When Reading Becomes Revolution

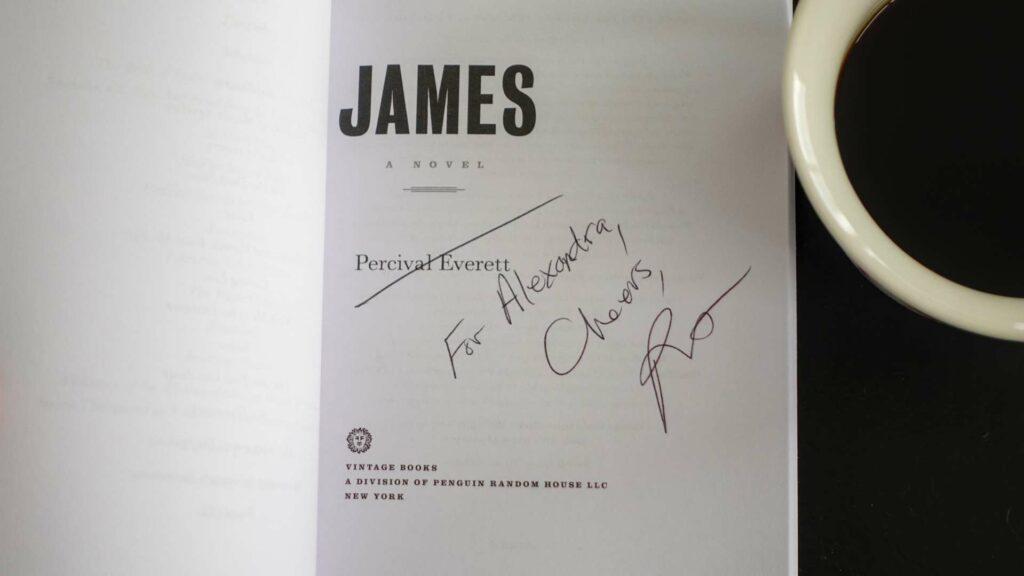

I never thought of myself as subversive until Percival Everett told me I was.

