Medieval Advent Calendar Day 12

Merry Advent, dear friends! Welcome back to our twelfth day of medieval adventures, where today we encounter one of the most surprising and multifaceted women to have lived during the High Middle Ages—a figure whose genius spanned so many disciplines that she seems almost impossibly ahead of her time.

I return once again to Régine Pernoud for my historical research, though English-speaking readers will find many excellent biographies of today’s protagonist available to them.

Hildegard of Bingen was a German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, medical writer, and practitioner—a list of accomplishments that would be remarkable in any era, let alone the twelfth century. Born in 1098 into a family of lower nobility, the youngest of seven siblings, Hildegard was a sickly child who experienced mystical visions from the age of three. Her family entrusted her to the church very early, a common practice for children who seemed marked by the divine or unsuited to worldly life.

The religious community naturally tends to focus on her spiritual work—both as an abbess who led her convent with remarkable independence and as a philosopher-theologian who interpreted her visions as messages sent directly from God. Within its historical context, this aspect of her life certainly merits attention. Yet it wasn’t what drew me to her initially.

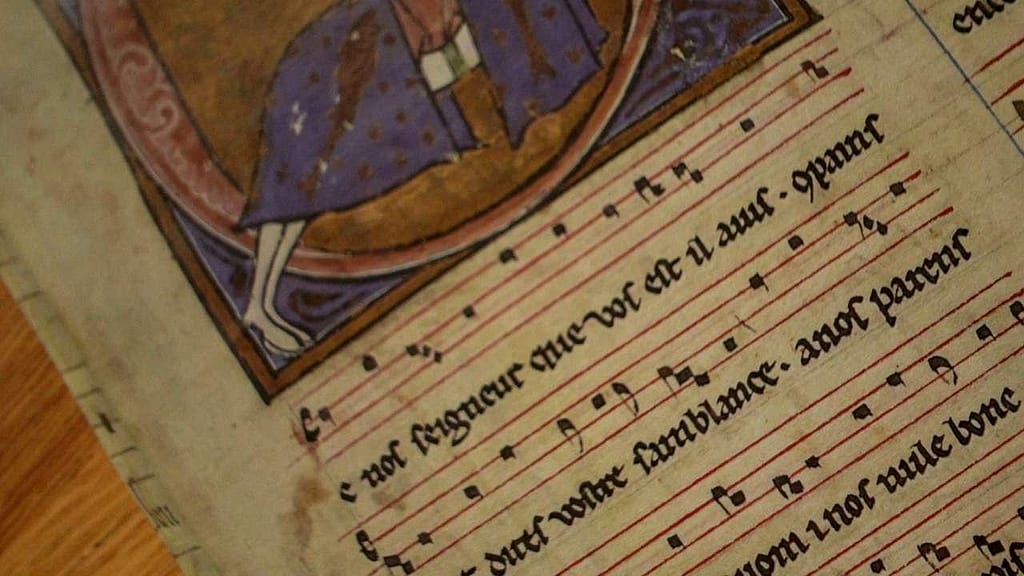

What captivated me first was Hildegard’s music. She stands among the most important medieval composers and is the earliest known woman composer in the Western classical tradition, an important exponent of sacred music during the High Middle Ages. Seventy musical compositions survive, each paired with its own original poetic text—one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers of any gender. Hildegard believed profoundly that music possessed powerful, even medical effects on people, and she employed it as a form of biblical meditation. The effects were noticeable to her contemporaries, though it’s only with modern neuroscience that we’re beginning to understand the brain’s mechanisms when exposed to her compositions.

This practice—using sound as therapy—appears in most of the world’s religious traditions. For centuries it remained confined to the sphere of the mystical, available only to worshipers and understood solely through spiritual frameworks. Only recently has science begun studying these phenomena independently, liberating sound therapies from exclusively religious contexts. I find Hildegard’s approach to sound absolutely fascinating, and centuries ahead of her time in its intuitive grasp of something we’re only now beginning to measure and understand.

There was another field in which she excelled and for which she represented so much: medical knowledge and natural remedies. Today we think of alternative medicine as predating the scientific breakthroughs of modern times. Well, this was precisely that era—yet Hildegard’s work represents the beginning of something more systematic. During the High Middle Ages, knowledge of the body and therapies for its ailments were becoming increasingly documented. Hildegard catalogued her understanding in two major works: Physica, composed of nine books describing the scientific and medicinal properties of plants, stones, and animals; and Causae et Curae, an exploration of the human body, its connections to the natural world, and the causes and cures of various diseases.

Although she inherited certain notions and theories from ancient medicine, Hildegard developed her own concepts through a unique method combining careful observation, logical deduction, and what she experienced as divine inspiration. Her books hold particular historical significance because they document areas of medieval medicine that were otherwise poorly recorded, since their practitioners—predominantly women—rarely wrote in Latin or had access to formal education that would preserve their knowledge.

Whenever I prepare herbal tea, I think of Hildegard’s legacy. Before me sits a blend called Jardin des Simples—named for the medicinal herb gardens maintained by monasteries throughout the Middle Ages—with calming properties gathered from raspberry and mulberry leaves, rosemary, lemon balm, fennel seeds, sage, olive leaves, and lavender flowers. In a world offering so many high-tech options for treating nearly everything, it would be absurd to rely solely on herbalism. Yet preventative medicine works hand in hand with modern science, making Hildegard once again a visionary in every sense of the word.

For French-speaking readers, I recommend a short novel written in a most unusual voice, directly inspired by Hildegard’s life: La Clôture des merveilles by Lorette Nobécourt. More than a biographical narrative, this reads as a manifesto for radical insubordination that translates into complete freedom. It unfolds almost like a prose poem—delicate yet strong, the sort of book you remember less by its plot than by the feeling it leaves behind.

And before I close for today, I must mention that Hildegard’s correspondence, preserved in precious archives, includes two letters exchanged between herself and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Were you surprised? I confess I wasn’t—of course these two extraordinary women knew each other. Of course they wrote to one another. How could they not?

Until tomorrow, dear friends—may your Advent be filled with music, wisdom, and the healing properties of simple things.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.