There’s a particular kind of courage required to sit alone in a Parisian café with a book and a coffee, to claim a table meant for two and spread out your solitude like it’s something to be celebrated rather than apologized for. The first few times, you feel the weight of being watched—or worse, the imagined pity of passersby who assume you’ve been stood up, that your aloneness is a failure rather than a choice.

But here’s what Paris teaches you, slowly, persistently, through grey November afternoons and golden summer evenings: solitude is not the same as loneliness. Being alone is not a problem to be solved but a state to be cultivated, protected, even treasured.

Alexandra David-Néel understood this instinctively. In the opening pages of My Journey to Lhasa, she writes about her childhood self:

“Ever since I was five years old, a tiny precocious child of Paris, I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept. I craved to go beyond the garden gate, to follow the road that passed it by, and to set out for the Unknown. But, strangely enough, this Unknown fancied by my baby mind always turned out to be a solitary spot where I could sit alone, with no one near.“

Even as a child in Paris, before Tibet, before Buddhism, before becoming the woman who would disguise herself as a beggar to reach forbidden Lhasa, she was already seeking solitude. Not escape from people, exactly, but escape to herself—to that quiet center where observation becomes possible, where the mind can wander without interruption.

This November, as the city wraps itself in cashmere and early darkness, I want to talk about what it means to be a woman alone in Paris. Not tragically alone, not pitiably alone, but deliberately, deliciously alone—claiming space in a city that has always belonged as much to solitary wanderers as to lovers and crowds.

The Literary Tradition of Feminine Solitude

French literature has always understood something essential about solitude—that it’s not absence but presence, not emptiness but fullness. Listen to how Marguerite Duras describes it in Writing:

“La solitude, ce n’est pas être seul, c’est aimer d’être seul. C’est d’être seul aimé par quelqu’un qui ne sait pas qu’il vous aime en vous laissant seul.”

Solitude isn’t being alone, it’s loving being alone. It’s being alone loved by someone who doesn’t know they love you by leaving you alone.

There’s something almost mystical in that formulation—the idea that true solitude requires not just physical aloneness but a kind of blessing, a permission granted (even unknowingly) by others to claim that space for yourself.

Colette, who knew Paris intimately through multiple marriages, scandals, and transformations, wrote in The Vagabond:

“Ma solitude ne dépend pas de la présence ou de l’absence de gens; au contraire, je déteste qui me vole ma solitude sans, en échange, m’offrir une vraie compagnie.”

My solitude doesn’t depend on the presence or absence of people; on the contrary, I hate anyone who steals my solitude without, in exchange, offering me genuine companionship.

This is the distinction that matters: being alone by choice versus being alone by circumstance. The woman alone in Paris by her own design is engaged in something radical—she’s claiming time and space that society has historically told women should be filled with service to others, with relationships, with the endless work of being available.

Simone de Beauvoir understood this too. In The Second Sex, she writes about how women have been denied the luxury of solitude, how even their rooms (when they had rooms of their own) were subject to interruption, to the demands of domestic life. To be alone, truly alone, was to claim a kind of freedom that women weren’t supposed to want.

And yet, they did want it. They do want it. We want it still.

Annie Ernaux, in her stark, unflinching way, captures this in A Woman’s Story:

“J’ai toujours aimé être seule. Pas tout le temps, mais régulièrement. Comme si la solitude était une sorte de rendez-vous avec soi-même, un moment où l’on retrouve qui on est vraiment.”

I’ve always loved being alone. Not all the time, but regularly. As if solitude were a kind of appointment with oneself, a moment when you rediscover who you really are.

An appointment with oneself. What a perfect way to frame it—not as something that happens to you but as something you schedule, plan for, protect. A deliberate meeting with the person you are when no one else is watching.

The Flâneuse: Reclaiming the Streets

The flâneur—that iconic figure of 19th-century Paris, the gentleman stroller who wandered the boulevards observing modern life—was always coded male. Baudelaire’s painter of modern life, Walter Benjamin’s chronicler of the arcades, these were men who could wander freely, who could claim the streets as their salon, their studio, their stage.

But what about the flâneuse? The woman walker?

She existed, of course, though history has been slower to recognize her. She moved differently through the city, aware always of being watched as well as watching. Her solitude was more precarious, more open to interpretation and interruption. A man alone is a philosopher; a woman alone is assumed to be waiting for someone.

Virginia Woolf, during her visits to Paris, wrote in her diary about the particular pleasure of walking alone through unfamiliar streets:

“I like to walk about London and Paris alone, in the evening, looking in at windows and watching people.”

There’s something both vulnerable and powerful in that simple declaration. The woman alone, looking in at windows—both observer and observed, both inside and outside the life of the city.

