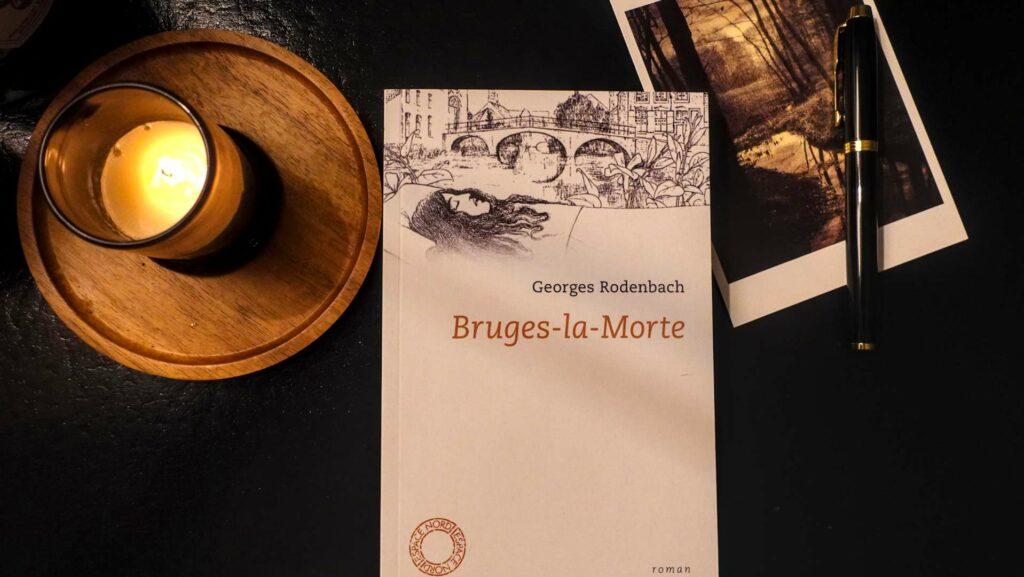

Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 4

“Every town is a state of mind, a mood which, after only a short stay, communicates itself, spreads to us in an effluvium which impregnates us, which we absorb with the very air.”

— Georges Rodenbach, Bruges-la-Morte

Diving into a symbolist novel, even a short one, is an act of bravery. I’ll admit it freely: I need to be motivated by something other than literature itself when facing certain genres. And for this classic of Belgian letters, the city of Bruges became my portal—my reason to persist, my invitation to begin.

So with the book in hand, I took my time. Late at night, when the city streets finally exhale after the day’s tide of tourists has receded, I met Georges Rodenbach in front of the Rosary Quay—one of the most photographed spots in Bruges, and the very place he chose as the residence of his protagonist. The water was still. The lamps glowed softly against the stone. And in that quiet, I could almost hear what he was trying to say.

Born in Tournai to a French mother and a German father, Rodenbach studied law in Ghent but carried throughout his life a nostalgic attachment to the quiet Flemish towns of his childhood—the ones that time seemed to have forgotten, or at least agreed to leave alone for a while. His most notable work, this slender novel Bruges-la-Morte, is considered the archetypal symbolist text. And as such, the plot itself is rather simple.

A short note on how and why I share book links

A widower named Hugues Viane has retreated to Bruges, seeking in its muted streets and silent canals a reflection of his grief. The city becomes his accomplice in mourning, its stillness a kind of shrine to his dead wife. But when he encounters a young actress who bears an uncanny resemblance to the woman he lost, his carefully preserved sorrow begins to unravel. What follows is an obsessive, increasingly unhinged attempt to resurrect the past—through imitation, through delusion, through a love that is less romance than haunting.

