February Literary Mood Board • The Art of Good Manners, Part I

February arrives with its own particular atmosphere — the deep quiet after the holidays have ended, the liminal space between abandoned resolutions and the distant promise of spring. It is a month that invites reflection rather than momentum, inward adjustment rather than reinvention. This year, it has drawn me toward something that feels both antiquated and unexpectedly urgent: the art of good manners in a digital age.

These past few weeks, I’ve been unusually out and about. More lunches with friends than I’m accustomed to. Museum exhibitions that required advance booking and early morning alarms. A quick forty-eight hours abroad that involved two airports, two buses, security queues and one particularly loud group of people (I won’t mention their origin, it would be a shame to generalise their lack of civility to a whole country).

There is nothing quite like time spent in transit — in airports, on public transport, in crowded cafés — to sharpen one’s awareness of how we share space. Or fail to. Whether it’s a phone call conducted at full volume in a quiet carriage, or a waiter addressed as if they were part of the furniture, these moments make something quietly obvious: we seem to have lost a shared language for moving through the world with consideration.

Redefining Modern Etiquette as Freedom

I may be old school. Some might call this perspective conformist, or worse, conservative. But I’ve come to believe that good manners are not a constraint on freedom — they are one of its conditions. More than that, etiquette is a form of respect not only toward others, but toward ourselves. It feels almost quaint to speak of respect in an age of speakerphone conversations on buses, of headlights flashed aggressively so the car ahead will move aside, shaving seconds off a commute at the expense of safety if not collective calm. And yet, perhaps this is precisely why the question feels so pressing.

This month’s literary mood board is dedicated to the lost art of courtesy — not the stiff, exclusionary kind that exists to maintain class barriers, but the kind that recognises a simple truth: we live together. And in this common space, consideration is not weakness, restraint is not submission. A functioning society depends on small, often invisible acts of care.

This is the first article in a series exploring good manners guidebooks from six different cultural traditions — the UK, France, the USA, Spain, Italy and Romania. Not because these cultures hold a monopoly on courtesy, but because they are the languages I speak and the traditions I know well enough to explore with nuance rather than assumption. Reading etiquette texts in their original languages has allowed me to notice both the shared values that unite them and the subtle differences that reflect distinct moral priorities — details that are often flattened in translation.

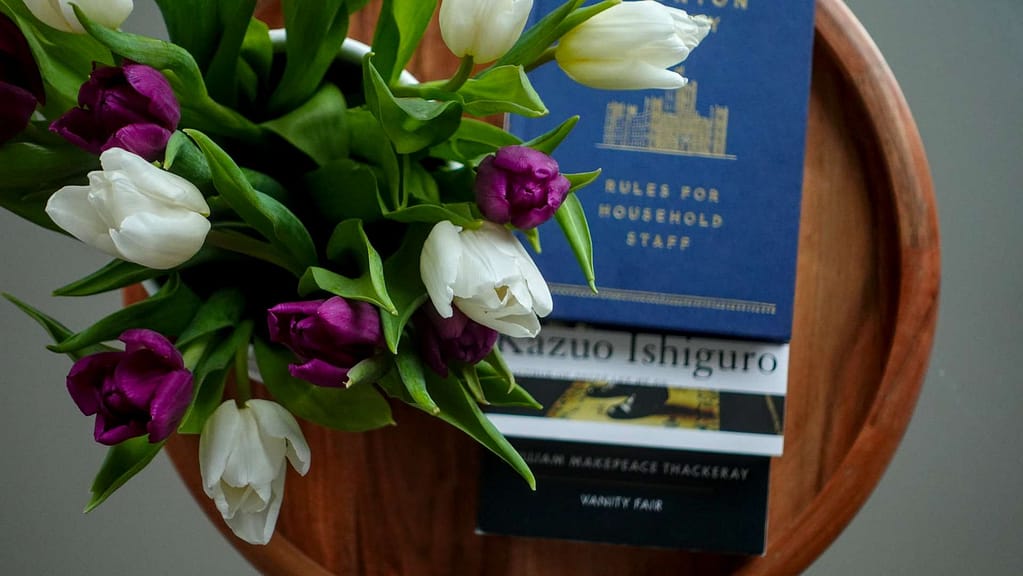

The Etiquette Reading List: Four Books on Character and Conduct

For this opening chapter, however, I’ve chosen four books that don’t quite fit the geographical structure but felt essential for laying the groundwork. Two are guides to conduct; two are novels that interrogate what happens when rules are followed too rigidly, or learned too superficially. Together, they trace the outline of what a modern etiquette might look like: rooted in respect, attentive to character and flexible enough to serve rather than suffocate.

Etiquette in Literature: Lessons from Downton Abbey and Kazuo Ishiguro

When I began thinking about manners through literature rather than manuals, I realised how often stories have shaped my understanding of dignity more deeply than any list of rules. Not through instruction, but through character — through observing how people carry themselves, how they inhabit their roles, how they treat others when no one is watching.

