Beyond the Champagne Glass: Why Etiquette Still Matters in a Digital Age

The algorithm knew me too well. A few years ago, my Instagram feed served up a video of William Hanson—impeccably dressed, delightfully dry—explaining why you should never clink glasses during a toast if you’re drinking champagne. The delivery was pure British understatement: precise, gently mocking, utterly confident in its own absurdity. I watched three more videos. Then I joined the waiting list for his (then, upcoming) book.

What began as mild amusement at viral etiquette content spiraled into a deeper exploration of social grace. If a contemporary British expert could make manners feel relevant again, what had his predecessors—like Emily Post and Eleanor Roosevelt—said? What did Americans think about all this? And more pressingly: what do these rules—so specific, so laden with assumption—actually reveal about the cultural differences between the United States and the United Kingdom?

This is not an article about which fork to use or how to hold a teacup. This is my curious dive into the history of American etiquette and British courtesy. By looking at three distinct voices spanning a century, we can see how the “rules” of society act as a mirror to our shared history.

Emily Post and the Blueprint for American Social Order

I started, naturally, with the one I’d only ever known as a punchline in decades of American films: Emily Post.

Born Emily Price in 1872 to a prominent Baltimore family, Post lived a life that reads like a novel—a privileged childhood, a disastrous marriage that ended in divorce (scandalous for the era), a reinvention as a writer and arbiter of taste. Her most famous work, Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home, published in 1922, became an immediate bestseller and established her as America’s foremost authority on proper conduct. The book was my entry point into what she called “the Best Society”—her term for the community of well-mannered people, regardless of wealth or birth.

The Forensic Precision of “Best Society”

Post’s writing is extensive, meticulous and refreshingly unafraid. She explains rules with forensic precision, but she never shies away from pointing out the faults she observed so sharply in American society. She frequently puts American etiquette into perspective by comparing it to European customs, and she often contrasts East Coast and West Coast manners with what can only be described as elegant sarcasm.

The book feels like a long talk with an old aunt—the one who still wears her silk gloves to the opera and is never seen without her pearls, but who’s keen on having a little talk (perhaps even a touch of gossip) about the ways of the world.

Emily Post was often described by her contemporaries as somewhat spoiled, a product of privilege. But she allows herself the liberty—perhaps stemming from that very privilege—of saying things that are completely avoided in today’s world. A shame, really, since this would be such a useful reminder in the age of social media:

Nearly all the faults or mistakes in conversation are caused by not thinking. For instance, a first rule for behaviour in company is “Try to do and say only that which will be agreeable to others”. Yet how many people who really know better, people who would be perfectly capable of intelligent understanding if they didn’t let their brains remain asleep or locked tight, go night after night to dinner parties, day after day to other social gatherings, and absent-mindedly chatter about this or that without ever taking the trouble to think what they are saying and to whom they are saying it.

Emily Post

The Linguistic Mirror: How Our Words Reveal Our Culture

For a reader and passionate linguist like myself, Post offers a rare delight—a rule that used to be the basis of any education, and that seems to have become more and more invisible today:

It is rather curious that we Americans, who care so very much about the idea of “Culture” in the abstract, are often unaware that the measure of our own cultivation is made evident the moment we speak. Nothing so instantly, and so irrefutably, reveals the social quality of our background—our advantages or our disadvantages—as the words we choose and the way we pronounce them.

Emily Post

And then, the prescription that would revolutionize modern discourse if anyone still followed it:

There is no better way to cultivate taste in words than by constantly reading books of proved literary standing. But it must not be forgotten that there can be a vast difference between literary standing and popularity, and that many of the “best-sellers” have no literary merit whatsoever.

Emily Post

Post’s etiquette is architecture—external, structural, concerned with how we appear in the intricate dance of social interaction. She assumes the inner life; she focuses on its expression. Courtesy, in her vision, is about creating comfort for others through predictable, thoughtful behavior.

Eleanor Roosevelt: Transforming Etiquette into a Philosophy of the Self

Forty years later, another American woman took up the question of manners. But Eleanor Roosevelt’s life—and her book—could not have been more different.

Defined in many ways by her husband’s political career, Roosevelt nonetheless carved out a legacy entirely her own. She gave speeches that shaped public opinion, championed civil rights and reimagined what it meant to be a public woman. Her Book of Common Sense Etiquette, published in 1962, emerged from this context—a world transformed by war, economic upheaval and profound social change.