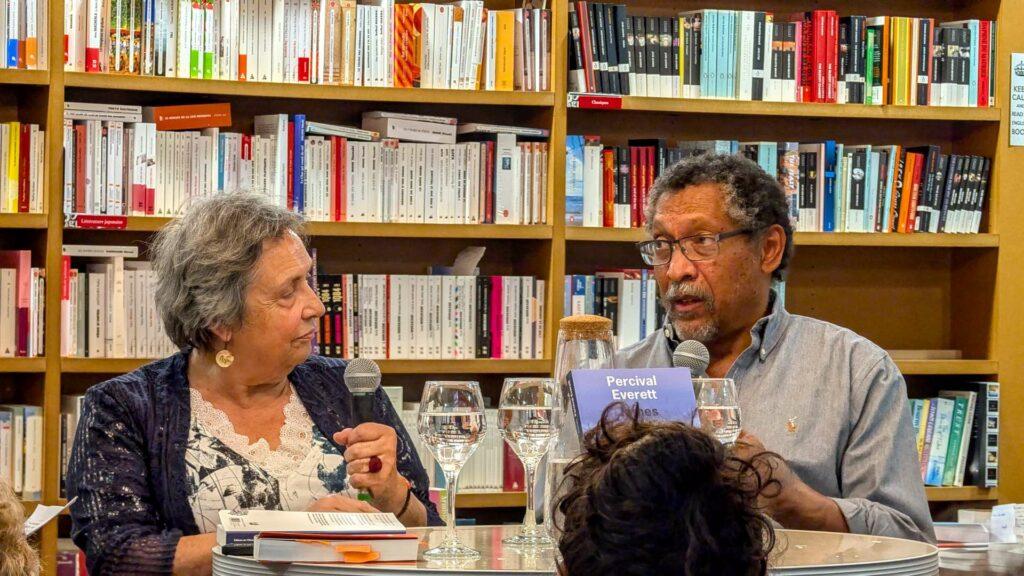

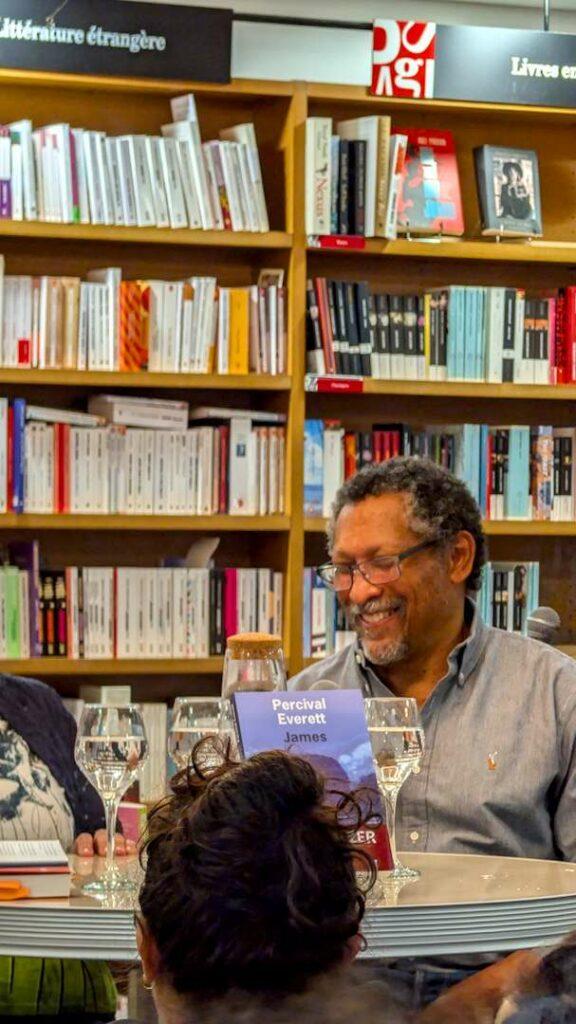

It happened on a September evening at the Librairie Millepages, tucked away in a small courtyard in Vincennes like a secret shared among book lovers. The space itself feels conspiratorial—two floors of carefully curated titles winding through narrow passages, the kind of bookshop where librarians edit seasonal newspapers and create displays that feel less like marketing and more like invitations to fall down rabbit holes of discovery.

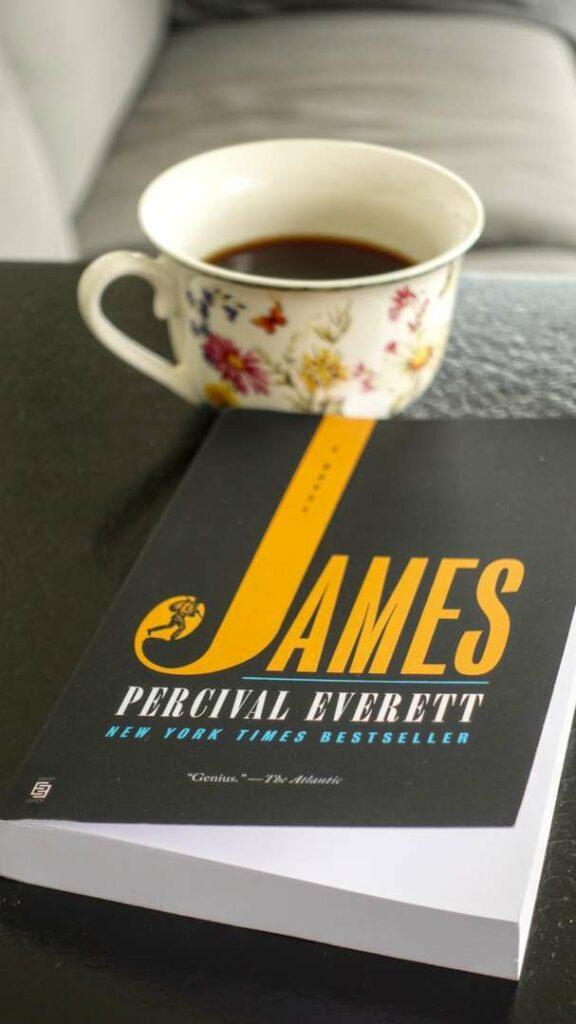

That night, the intimate room was filled with readers who had come to hear Everett discuss his novel James, the retelling of Huckleberry Finn from Jim’s perspective that has captivated literary circles this past year. I had listened to the audiobook in preparation, Dominic Hoffman’s extraordinary narration turning my daily walks into theater, each chapter an intense one-man performance that left me breathless.

But it was Everett’s live voice that stopped me cold.

“The most subversive thing we can do in any culture,” he said, “is to read.”

The second most subversive thing, he continued, was to found a book club. The third, to write.

