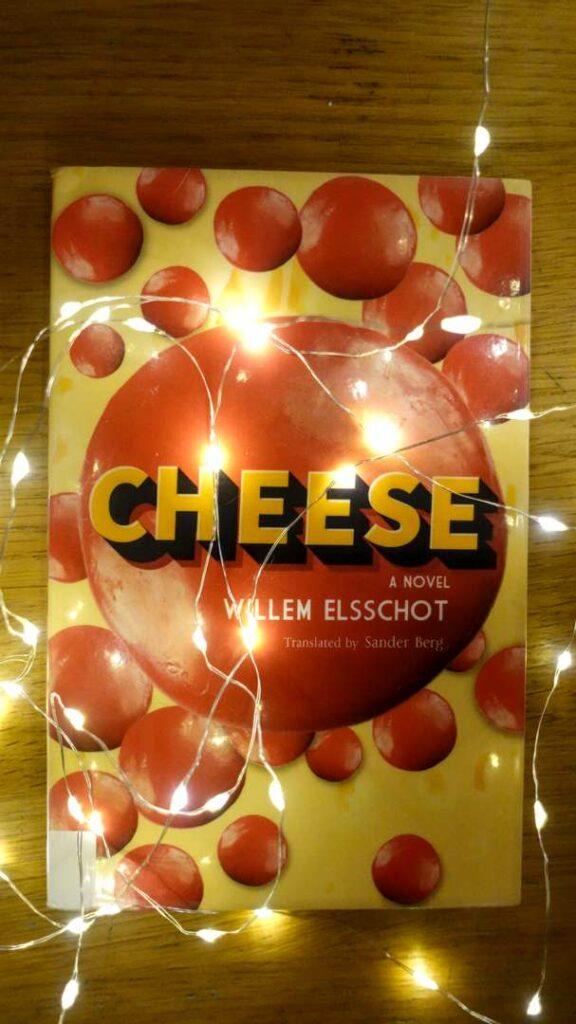

Reading satire, I’ve come to think, might be the best introduction to this mysterious territory. And I’m fortunate, because the most translated Flemish novel of all time happens to be a satire—a sharp, comic examination of the business world that has somehow conquered readers across cultures and languages. Willem Elsschot’s Cheese has traveled from its 1933 Antwerp origins to become a minor classic of European literature, translated into over forty languages. That’s no small feat for a novella about a failed cheese salesman.

The plot is deceptively simple. Frans Laarmans, a small-time office clerk living a comfortable if unremarkable life, is suddenly seized by entrepreneurial ambition. Van Schoonbeke, the wealthy friend of his brother—smooth-talking, confident, worldly—convinces him to become the exclusive Dutch cheese distributor for Belgium. It’s a sure thing, he assures him. The cheese practically sells itself. All Frans needs to do is set up an office, hire staff, and watch the money roll in.

So Frans does exactly that. He rents impressive office space. He hires employees. He orders business cards. He imagines himself transformed from clerk to merchant prince. And then the cheese arrives—ten thousand wheels of Edam, filling his warehouse, and almost immediately, absolutely nothing happens. No customers materialize. No orders arrive. The cheese sits, aging and increasingly pungent, while Frans watches his dreams curdle into financial catastrophe.

🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A short note on how and why I share book links

What makes Cheese remarkable isn’t just its premise, but how Elsschot tells it. This is a book with pronounced self-irony—a quality that, I’m beginning to notice, runs deep in Belgian culture. Both the Flemish and Walloon writers I’ve explored so far have an eye for the sharp ironies of life, and they’re quite unforgiving in underlining them. But what distinguishes Elsschot is how he does this through humor rather than bitterness.

The comedy here is observational, almost anthropological. Elsschot watches Frans with the detached amusement of someone who understands exactly how self-delusion works, who recognizes the gap between how we imagine ourselves and who we actually are. Frans isn’t a villain or even particularly foolish—he’s simply human, susceptible to flattery and fantasy, wanting to believe he’s capable of more than his circumstances suggest.

Reading it in translation, I found myself marveling at how the humor survived the journey from Dutch to English. Humor is notoriously difficult to translate—it’s so dependent on rhythm, on the specific music of a language, on cultural references that don’t always cross borders. Yet Cheese reads with an effortless lightness in English, the comedy intact, the ironies still sharp.