From Social Performance to Character Formation

Where Post says “this is how you should appear to others,” Roosevelt says “this is how you should envision your life”—a giant step toward the modern way of building a society. Not well-behaved individuals keeping up appearances for the sake of social order, but balanced, fulfilled individuals coming together because they’ve done the inner work.

The difference is immediately apparent in Roosevelt’s prose:

The one who is neat and orderly in his own affairs, indulges in harmless pleasures that give him satisfaction, takes reasonable and intelligent care of his health, rests when fatigued, refuses to become angry at himself when he has done a stupid thing, arranges his life efficiently so that he minimizes wasted time and effort, can amuse himself in leisure hours when he is alone, learns how to be honest to others by being honest with himself, not only will find the basic rules of courtesy to others natural and simple, but will also render perhaps the greatest of all courtesies to those with whom he has daily contact—that of being the kind of human being with whom it is a privilege to associate.

Eleanor Roosevelt

This is etiquette as character formation. Roosevelt begins from the inner life—self-confidence, conscience, courage—and then draws conclusions about how to act toward others. Post begins from social interaction—comfort, consideration, graceful behavior—and leaves the inner work largely implied rather than explored.

A World in Transition: Manners After the Great Wars

Roosevelt’s book includes extensive chapters on family dynamics: the relationship between husband and wife, and a somewhat dated section on “The Good Wife” (though to be fair, she does attempt to address men’s duties in “The Courteous Husband”—the balance between the two still reads like a story from an era when married women were primarily homemakers). There’s a chapter on children’s education, and most interestingly, on the role of grandparents, who should not interfere with either the household or the upbringing of grandchildren.

She even includes a reminiscence of household staff management—echoes of our Downton Abbey rules, complete with proper wardrobe—but with the added modernity of acknowledging that servants were becoming less and less common, both economically and practically.

It’s remarkable how these two women were contemporaries, yet their books, written forty years apart, perfectly mirror the changes society underwent during and after World War II. Post wrote just four years after the end of World War I, in an age that could not yet conceive of such radical shifts—an era not yet ready for books on how husbands and wives should conduct themselves in the privacy of their homes. When Roosevelt put pen to paper, the world had transformed entirely. The war had given women radically different roles in society. The balance had shifted, profoundly and irrevocably.

William Hanson: Reclaiming Courtesy with British Wit

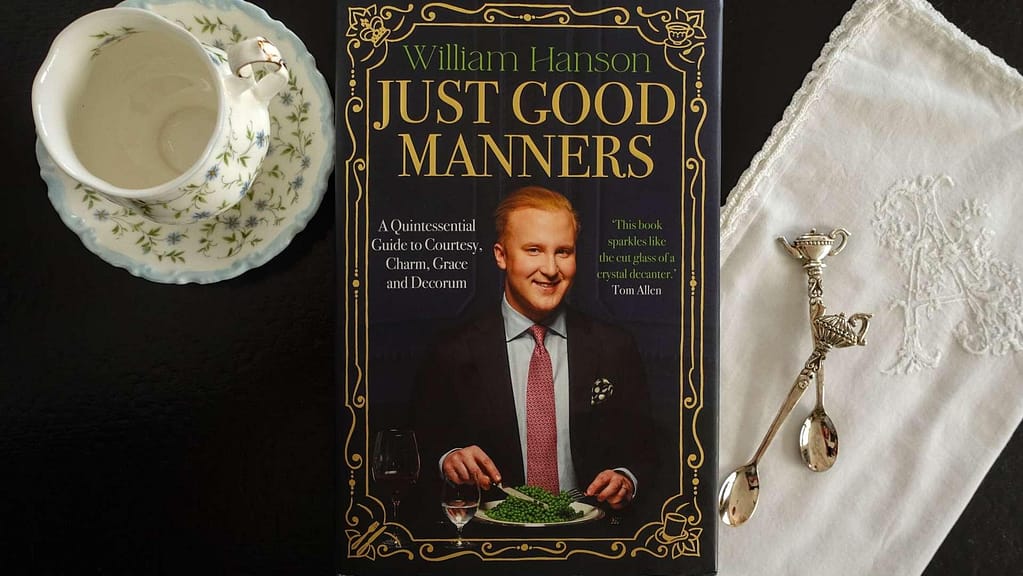

And speaking of radical shifts—my choice for an overview of English etiquette is rooted in our own era, with the excellently written guide by etiquette expert William Hanson, Just Good Manners.