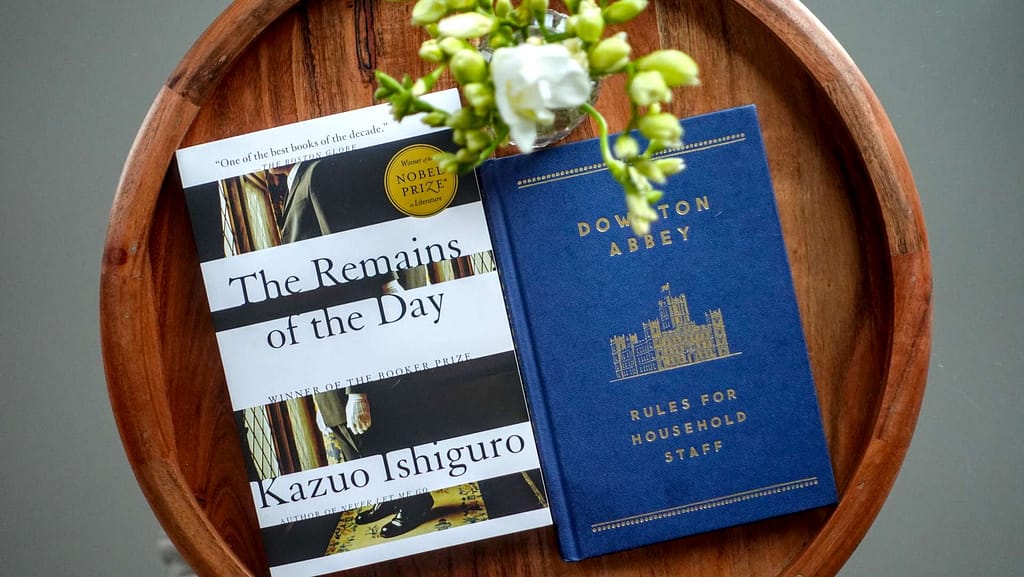

This is why The Downton Abbey Rules for Household Staff, written in the unmistakable voice of Mr. Carson, surprised me. I approached it expecting novelty: a charming relic of Edwardian obsessiveness, something to skim while congratulating myself on modern enlightenment. What I found instead was a vision of etiquette as dignity — complicated, historically burdened, but not without moral substance.

The rules Carson outlines are meticulous, even severe. And yes, the class system that produced them was an imperfect one. But these rules were not designed to humiliate those who followed them. In their own limited and questionable way, they offered protection. A butler who mastered his conduct, who understood the choreography of service, possessed a form of dignity that transcended his station. Not because he served the powerful, but because he served with excellence.

This idea finds its most searching fictional exploration in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Stevens, the novel’s narrator, has devoted his entire existence to the ideal of perfect service. His restraint, his discipline, his devotion to professionalism are not treated as ridiculous — they are treated as serious, even noble. The tragedy of the novel is not that Stevens believed in dignity through conduct, but that the world he lived in demanded the silencing of his inner life in order to achieve it.

Etiquette is not the villain here. Rigidity is. Stevens mistakes the performance of dignity for dignity itself, and pays a devastating price. Yet Ishiguro never mocks his devotion. Instead, he forces us to ask where conduct ends and self-negation begins.

Read together, these two books suggest something quietly radical: respect is not a question of class, but it is a question of conduct. Mastery, attentiveness, and care confer dignity regardless of social status. Etiquette elevates when it is practiced as a form of responsibility — and diminishes when it becomes a gatekeeping mechanism rather than a shared skill.

