Belgian Advent Calendar – Day 20

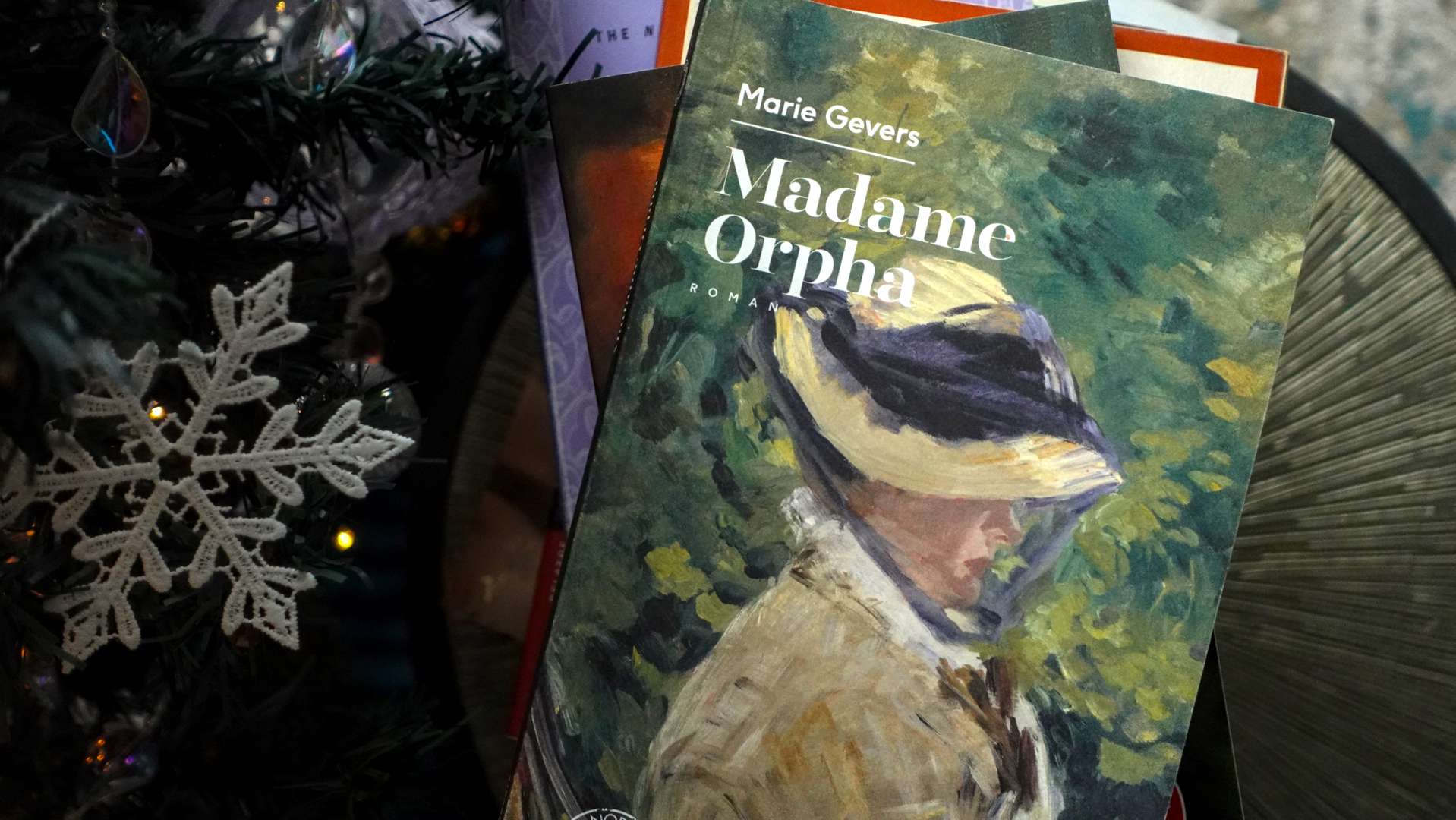

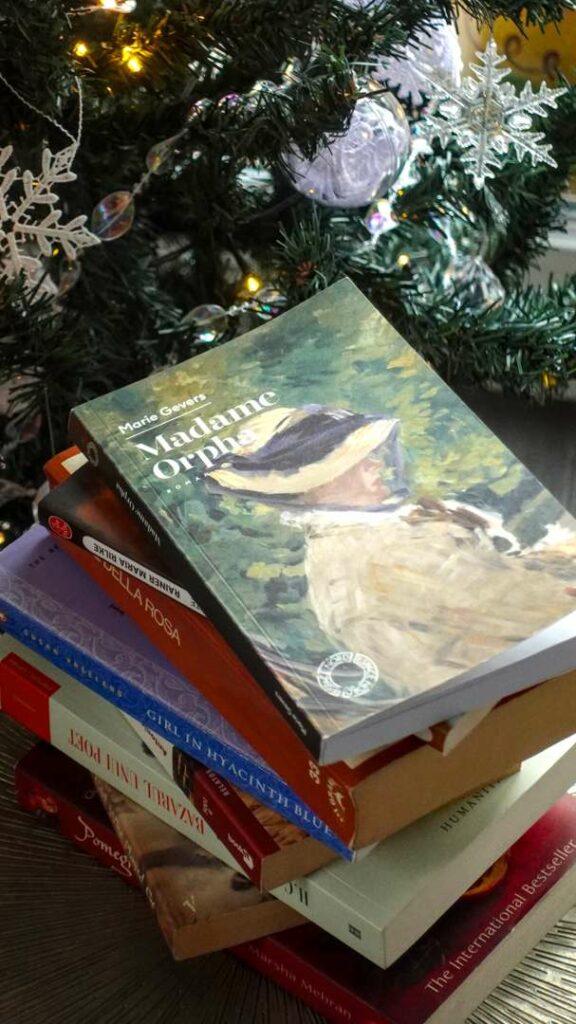

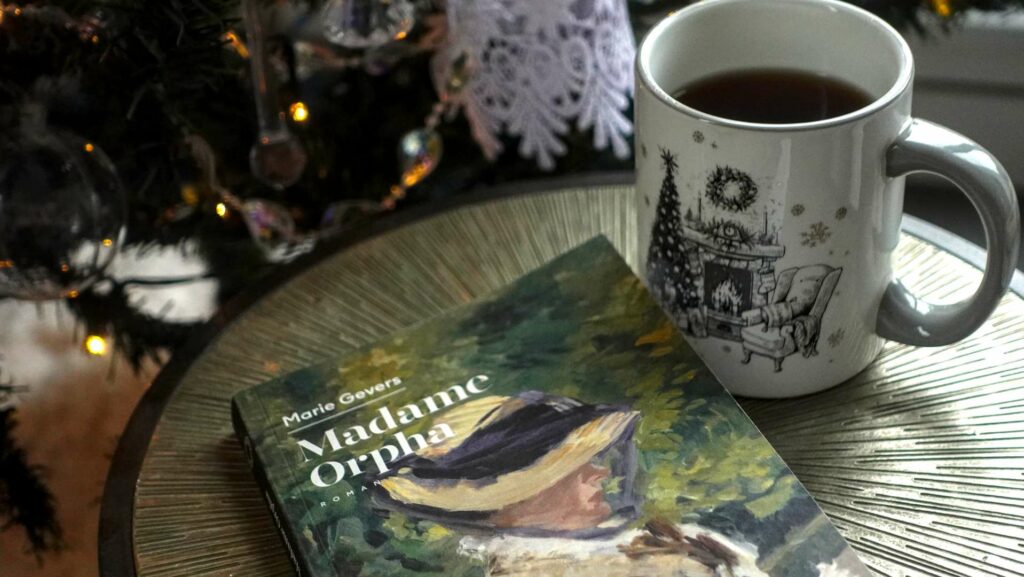

I’m sitting here with a cup of tea and a brand new copy of Madame Orpha ou la Sérénade de mai and I keep pausing to stare out the window at the grey December sky, thinking about something that puzzles me endlessly: how is it possible that authors who are considered absolute pillars of their country’s literature—writers who shaped the way an entire nation thinks about itself—never get translated into other languages?

Marie Gevers is one of those writers. The first woman ever elected to the Royal Academy of French Language and Literature in Belgium, a literary figure who captured something essential about Belgian life and landscape, and yet—nothing in English. Not a single novel. It’s baffling, really, and more than a little frustrating.

