Austrian Advent Calendar Day 21

Hello, dear friends, and welcome to our winter solstice episode! If you’ve been following these Advent reflections for any time, you already know I hold particular affection for this symbolic evening. The longest night of the year offers me a moment of profound comfort, as though the universe itself were granting permission to simply be—to exist without the pressure of efficiency or productivity, to rest in the darkness rather than rushing to escape it.

I found myself wondering what Austrian subject would be most appropriate for the winter solstice, and discovered the answer while reading—naturally. For me, the solstice and winter in general represent the season for retreating into my cozy kingdom. Time spent at home ranks among my greatest luxuries, and I was intrigued to learn that during Austria’s COVID lockdown, commentators compared the experience to a second Biedermeier age, since that earlier era was the “at home” period par excellence in Austrian history. I researched, found the perfect book, ordered it from my beloved secondhand book website, and dove in with complete absorption.

The Biedermeier was an era in Central Europe spanning 1815 to 1848—those crucial decades between the Congress of Vienna and the Revolutions of 1848—that witnessed the middle classes growing in number, prosperity, and cultural influence. These thirty-three years represented a time of political stability in the Austrian Empire, maintained through the conservative and somewhat repressive rule of Chancellor Klemens von Metternich. While political subjects faced heavy censorship and public discourse was carefully controlled, society received encouragement—even pressure—to focus on domestic aspects of life. And so artists and citizens alike turned their attention to everything non-conflicting with the political order: dancing, music, country life, interior decorating, family gatherings, the cultivation of private rather than public spheres.

A lovely anecdote from my reading perfectly captures the era’s spirit: Since going out always carried some risk of surveillance or political scrutiny, people increasingly invited friends and family into their homes, where they could speak more freely within trusted circles. Dancing was a favorite pastime, but since one mustn’t be seen enjoying oneself too enthusiastically (propriety remained paramount), ladies wore little purses attached to their wrists containing needlework or lace patterns. Between waltzes, they would resume their virtuous handicrafts, maintaining the appearance of productive domesticity even while indulging in pleasure. It’s a perfect emblem of the era: genuine enjoyment constrained and disguised by the appearance of proper middle-class virtue.

With this understanding fresh in mind, I went to visit the greatest concentration of Biedermeier culture in Vienna: the MAK, or Museum of Applied Arts (Museum für angewandte Kunst). Founded by Emperor Franz Joseph in 1863, directly inspired by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (opened just ten years earlier), this stands as one of Europe’s most beautiful museums of decorative arts. With collections ranging from the Middle Ages through contemporary design, it offers something to captivate every visitor.

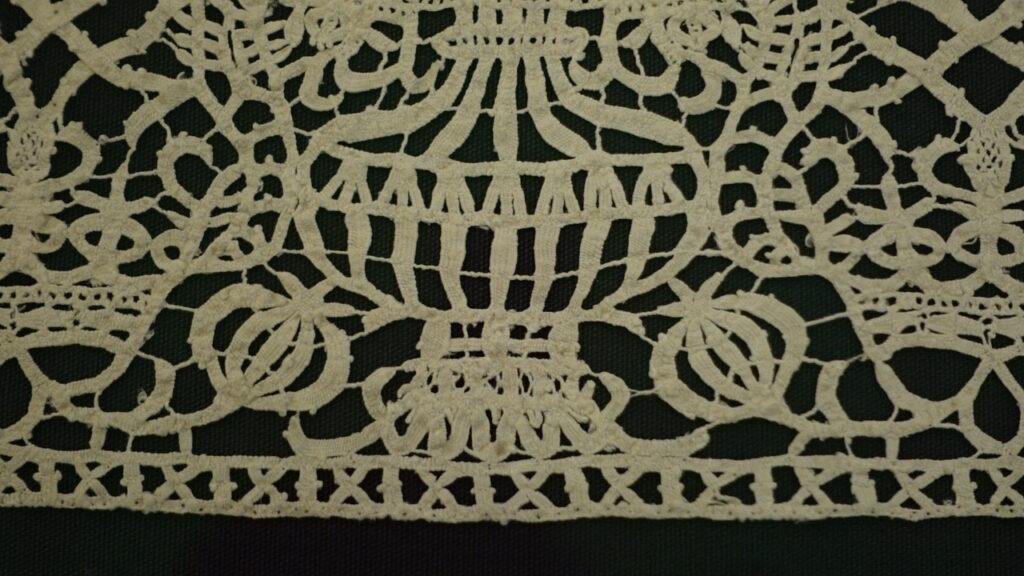

As soon as I entered, I plotted the fastest route to the Biedermeier galleries—but the universe had other plans. With that lace anecdote still fresh in my mind, I entered the glassware gallery only to discover an extensive collection of Austrian lace covering the entire gallery walls. It was extraordinary timing, almost uncanny—a mesmerizing voyage through patterns and artistry, intricate work that represented countless hours of feminine labor, skill passed from generation to generation, beauty created in those very domestic spaces the Biedermeier era so celebrated.