I felt something shift. For years, I’ve been building The Ritual of Reading as what I thought was a gentle space—a place for quiet reflection, for savoring books like delicacies, for finding beauty in the slow rhythms of literary life. I called it a ritual because it felt sacred, not because it felt radical.

But sitting in that bookshop, surrounded by other people who had chosen to spend their Friday evening talking about literature, I began to understand what Everett meant.

The Language Beneath the Language

What had moved me most about James was Everett’s treatment of language itself. In the novel, Jim is not the simple, dialect-speaking figure from Twain’s original, but a man who has taught himself to read and write with extraordinary skill—yet who must hide his intelligence behind the very dialect that white society expects from him.

“Oppressed people find ways to speak to each other that don’t allow entry to their enemy,” Everett had explained.

This linguistic masquerade haunted me. Jim becomes a master performer, code-switching not just between vocabularies but between entire identities, revealing his true self only in safe spaces, with trusted companions. The tragedy is not that he lacks intelligence, but that he must constantly diminish himself to survive.

As someone who navigates language daily—living in French, thinking most often in three languages simultaneously, writing in English for readers across cultures—I recognized something profound in Jim’s performance. How often do we all modify our voices depending on who’s listening? How often do we dial down our complexity to avoid making others uncomfortable?

In our current moment, I see this everywhere. Thoughtful people softening their observations, intellectuals apologizing for their curiosity, readers almost embarrassed by their depth. It’s as if nuance itself has become suspect, as if the very act of thinking carefully has become a kind of transgression.

The Radical Act of Attention

This is what Everett meant, I think, when he called reading subversive. In a world that rewards quick takes and surface impressions, the simple act of sustained attention becomes revolutionary. To sit with a book for hours, to let another consciousness inhabit your mind, to emerge changed by the encounter—this is not passive consumption. This is active resistance to a culture of distraction.

The rentrée littéraire, this annual September celebration when France floods its bookshops with hundreds of new titles, suddenly felt different through this lens. What I had always seen as a fashion phenomenon with great marketing now appeared as something more urgent: a society collectively insisting that literature matters, that complex ideas deserve time and space, that the inner life is worth celebrating.

At Millepages that evening, surrounded by people who had chosen books over screens, conversation over consumption, I understood that we were all participating in something quietly radical. Not because we were protesting anything, but because we were practicing attention. We were insisting on depth.

The Power of the Few

When someone asked Everett about the future of literature in our digital age, his response was illuminating:

“I live in a country of 350 million people, and if I write a novel that sells 50,000 copies, my publisher will be ecstatic. But if I’m a musician and I have an album that sells 50,000 copies, I’m considered a failure. This is the world we live in. But then I remember Picasso’s Guernica—a painting that has changed the face of the world through the force of its message, and yet it has been seen by less than 5% of the population of the planet. So I believe that art is powerful simply because it exists, not because of its relative success measured by a subjective society.”

This struck me like lightning. For months, I had worried about reach, about growing readership, about making The Ritual of Reading “successful” in measurable terms. But Everett was suggesting something different entirely: that ideas spread through quality of impact, not quantity of exposure. That a single reader deeply moved might matter more than a thousand casually engaged.

Walking home through the quiet streets of Vincennes that night, I thought about Guernica—how it continues to speak against war decades after Picasso painted it, how its power comes not from being seen by everyone but from being truly seen by those who encounter it. How it changes individuals who then change the world around them, one conversation at a time.

The Revolution Continues

I left that evening with a new understanding of what I’m creating here. The Ritual of Reading is not just about celebrating books—it’s about preserving space for the kind of thinking that books make possible. In a world increasingly hostile to complexity, every quiet corner where someone sits with a novel becomes a small act of rebellion. Every book club becomes a resistance cell. Every thoughtful conversation becomes a revolutionary act.

This is why I continue to shape this space as somewhere books are not just consumed but lived with, reflected upon, celebrated as companions in our daily rituals. Not because it’s peaceful—though it is—but because it’s essential. Because someone needs to keep the fires burning for sustained thought, for careful attention, for the radical belief that inner life matters.

Reading, I now understand, is not escape from the world. It’s preparation for making it better.

Until next time, enjoy the freedom to read !

P.S. If this reflection resonated with you, you might enjoy the quiet conversations I share each month in my Ritual of Reading newsletter. It’s a space where I write as I would to a friend, weaving together books, seasons, and the small rituals that give rhythm to our days. Consider this an open invitation to join our small revolution, one reader at a time (click here to subscribe).

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.