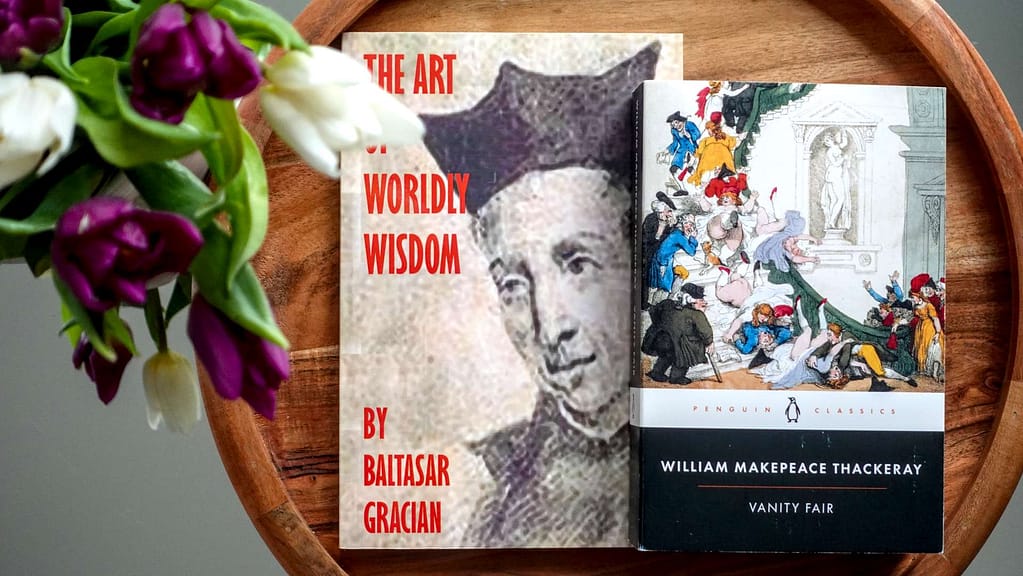

The Ethics of Manners: Comparing Baltasar Gracián and Becky Sharp

If Carson’s rulebook represents the outward expression of manners, Baltasar Gracián’s The Art of Worldly Wisdom reveals their interior architecture. Written by a seventeenth-century Jesuit priest, this collection of aphorisms is often described as a guide to navigating courtly life. In reality, it is something far more enduring: a manual for moral discernment in an imperfect world.

Gracián is not concerned with forks or formalities. He writes instead about restraint, timing, emotional intelligence, discretion and humility. “Know how to take a hint.” “Never compete with someone who has nothing to lose.” “Cultivate those who can teach you.” These are not rules of politeness, but principles for living among others without unnecessary harm.

What struck me most while reading The Art of Worldly Wisdom was how insistently it turns inward. Etiquette, here, is not performance but formation. It asks us to govern our impulses, to recognise when silence is more generous than speech, to temper self-importance before it spills outward.

Which is why Vanity Fair makes such a devastating companion text. Thackeray opens his novel at Miss Pinkerton’s Academy for Young Ladies, an institution devoted to producing polished, marriageable women through careful surface refinement. Becky Sharp, its most brilliant graduate, has mastered every rule. She curtsies flawlessly. She charms effortlessly. She performs civility with virtuoso precision.

She is also, as the novel makes unmistakably clear, morally hollow.

Becky Sharp embodies the danger of etiquette without ethics. Her manners do not restrain her; they enable her. Politeness becomes camouflage. Charm becomes a tool of extraction rather than connection.

Here, Gracián and Thackeray meet in a silent agreement: true manners emerge from character, not memorisation. Without inner work, etiquette is not merely empty — it is actively dangerous. A person who knows all the right gestures but lacks genuine consideration is simply a more efficient manipulator.

Why Manners Matter Now

I am writing this in early 2026, in a world that seems perpetually on edge. We champion authenticity while treating it as permission to offload our moods, our noise, our needs onto everyone within reach. We’ve confused informality with equality, as though the absence of structure automatically produces fairness. We’ve decided that etiquette is elitist, that manners are a tool of oppression, that any form of self-restraint is somehow a betrayal of our true nature.

But what if we’ve misunderstood its function entirely?

What if good manners are not the enemy of freedom, but one of its foundations? Not the brittle, exclusionary codes of the past, but a shared framework that recognises a simple boundary: your freedom to occupy space ends where another person’s begins.

Taken together, the four books at the heart of this essay sketch the outline of a modern etiquette. One that is elevating rather than exclusionary, rooted in character rather than performance, flexible rather than rigid, and accessible to anyone willing to learn. Not a return to a mythical golden age, but a selective inheritance — preserving what allowed people to coexist with grace, while discarding what enforced unjust hierarchies.

We do not need to resurrect Edwardian England to acknowledge that something has been lost. We need a new etiquette for a new age: one that values consideration over volume, discernment over impulse, and care over constant assertion.

A Beginning, Not a Conclusion

In the weeks to come, I’ll be exploring etiquette guides from six cultural traditions, each offering its own vision of how to live well among others — and each revealing its own blind spots. But for now, these four books sit on my desk as a compass.

They remind me that excellence in conduct can be a form of dignity. That discipline without humanity becomes hollow. That manners without morals are a liability. And that true courtesy is never about polish alone, but about the inner work that makes living together possible.

The next time someone elbows past me in an airport queue or conducts a speakerphone conversation in a confined space, I’ll try to remember this: many of us were never taught any better. Somewhere along the way, we decided that manners were obsolete — a relic of unjust systems rather than a shared language of care.

Perhaps it’s time we reclaimed them. Not as instruments of exclusion, but as the quiet architecture of a freer, more humane public life.

As Gracián reminds us, “A person of good breeding is one who gives pleasure to everyone — and pleasure to himself.”

That, to me, still sounds like freedom.

The Reading List

For the Skeptic: Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Professional: The Downton Abbey Rules for Household Staff – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Stoic: The Art of Worldly Wisdom by Baltasar Gracián – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

For the Empathetic: The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro – 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

Note: This post contains affiliate links. If you choose to purchase through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thank you for supporting my work!

A short note on how and why I share book links

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.