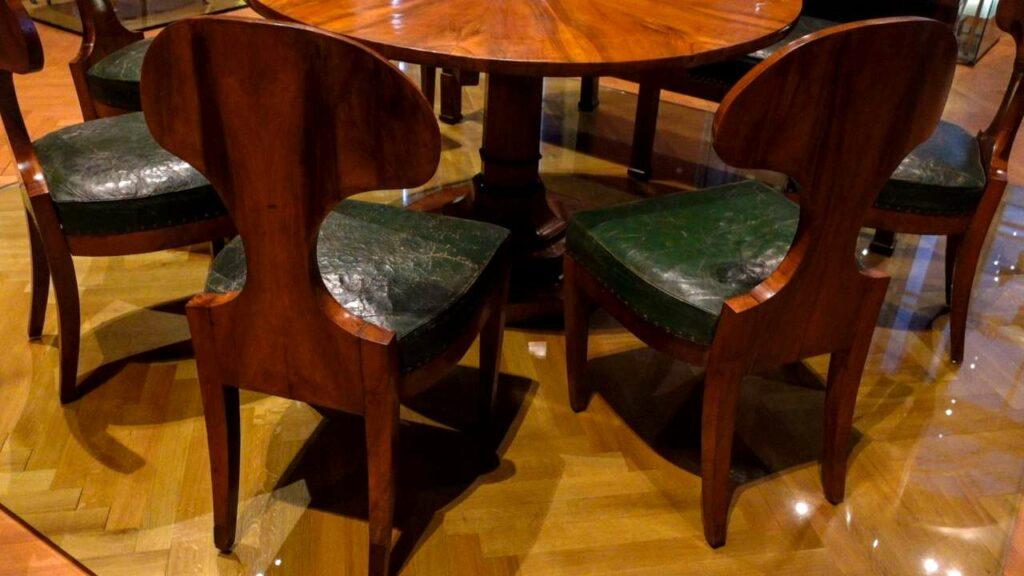

The Biedermeier gallery itself occupies one of the museum’s most beautiful salons. The furniture immediately reveals designs oriented toward craftsmanship and comfort rather than ostentatious display. Biedermeier pieces gather inspiration from French Empire style but express it in simplified, more accessible forms—elegant without being intimidating, refined without requiring vast wealth. This represents the first decorative style in European history that emanated from the middle class rather than aristocracy, designed for homes of moderate size and budgets rather than palaces.

In my view, this offers a significant example of how aristocratic culture can uplift all social classes by making them aspire to beauty within their own environments rather than simply negating or forbidding everything associated with higher ranks. The Biedermeier says: you too can have beautiful things, can create aesthetic pleasure in your daily life, can cultivate taste and refinement regardless of your birth. It’s a democratic vision of beauty.

The chair timeline display proved absolutely fascinating—watching the evolution of form and function across decades, seeing how a single object type can express shifting values and aesthetics. And the porcelain… well, you can imagine how I felt. Case after case of exquisitely painted pieces, delicate forms that transform functional objects into small works of art. This was porcelain designed not for state banquets but for family dinners, for afternoon coffee with neighbors, for the intimate scale of middle-class domestic life.

The Biedermeier era wasn’t perfect—political repression shaped its inward focus, and we shouldn’t romanticize authoritarian constraint. Yet something valuable emerged from those limitations: a profound appreciation for domestic beauty, for the pleasures of home and family and private creativity. The understanding that a well-designed chair, a lovely teacup, an evening of music with friends in your own parlor—these simple things constitute not mere comfort but a kind of spiritual nourishment.

So for this solstice evening, I invite you to fully embrace your cozy interior, whatever form it takes. Brew tea in your most beloved cup. Light candles that please you. Arrange objects that bring beauty to your sight. Whether entertaining cherished friends or simply enjoying your own company, take time to savor the peace of the longest night. The Biedermeier understood something essential: when the outside world feels uncertain or unwelcoming, cultivating beauty and comfort at home becomes not escape but sustenance, not frivolity but necessary care for the soul.

Tomorrow the light begins its return, imperceptible but certain. Tonight, we rest in the dark, at home, surrounded by whatever beauty we’ve chosen to create around ourselves.

Until tomorrow, dear friends—happy reading, happy solstice, and may your domestic kingdom be everything your heart needs it to be.