Because here’s what we lose when works remain locked in their original languages: we lose the chance to nurture not just our intellectual capacity, but our humanity itself. Reading literature from other cultures in translation—when we can’t access it in the original—is essential. It makes “the other,” “the stranger,” less strange. It bridges language barriers and distances. It reminds us that fundamentally, across all our different ways of speaking and living, we are all the same. And maybe, when we do disagree about something, we’re less inclined to let conflict turn into war. Why would we attack one another, when we know we’re all living as one ?

But I’m going to talk about Gevers’ work anyway, even knowing that most of you won’t be able to read it, because sometimes you need to know that something exists, that it’s out there waiting, even if you can’t access it yet. Maybe someone will hear this and decide it’s time to change that. Maybe that someone is you.

Madame Orpha or the May Serenade is an autobiographical novel of immense sensibility, a book that captures the beauty and charm of the Belgian countryside in a way that feels both specific and universal. It’s narrated through the eyes of a young girl spending her childhood in the Flemish countryside, observing the adults around her—particularly the enigmatic Madame Orpha, wife of the local tax collector, whose story becomes the village’s defining piece of gossip and, somehow, just another thing that happens in life.

Because here’s the heart of it: Madame Orpha fell in love with Louis, the gardener. A passion that defied all logic, all propriety, all common sense. The wife of a respectable official and a man who works the land. And the village—in that very Belgian way—is simultaneously scandalized and utterly unsurprised. They’re compassionate and judgmental in equal measure, talking about it in hushed tones that the child overhears, trying to understand what it all means.

What strikes me most is how the novel treats this scandal with a kind of steady humor, never excessive in any direction. It’s not a grand tragedy, nor is it played for cheap laughs. It’s just… one of those things that happens. People fall in love with the wrong person. Life gets complicated. The village talks about it. And somehow everyone keeps going, because what else would you do?

There’s something very Belgian in that temperament, isn’t there? That refusal to be overly dramatic about things, even when they are genuinely dramatic. That capacity to hold both judgment and compassion in the same breath, to acknowledge that yes, this is shocking, and also, well, these things happen.

What completely won me over was the child’s point of view in the storytelling. The way she observes the adults around her, trying to make sense of their behavior, piecing together meaning from fragments of conversations that don’t quite add up. She hears about Madame Orpha and Louis in bits and pieces—a comment here, a meaningful look there, conversations that stop when she enters the room. And from all these fragments, she constructs her understanding of what love is, what scandal means, what it looks like when adults fail to behave the way they’re supposed to.

But what fascinates me most as a linguist—what made me keep stopping to write down passages and make notes—is how the novel becomes an ode to the harmonious blend of Belgium’s two cultural poles. Marie Gevers spent her childhood in Flanders but was raised, like many well-off children of her time, entirely in French. She lived constantly between two languages, two ways of seeing and describing the world.

And here’s what she admits, what I find absolutely fascinating: she had a tendency to use French for analytical subjects and Flemish for emotional ones. Different languages for different modes of being.

As someone who juggles between languages constantly, who watches my own reflexes shift depending on which language I’m speaking, who observes the same patterns in the people around me—this resonated deeply. It’s not just about vocabulary or grammar. It’s about how language shapes thought, how the language you choose determines not just what you can say but how you feel while saying it.

Gevers writes about this linguistic duality not as a conflict but as a richness, a way of seeing the world in stereo rather than mono. The French gives her precision, structure, the ability to analyze and articulate. The Flemish gives her warmth, directness, access to emotions that somehow don’t translate into the other language.

I keep thinking about what we lose when writers like Marie Gevers remain untranslated. It’s not just that English readers miss out on a beautiful novel—though they absolutely do. It’s that we lose part of the conversation about what literature can be, about the different ways different cultures understand childhood, memory, landscape, language itself. About how a village in Flanders processes scandal. About how a child learns what love means.

So even if you can’t read Madame Orpha right now, know that it exists. Know that somewhere in the Belgian literary tradition there’s this gem of a novel that understands something essential about living between languages, about seeing the world through a child’s eyes, about the quiet beauty of paying attention, about how love refuses to obey the rules we set for it.

And maybe, just maybe, one day someone will decide it’s time for the rest of the world to meet Madame Orpha and her gardener too.

See you tomorrow for another Belgian discovery.

Until then, Merry Advent!

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.