William Hanson is Britain’s leading etiquette coach, advising everyone from international businesses to the perennially bewildered on how to navigate social situations with grace. His 2024 book, Just Good Manners: A Quintessential Guide to Courtesy, Charm, Grace and Decorum, is both a comprehensive manual and a witty commentary on contemporary life. What drew me to Hanson in the first place—that Instagram presence, that perfectly calibrated blend of authority and humor—translates beautifully to the page.

The Digital Shift: From Table Grace to Instagram Etiquette

This overview of courtesy and grace touches on many themes found in every etiquette guidebook on the planet: greetings, table manners, polite conversation. What distinguishes Hanson’s approach is the dose of humor that accompanies the form:

Many years ago in Britain, people would say a small prayer, called a “grace”, before they ate the food. Now they take photographs. The custom may be different but, if I am being charitable, capturing your meal on your camera roll is the new way to acknowledge and be grateful for what you are about to eat. Formally, of course, it is not correct.

William Hanson

His writing is a uniquely British blend of polished language and relaxed approach—the kind of assurance that comes from being perfectly in tune with your message while accepting that, despite your best intentions, it might not be received as you’d hoped. But that is never an excuse to abandon your beliefs.

Toxic or Timeless? Stripping the Elitism from Modern Manners

Hanson understands something crucial about our contemporary moment: the word “etiquette” has become almost toxic, associated with elitism, exclusion and gatekeeping. His project is to reclaim it:

“Etiquette” has become a loaded word. Its grander French etymology adds some off-putting gilding. It may be hard for someone who has had a far-from-royal upbringing to think they need to observe the rules of etiquette. But every situation involves a code of behavior, whether people like it or not. It’s not just about who is presented to whom at court; it’s how to handle breakups with grace and to let a restaurant know you are still coming the day before. I dare say there is even etiquette around a gangland drug exchange! So long as humans interact with one another, there will be the need for etiquette and manners.

William Hanson

This is the completion of a century-long arc. Post built the architecture. Roosevelt insisted on the foundation. Hanson says: the structure still matters, but only if we remember why we’re building it in the first place—not to exclude, but to include. Not to perform superiority, but to create comfort. Not to enforce hierarchy, but to acknowledge that we share space, and sharing space requires intention.