THE BIEDERMEIER ERA (1815-1848):

Historical Context:

- Period: Between Congress of Vienna (1815) and Revolutions of 1848

- Geography: Primarily Austrian Empire, also German states

- Political climate: Conservative restoration under Chancellor Metternich

- Censorship: Heavy restrictions on political speech, press, assembly

- Social shift: Rise of prosperous middle class (Bürgertum)

- Cultural response: Turn inward toward domestic life, private pleasures

The Name: “Biedermeier” derives from a fictional character—Gottlieb Biedermaier, a simple, conventional petit bourgeois created by poets as gentle satire of middle-class values. The name was later applied to the entire era, initially with mocking connotations but eventually as neutral historical descriptor.

Characteristics:

In Design & Furniture:

- Simple, functional forms

- Quality craftsmanship over ostentation

- Light-colored woods (cherry, birch, maple, pear)

- Clean lines, gentle curves

- Comfortable seating

- Human scale (designed for actual homes, not palaces)

- Inspired by French Empire but simplified

- First truly middle-class decorative style

In the Visual Arts:

- Intimate domestic scenes

- Portraits of middle-class families

- Landscapes and nature

- Genre painting (everyday life)

- Attention to detail and realism

- Artists: Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, Friedrich Gauermann, others

In Music:

- Franz Schubert’s Lieder and chamber music

- Home musicales (Hausmusik)

- Piano as center of domestic entertainment

- Songs suitable for amateur performance

- Dance music—waltzes especially

In Literature:

- Focus on private life rather than grand historical themes

- Adalbert Stifter’s detailed nature descriptions

- Eduard Mörike’s poetry

- Franz Grillparzer’s dramas

In Social Life:

- Home entertaining over public gatherings

- Kaffeeklatsch (coffee gatherings)

- Needlework and handicrafts

- Amateur theatricals

- Reading circles

- Dancing parties in private homes

MAK MUSEUM (Museum für angewandte Kunst):

About the Museum:

- Founded: 1863 by Emperor Franz Joseph

- Inspiration: Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1852)

- Original name: k.k. Österreichisches Museum für Kunst und Industrie (Imperial Royal Austrian Museum for Art and Industry)

- Current location: Stubenring 5, Vienna

- Architecture: Heinrich von Ferstel (Renaissance Revival style)

- Mission: Bridge gap between art and industry, promote good design

Collections:

Historical Periods:

- Medieval

- Renaissance and Baroque

- Biedermeier (exceptional collection)

- Historicism

- Jugendstil (Art Nouveau)

- Art Deco

- Contemporary design

Why It Matters: The MAK’s Biedermeier collection is among the world’s finest, preserved with exceptional care and displayed to show not just individual objects but entire lifestyle systems—how rooms were arranged, how families lived, how beauty was integrated into daily middle-class life.

Visiting Information:

MAK Museum:

- Address: Stubenring 5, 1010 Vienna

- Hours: Tuesday 10am-9pm, Wednesday-Sunday 10am-6pm, closed Monday

- Admission: Moderate fee, reduced rates available, free on Tuesday evenings

- Special exhibitions: Regularly changing contemporary design shows

- Café: Beautiful MAK Café designed by Joseph Hoffmann

- Shop: Excellent selection of design books and objects

Tips:

- Allow at least 2-3 hours

- Biedermeier galleries are essential but don’t miss contemporary design areas

- Photography usually permitted without flash

- Less crowded than major art museums—peaceful experience

- Museum building itself is beautiful example of 19th-century architecture

BIEDERMEIER VALUES FOR MODERN LIFE:

The Biedermeier offers surprisingly relevant lessons for contemporary living:

Quality Over Quantity: Well-made objects designed for real use, not display or status

Domestic Beauty: Every room, every object can be beautiful—aesthetics aren’t reserved for public spaces

Home as Sanctuary: When external world feels chaotic, cultivate peace and beauty at home

Amateur Creativity: Music, art, handicrafts practiced for personal pleasure, not professional achievement

Intimate Gatherings: Small groups of trusted friends over large impersonal events

Comfort Without Guilt: Coziness (Gemütlichkeit) as positive value, not lazy indulgence

SOLSTICE BIEDERMEIER STYLE:

Create Your Own Biedermeier Evening:

- Set a beautiful table, even if dining alone

- Use your best porcelain and linens

- Light candles—Biedermeier loved soft lighting

- Play period music (Schubert especially appropriate)

- Read poetry aloud or to yourself

- Work on handicraft project

- Write letters to friends

- Arrange flowers or greenery thoughtfully

- Make hot chocolate or tea ceremony

- Appreciate your domestic space

The longest night invites us inward, and the Biedermeier understood that inward-turning need not mean deprivation but can mean cultivation of private beauty and peace.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.