Perhaps that’s because Elsschot’s satire targets something universal: the eternal human capacity for self-deception, the way we construct elaborate fantasies around our own potential, the gap between the life we imagine and the life we’re actually living. Every culture has its Frans Laarmans—the person who mistakes a single opportunity for destiny, who confuses activity with achievement, who learns too late that confidence isn’t the same as competence.

But there’s also something specifically Belgian in the novel’s sensibility. It’s refreshing to encounter this irony in humorous form, because—and I’ll be honest here—there are several books I started reading for this project that never made it to my list, books you’ll never hear me mention, since I make it a point never to give non-recommendations. But I’ve noticed that Belgian irony can sometimes tip toward the heavy side, can become almost punishing in its insistence on life’s cruelties and disappointments.

Humor, I think, makes everything more subtle. It creates distance without coldness, allows for criticism without cruelty. Elsschot could have written a bitter takedown of capitalism, ambition, and masculine ego. Instead, he wrote something gentler and somehow more devastating—a comedy that acknowledges the ridiculousness of human aspiration while never quite losing sympathy for the aspirant.

The novel doesn’t offer redemption or transformation. Frans doesn’t learn some profound lesson or emerge wiser from his ordeal. He simply returns to his clerk’s desk, a little poorer, a little more cautious, having briefly glimpsed a life he was never quite suited for.

In the end, Cheese is a small masterpiece of deflation—of ambitions deflated, egos deflated, dreams deflated like balloons slowly losing air. It’s funny because it’s true, and it’s true because Elsschot understands that most of our failures aren’t dramatic. They’re just embarrassing, expensive, and ultimately survivable. We imagine ourselves as tragic heroes and discover we’re merely comic characters in someone else’s story about the cheese business.

And perhaps that’s the real Belgian sensibility I’m discovering in this advent calendar journey—this ability to look at life’s humiliations with clear eyes and a wry smile, to acknowledge disappointment without descending into despair, to laugh at ourselves before anyone else gets the chance.

See you tomorrow for another stop on this literary journey through Belgium.

Until then, Merry Advent!

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 12th |

| Dear Friend, When was the last time you laughed the way you did as a child? Not the polite chuckle we offer in meetings, not the knowing laugh at a clever satire. I mean that pure, uncomplicated delight—laughter that bubbles up without irony, without analysis, without the protective layers we’ve built around our joy. I’ve been thinking about this because today I found myself considering not novels or poetry, but small blue creatures who live in mushroom houses and speak a language where nearly every noun has been replaced by the word “smurf.” The Smurfs. Or as they’re known in their native French, Les Schtroumpfs—a word that sounds exactly like what it describes, nonsensical and perfect. Created by Belgian cartoonist Peyo in 1958, they were originally side characters before they colonized the imagination of children worldwide. I have only a handful of memories of watching the Smurfs on television when I was little. We didn’t have regular access to the show, so catching an episode felt like stumbling upon something precious. And every time I did—Papa Smurf with his red cap, Smurfette with her blonde hair, Grouchy with his eternal complaints—it felt like Christmas. There was such a lightness in their adventures. Yes, Gargamel was always scheming. Yes, there were problems to solve. But somehow, it never felt heavy. The stakes were manageable. The world was small enough to understand and kind enough to live in. I wonder if that’s what we lose as we grow up—not the ability to laugh, but the ability to laugh without qualification. Adult humor so often requires context, requires us to understand what we’re laughing at. We’ve become sophisticated in our amusement, which is another way of saying we’ve become complicated in our joy. Children don’t laugh at irony. They laugh at silly voices and pratfalls and the sheer absurdity of a cat chasing creatures who are “three apples high.” They laugh because something delights them, full stop. No analysis required. Belgium gave us this gift—this little pocket of lightness in a world that can be so heavy. And isn’t that something to be grateful for? Not every cultural export needs to be profound or challenging. Sometimes a culture’s greatest gift is permission to simply delight in something ridiculous. Maybe that’s what I’m really grateful for this evening—a reminder that before we learned to laugh at irony and appreciate satire, we knew how to laugh at something simply because it made us happy. Because it was silly and colorful and invited us into a world where even the grumpiest Smurf was still fundamentally part of the village. So here’s to Belgium, and to Peyo, and to every artist who has created something whose only ambition is delight. May we all remember, occasionally, how to laugh like we did when three apples high seemed like a perfectly reasonable unit of measurement. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.