The Global Language of Courtesy: What Two Nations Tell Us About Humanity

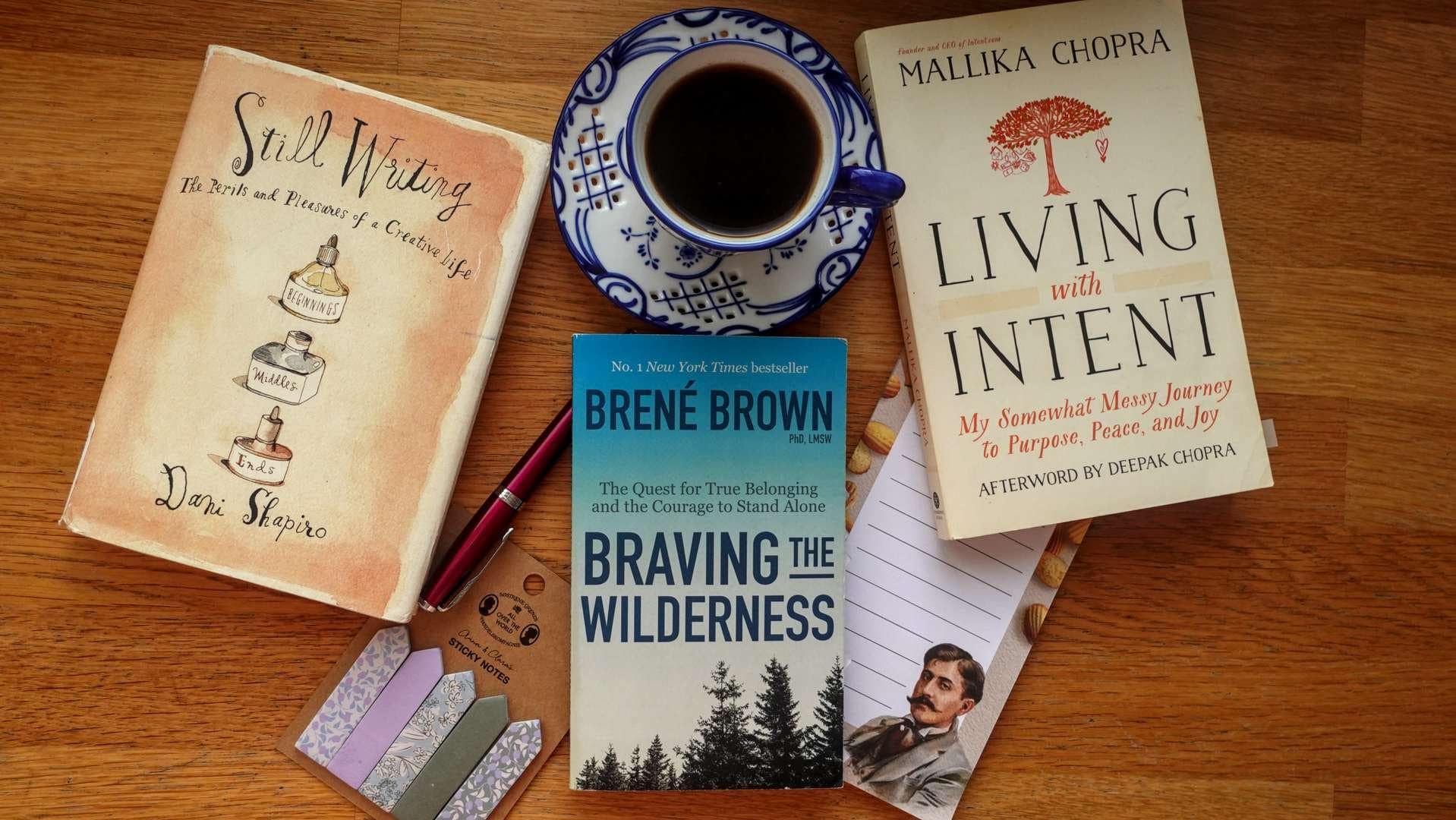

These three books—separated by geography, generation and circumstance—sketch the outline of Anglo-American etiquette across a transformative century. From Post’s precise blueprints for Best Society to Roosevelt’s psychology of courtesy to Hanson’s contemporary reclamation, the evolution is unmistakable.

What emerges is not a single vision of manners, but a conversation about what it means to live among others when the rules keep changing. Post assumed a stable social order and wrote the manual for navigating it. Roosevelt witnessed that order collapse and rebuilt etiquette from the inside out. Hanson inherits a world where the very concept of shared standards feels suspect, and makes the case for keeping them anyway—not as instruments of exclusion, but as tools for collective flourishing.

The United States and the United Kingdom share a language, part of their history and a certain pragmatic approach to courtesy. But even within this shared tradition, the emphasis shifts. American etiquette, at least in Post’s formulation, tends toward explicit instruction, detailed scenarios and comprehensive coverage. Roosevelt’s American vision is deeply psychological, focused on self-cultivation as the prerequisite for social grace. British etiquette, as Hanson presents it, carries a lighter touch—humor as lubricant, understatement as style, the assumption that you’ll figure out the nuances if the principles are sound.

These are not just different books about the same subject. They are different philosophies about what courtesy is for, and what kind of society it serves.

The Journey Continues: Next Stop, France

In the next installment of this series, I’ll be crossing the Channel to explore French etiquette—a tradition that influenced Post, shaped Roosevelt’s thinking, and provides an elegant counterpoint to the Anglo-American approach. Because if there’s one thing I’ve learned from this deep dive into manners across cultures, it’s that what we share as common sense reveals as much as what distinguishes us.

The French have their own vision of courtesy, their own priorities and their own blind spots. And understanding those differences illuminates not just French culture, but our own assumptions about what it means to be polite, considerate and civilized.

Until then, I’ll be practicing my champagne toasts—without clinking, naturally.

What’s your relationship with etiquette guides? Have you encountered Emily Post, Eleanor Roosevelt, or William Hanson in your own reading? And more importantly: do you believe manners still matter in our modern world, or have we outgrown the need for such formal frameworks?

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below, or feel free to share your own cultural etiquette traditions—the unwritten rules that shaped how you learned to move through the world.

Note: This is Part II in my series “The Art of Living Among Others,” exploring etiquette and good manners guides through several cultures and languages.

Read Part I: In Defense of Good Manners to discover why etiquette might be the secret to modern freedom.

The Reading List

For the Traditionalist: Etiquette in Society, in Business, in Politics, and at Home by Emily Post – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Modern Soul: Book of Common Sense Etiquette by Eleanor Roosevelt – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Contemporary Skeptic: Just Good Manners by William Hanson – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.