Today, being a woman alone in Paris still carries echoes of that complicated history. But it also carries possibility. Every time we sit alone in a café without apologizing, every time we go to a museum or a restaurant or a cinema by ourselves, we’re quietly insisting: this space is mine too. I don’t need a companion to legitimize my presence here.

Three Sacred Spaces: My Parisian Rituals of Solitude

Paris has given me many places where my solitude feels not just permitted but celebrated, where being alone amplifies rather than diminishes the experience. These are my ritual spaces, the destinations I seek when I need to remember who I am beneath all the roles I play. Here are just three of them :

1. The Carnavalet Museum: Time Travel Through Parisian Salons

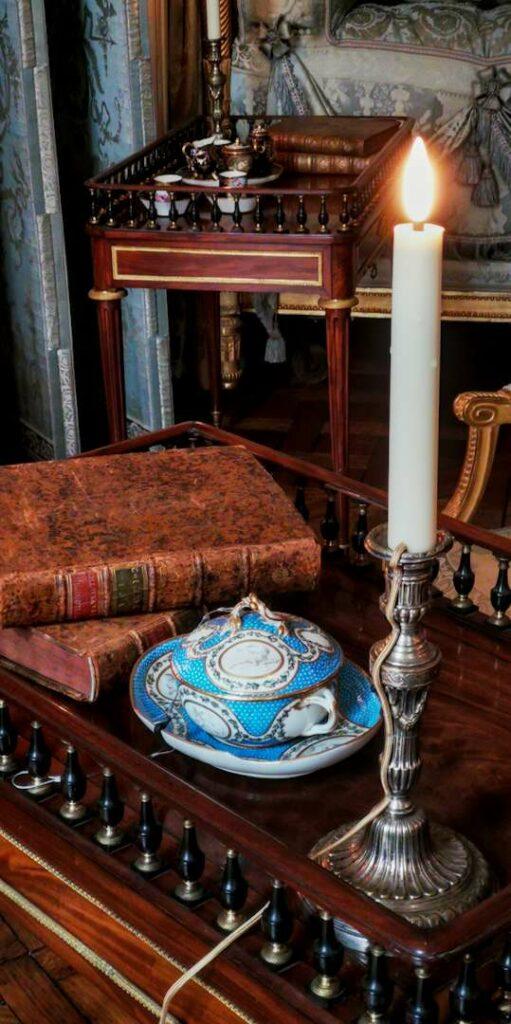

The Musée Carnavalet sits quietly in the Marais, holding within its walls the entire history of Paris. Since its recent renovation, the museum has become something even more magical—a portal not just to Paris’s past but to a particular feeling of pastness, a carefully curated dreamscape of what it might have been like to live in those other centuries.

I go there alone, deliberately, because this is a solitude that requires no hurrying. The permanent collection is free, and perhaps because of this—or perhaps because tourists are drawn to the Louvre and Orsay—it’s rarely crowded. You can wander the period rooms without jostling for position, without the constant awareness of others waiting their turn.

These rooms! They’ve recreated entire salons, transplanted the paneled walls and painted ceilings and gilded furniture from demolished hôtels particuliers. You step through a doorway and suddenly you’re in a late 18th-century drawing room, or a Belle Époque jeweler’s shop, or Proust’s bedroom with its actual cork-lined walls.

What I love most is the feeling of being invited in. Not as a tourist behind velvet ropes but as a guest, as if these beautiful Parisian salons of centuries past are opening their doors specifically for me. I imagine the women who once inhabited these spaces—the salon hostesses like Madame Geoffrin or Madame du Deffand, who wielded influence through conversation and wit when they were denied formal power.

The museum is a place where solitude enhances observation. Alone, I can stand in front of a tiny painted fan or an elaborate writing desk for as long as I want. I can read every placard, absorb every detail, let my imagination reconstruct the lives that touched these objects. I can sit on the benches and simply be in these transported rooms, feeling the weight of history settle around me like a cashmere shawl.

