Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 8

There’s a particular tyranny in the modern insistence that solitude is something to be cured. We’re told constantly that connection is wellness, that community is health, that choosing one’s own company over others’ is a red flag for depression or antisocial tendencies. The introvert has become a diagnostic category. The person who declines an invitation is someone to worry about.

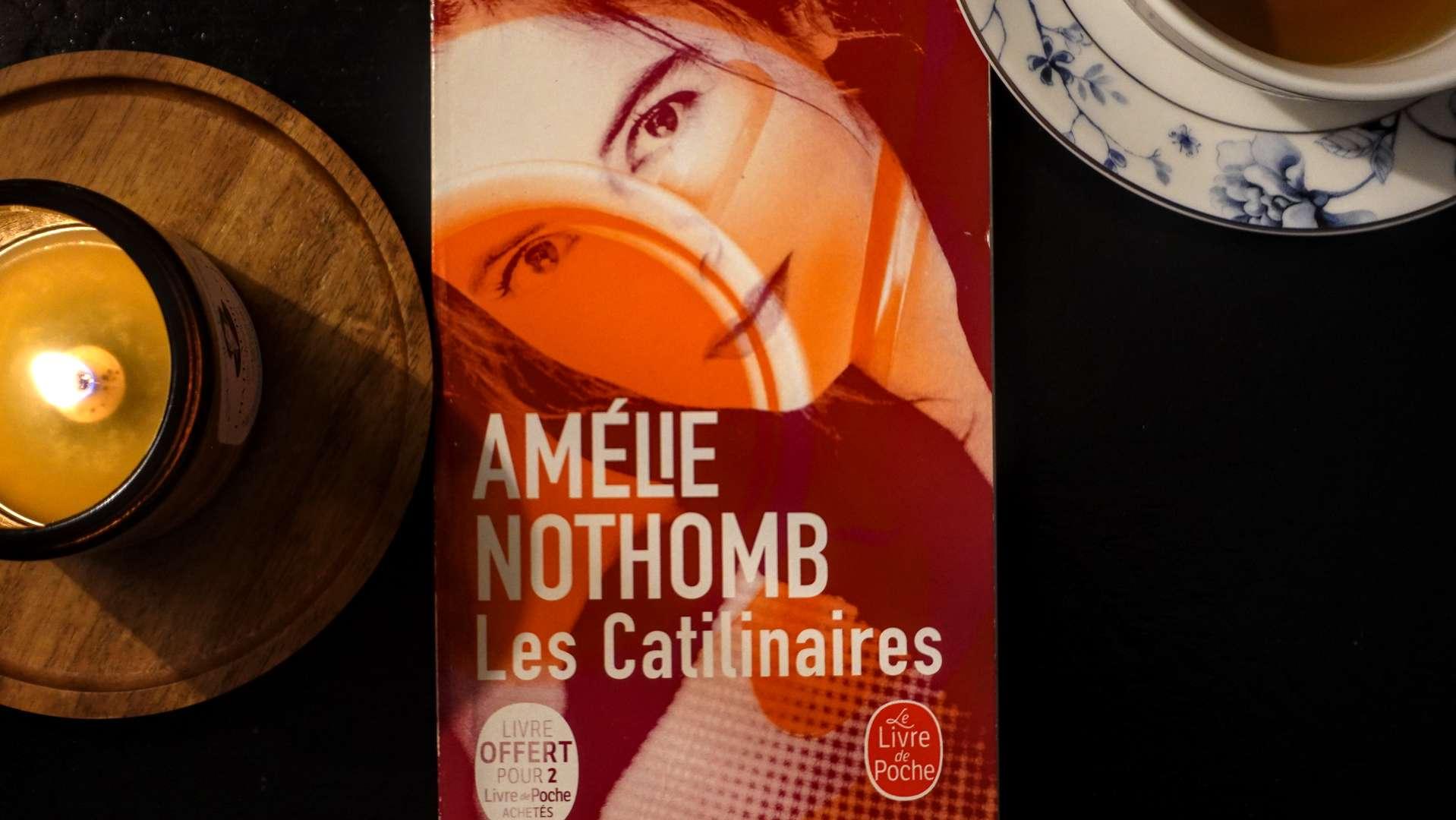

Amélie Nothomb’s Les Catilinaires (translated as The Stranger Next Door) takes this social pressure and amplifies it into nightmare. I’ll confess: I resisted Nothomb for years. Her prolific output, her theatrical public persona, her particular brand of Belgian Gothic whimsy—none of it felt like it was written for me. But this slim novel, with its claustrophobic examination of invasion of privacy, felt as though she’d reached directly into my own anxieties and given them literary form.

The premise is deceptively simple. Émile and Juliette, a retired couple, have moved to a remote house in the countryside to live out their days in peaceful solitude. They read, they tend their garden, they exist in the quiet rhythms of two people who have chosen each other and need no one else. Then one day, their neighbor—Palamède Bernardin—comes to visit. And he never leaves.

Not literally, of course. Palamède returns to his own home each evening. But every day at three o’clock, he arrives. He sits in Émile and Juliette’s living room. They drink the coffee that hospitality demands be offered. They talk about nothing—or rather, the hosts talk while Palamède sits in near-silence, a ghostly presence. And Émile and Juliette, trapped by the unspoken rules of civility, endure.