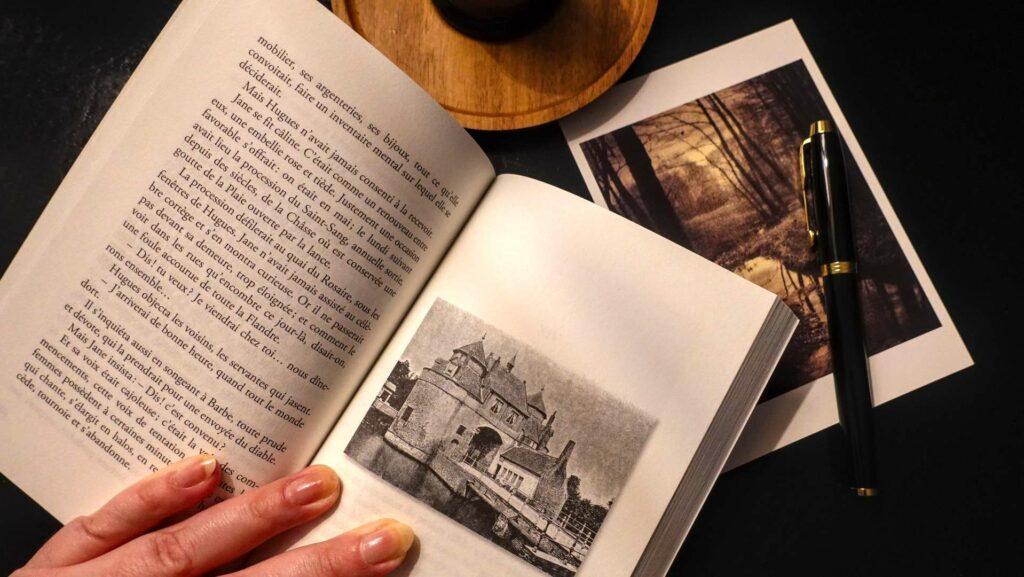

And here’s something quietly revolutionary: Bruges-la-Morte is said to be the first work of fiction ever illustrated with photographs. Not sketches or engravings, but actual photographs of Bruges—its bridges, its belfry, its canals—woven into the text as though the city itself were co-author. Rodenbach wanted readers to see what his character saw, to feel the weight of stone and water pressing against the narrative. I found a copy of the original edition, photographs and all, in a museum shop in Brussels. Pure luck. I held it carefully, turning each page like an artifact, marveling at how ahead of its time this little book truly was.

I wandered the streets he described. I entered the cathedrals, admired the canals drenched in moonlight. And while I can safely say that his Bruges no longer exists—the very success of his novel brought a flood of tourism that forever changed the city’s European destiny—the book is still filled with beautiful turns of phrase, landscapes sketched entirely by feeling, a delicacy that lingers even when the subject matter grows heavy.

Rodenbach declared openly that his intention was to make the city the main character of the story—to create a narrative that doesn’t simply happen in Bruges, but that is shaped by the energy and vibration of the city itself. The fog, the bells, the water: all of them co-conspirators. And that alone is worth the effort of navigating his character’s obsessive grief, which, in all honesty, required real stamina from me as a reader.

But the language—the language is beautiful. Phrases like this one stopped me cold:

“It is precisely resemblance that reconciles habit and novelty, balancing them out, fusing them at some indefinite point, acting as their horizon line.”

These are the kinds of sentences that justify the journey, even through darkness.

In the end, I believe this read has been essential to my understanding of something fundamentally Flemish in feeling and sensibility. Not every book needs to win your heart to teach you something true. Sometimes a novel offers you a key to a culture, a way of seeing that you wouldn’t have found on your own. Bruges-la-Morte gave me that: a glimpse into the melancholic undercurrent that runs through so much of Flemish art and thought, the way beauty and sorrow can occupy the same space without contradiction.

I’m only at the beginning of this literary journey, and already it announces itself as more subtle and surprising than I would have thought. With each book I finish, the puzzle looks both more chaotic and closer to a finished picture.

Tomorrow, we step away from the page and into the warmth of the kitchen—because December in Belgium wouldn’t be complete without honoring a certain kind-hearted saint and the sweetness that arrives in his name. There will be spices, there will be butter, there will be a recipe passed down like a secret.

So come back tomorrow. I’ll be here, dusting flour from my hands, waiting by candlelight.

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 4th |

| Dear Friend, There’s a particular kind of discomfort that comes from reading something that resists you—not because it’s poorly written, but because it asks you to sit with feelings you’d rather not entertain. Bruges-la-Morte was that book for me. Hugues Viane’s obsessive grief, his unraveling devotion to a dead woman, his increasingly unhinged attempt to resurrect the past through a living substitute—none of it felt like territory I wanted to occupy. The atmosphere was somber, decidedly morbid. I felt sorry for him in the way you feel sorry for someone who won’t let you help them. And I made a real effort not to empathize, because empathy felt dangerous here—like it might pull me into his fog and never let me out. But I kept reading. Partly for this project, yes—but also because something else was happening beneath my resistance. I was learning to hold discomfort without needing to resolve it immediately into I like this or I don’t like this. I was discovering a kind of detachment I’d been searching for without knowing it—the ability to see the bigger picture, to appreciate craft and intention and cultural truth even when the emotional landscape felt inhospitable. And somewhere in that uncomfortable space, I grew. Not despite the darkness of the novel, but becauseof it. Because growth, I’m learning, rarely happens in comfort. It happens when we stay with something that challenges us, when we stop asking art to make us feel good and start asking it to make us see differently. Rodenbach’s Bruges taught me that beauty and sorrow can occupy the same space without contradiction. But more than that, it taught me that I can occupy that space too—observing, understanding, even admiring—without needing to love it, without needing to turn away. Maybe that’s what maturity in reading looks like: not the absence of preferences, but the presence of patience. The willingness to sit in the grey. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.