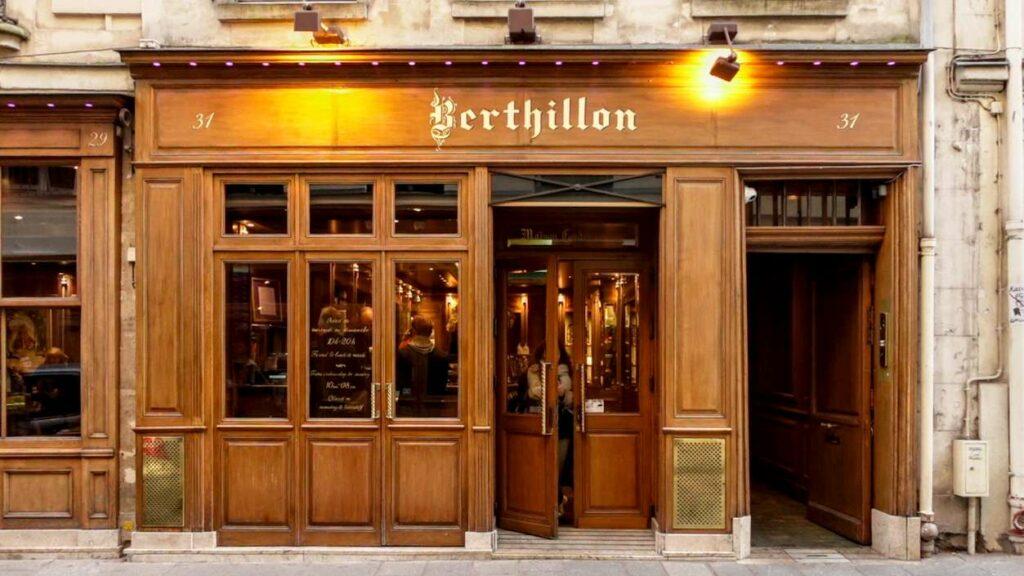

2. Berthillon: The Democracy of Ice Cream

If the Carnavalet is about the past, Berthillon is emphatically about the present—the living, breathing, sweetly indulgent present of Parisians doing what they do best: taking their pleasure seriously.

Everyone knows about Berthillon ice cream. It’s famous, legendary even, the glacerie on Île Saint-Louis that’s been making artisanal ice cream since 1954. What most tourists don’t know—or don’t bother to discover—is that there’s a world of difference between grabbing a cone to go and sitting inside the parlour itself.

I go there alone specifically so I can do what tourists rushing to the next monument cannot: I sit inside and listen.

Inside Berthillon, time moves differently. Old ladies settle into chairs and order elaborate coupes with the gravitas of sommeliers choosing wine. They chat about common acquaintances, about whose granddaughter just got married, about how the weather has been terrible this year—vraiment terrible. Solo readers claim corner tables and order combinations that sound completely mad—lavender with salted caramel, bergamot with dark chocolate—and proceed to savor them with the kind of focused attention usually reserved for meditation.

The conversations I hear! Fragments of Parisian life that you could never script:

“Non mais elle a vraiment osé lui dire ça? En plein restaurant?“

“The fig and honey is divine this year, absolutely divine.“

“Tu te rends compte qu’on se connaît depuis cinquante-trois ans?“

This is the Paris I came here for—not the Paris of tourist traps and luxury shopping, but the Paris of people living their ordinary, extraordinary lives, taking time in the middle of a Wednesday afternoon to eat ice cream and talk about everything and nothing.

Being alone at Berthillon is a particular kind of anthropological pleasure. I’m not performing togetherness, not splitting my attention between a companion and my observations. I can simply absorb the atmosphere like it’s another flavor—the sound of the voices, the scrape of spoons against stainless steel dishes, the way light filters through the windows onto marble-topped tables.

Marguerite Duras wrote about sitting alone in cafés:

“Je suis seule. Mais je ne suis pas seule. Il y a les autres, tout autour, qui vivent leurs vies, et je vis la mienne en même temps. C’est une solitude peuplée, et c’est exactement ce dont j’ai besoin.”

I am alone. But I’m not alone. There are others, all around, living their lives, and I’m living mine at the same time. It’s a populated solitude, and it’s exactly what I need.

That’s Berthillon. That’s why I go there by myself, with a book I may or may not read, to order my own mad combination of flavors (currently: blackcurrant and pistachio, if you must know) and to sit in that particular state of being alone together with strangers.

3. Roland Garros: The Collective Solitude of Sport

If someone had told me ten years ago that I’d find spiritual sustenance at a tennis tournament, I would have laughed. I’m not particularly athletic. I don’t play tennis. But Roland Garros has become one of my most beloved solitary rituals—precisely because of the paradox it represents.

I go alone so that I can fully feel the pulse of the courts, the waves of encouragement that wash over the stadium as champions battle without even touching each other. There’s something profoundly moving about the collective investment in individual excellence, about thousands of people rooting for someone they’ll never meet, feeling genuine joy at their victories and genuine grief at their defeats—all without any personal gain whatsoever.

This is the opposite of the Carnavalet’s quiet contemplation or Berthillon’s gentle people-watching. This is electric, ecstatic, communal. But I need to be alone to truly experience it.