Nothomb understands something profound here: that politeness can be a prison. That the social contract we all implicitly agree to—be kind, be welcoming, don’t hurt others’ feelings—can become a weapon in the hands of someone willing to exploit it. Palamède Bernardin is not evil in any conventional sense. He’s simply impervious to hints, immune to social cues, and apparently without any understanding that his presence might not be desired. He is the embodiment of every boundary violation disguised as friendliness.

What makes Les Catilinaires so unsettling is how it captures the specific guilt that comes with wanting to be left alone. Émile and Juliette aren’t misanthropes. They don’t hate people. They simply want to live their own lives, in their own space, on their own terms. But this desire, which should be the most basic of human rights, becomes something they must defend, must justify, must feel obscurely ashamed of. When Émile finally explodes in anger at their unwanted visitor, we feel his rage—but we also feel his guilt, the nagging sense that perhaps he’s being cruel, unreasonable, that surely he should be able to tolerate a few hours of company each day.

The novel’s title references Cicero’s speeches against Catiline, the Roman senator who conspired against the Republic. Cicero’s opening salvo—”How long, Catiline, will you abuse our patience?”—echoes through Nothomb’s text. But here, the conspiracy is subtler. It’s the slow invasion of one’s peace, the colonization of one’s time, the assumption that anyone’s company is better than one’s own.

Nothomb writes with a precision that borders on the surgical. Her prose is clean, almost sparse, which makes the absurdity of the situation stand out in sharp relief. There’s dark comedy here, but it’s the kind that makes you laugh while simultaneously feeling a crawling discomfort. The book can be read in a single sitting—it’s barely over a hundred pages—but its brevity is part of its power.

I can’t say I’ve become a devoted Nothomb reader based on this one book.. But Les Catilinaires spoke to something I recognize: the experience of having your boundaries tested, of being made to feel selfish for wanting control over your own life, of the exhaustion that comes from performing sociability when what you crave is silence.

In our current moment, when loneliness is treated as an epidemic and solitude as its symptom, this novel feels almost like a manifest. It dares to suggest that sometimes, the problem isn’t that we’re alone—it’s that we’re not allowed to be. That the real cruelty isn’t in choosing solitude, but in refusing to respect someone else’s choice of it. That privacy isn’t a luxury or a character flaw, but a fundamental human need.

The ending, which I won’t spoil, offers a kind of liberation—though whether it’s triumphant or tragic depends on your perspective. What stays with me is the central question the novel poses: Why must we constantly justify our desire to be left alone? Why is the hermit suspect, the recluse pitiable, the person who declines company somehow incomplete?

Nothomb doesn’t answer these questions so much as she dramatizes their urgency. In doing so, she’s written a strange little book that feels like permission—permission to close the door, to decline the invitation, to choose your own company without apology. In a world that insists we’re only whole when connected to others, Les Catilinaires makes a case for the radical act of disconnection. Sometimes, the stranger next door is the one who won’t acknowledge that next door is exactly where they should stay.

See you tomorrow for a visit to one of Brussels hidden jewels !

Until then, Merry Advent !

During the 2025 Advent season, each post on The Ritual of Reading was accompanied by a Daily Advent Letter, sent privately to subscribers. These letters echo the theme of the article, but take a more personal and reflective path — closer to the hesitations, intuitions, and emotions that accompanied the writing.

What follows is the Daily Advent Letter that was written alongside this post.

| December 8th |

| Dear Friend, When was the last time you heard someone talk about respect? Not tolerance—we speak endlessly about tolerance. Not acceptance, not inclusion, not understanding. Those words have become the currency of contemporary discourse. But respect? The word itself has begun to sound almost quaint, like something your grandmother would say, a relic from an era when people wore hats and said “please” and “thank you” without irony. Reading Nothomb this week, I found myself returning to it again and again. Respect. The simple, radical act of respecting someone’s boundaries. Their privacy. Their right to say no without explanation. Their choice to live differently than you would choose for them. Somewhere along the way, we stopped teaching respect and started teaching commentary. We’ve become fluent in having opinions about other people’s lives—how they spend their time, whom they spend it with, what they choose to do with their solitude. The person who wants to be alone is depressed. The one who declines invitations is antisocial. The one who sets boundaries is difficult. Even those of us who still hold respect as a core value seem reluctant to name it. Perhaps because it sounds judgmental to suggest someone isn’t being respectful. Perhaps because respect implies distance, and we’ve been taught that distance is the opposite of love, when sometimes it’s the purest expression of it. Respect doesn’t ask you to understand someone’s choices. It doesn’t require you to agree with how they live. It simply asks you to acknowledge their right to make those choices without your intervention, your judgment, or your unsolicited presence. It’s the difference between tolerance and respect that strikes me most. Tolerance says: I’ll put up with you. Respect says: I see you as sovereign over your own life. Tolerance is gritted teeth. Respect is an open hand that doesn’t grasp. I wonder what the world would look like if we made respect—real, active, boundary-honoring respect—the value we promoted above all others in the years to come. Not just respect for identities or beliefs, but respect for the smaller, quieter choices: the right to privacy, to solitude, to live a life that doesn’t require constant justification or performance. Maybe the most respectful thing you can do for another person is simply to let them be. Until tomorrow, Alexandra |

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.