When you go with someone, you’re always partly performing spectatorship—commenting on plays, explaining rules, sharing reactions. When you go alone, you can surrender completely to the experience. You can let yourself get swept up in the momentum shifts, the impossible comebacks, the heartbreaking defeats. You can cry when your player loses without worrying about seeming ridiculous. You can leap to your feet shouting “ALLEZ!” with complete abandon.

There’s a particular kind of camaraderie that happens at Roland Garros when you’re alone. The person next to you becomes, temporarily, your companion in enthusiasm. You don’t know them, you’ll never see them again, but for these hours, you’re united in caring deeply about the same thing. You exchange glances after an incredible point—”Did you see that?!”—without needing to speak. You groan together over a double fault. You hold your breath together during match point.

Going to Roland Garros alone is my reminder that solitude doesn’t mean separation. It’s possible to be fully present to your own experience while also being woven into the collective experience around you. It’s the joy of rooting for someone without any agenda, the pure pleasure of caring about something for no reason except that caring feels good.

And when I walk out of the stadium, still buzzing with adrenaline, still replaying that impossible backhand winner, I carry that feeling back into the city with me—the knowledge that Paris is full of these moments where solitude and communion aren’t opposites but two sides of the same coin.

What Solitude Teaches: The Courage to Disappoint

Here’s what being alone in Paris has taught me: solitude requires the courage to disappoint.

To disappoint the people who expected you to be available. To disappoint the cultural narrative that says women should be relational above all else, should derive their identity from their connections to others. To disappoint the part of yourself that was raised to believe that being alone meant being unwanted.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote:

“On ne naît pas femme : on le devient.”

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.

Part of that becoming, I think, is learning when to say no—to invitations, to expectations, to the assumption that your time belongs to anyone but yourself.

Being a woman alone in Paris—in a café, a museum, a stadium, on a bench in the Luxembourg Gardens—is a small revolution. It’s saying: I’m not waiting for anyone. I’m not lost. I’m not pitiable. I’m here because this is exactly where I want to be, in my own company, which is excellent company actually, thank you very much.

Annie Ernaux:

“La solitude est une sorte de liberté. Pas la liberté de faire ce qu’on veut—ça, c’est autre chose—mais la liberté d’être ce qu’on est, sans masque, sans performance.”

Solitude is a kind of freedom. Not the freedom to do what you want—that’s something else—but the freedom to be what you are, without mask, without performance.

Without performance. That’s the key. When you’re alone, you can stop performing. You can stop managing how you’re perceived, stop adjusting your reactions for an audience, stop being aware of yourself as a character in someone else’s story. You can simply be—reactive, contemplative, bored, delighted, melancholic, euphoric, whatever you actually are in that moment.

A November Ritual: The Appointment With Yourself

So here’s my invitation this November: Make an appointment with yourself in Paris, or in your own city, wherever you are.

Choose a destination—a museum, a café, a park, a cinema, an ice cream parlour, anywhere that calls to you—and go there alone. Not because you couldn’t find anyone to accompany you, but because you’re choosing your own company.

Notice how it feels. Notice the initial self-consciousness, if it’s there. Notice when it fades. Notice what you observe when you’re not dividing your attention. Notice how you inhabit space differently when you’re not performing companionship.

Bring a book if you want, or don’t. Bring a journal and write, or don’t. The only requirement is that you be intentionally, deliberately alone—that you treat this solitude not as a gap to be filled but as an experience in itself, worthy of your full attention.

Alexandra David-Néel wrote in her journals:

“Je n’ai jamais eu peur de la solitude. Au contraire, c’est dans la solitude que je me sens le plus vivante, le plus réelle, le plus moi-même.”

I was never afraid of solitude. On the contrary, it’s in solitude that I feel most alive, most real, most myself.

This is what Paris can teach you, if you let it: that being alone is not a problem to be solved but a state to be cultivated. That solitude is not the absence of connection but a different kind of connection—to yourself, to the city, to the quiet center where your truest self lives.

This November, give yourself the gift of that appointment. Meet yourself in a place that matters, and discover what happens when you show up fully present to your own company.

I promise you: it’s excellent company.

Until next time, enjoy your reading, and your solitude.

What are your sacred spaces for solitude? Where do you go to be deliberately, deliciously alone? I’d love to hear about the places that hold your solitude gently, that remind you who you are when no one else is watching.

Shop the Bookshelf

Here are the links to your stack of inspirational books by women who understood and cherished their solitude – may they guide you towards your own ritual of communion with the self.

A short note on how and why I share book links

Alexandra David-Néel : My Journey to Lhasa 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Marguerite Duras : Wartime Notebooks 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Colette : The Vagabond 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Simone de Beauvoir : The Second Sex 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Annie Ernaux : A Woman’s Story 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Virginia Woolf : Diary 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.