Austrian Advent Calendar Day 23

Hello, dear friends, and welcome to the final book review of our Austrian Advent Calendar.

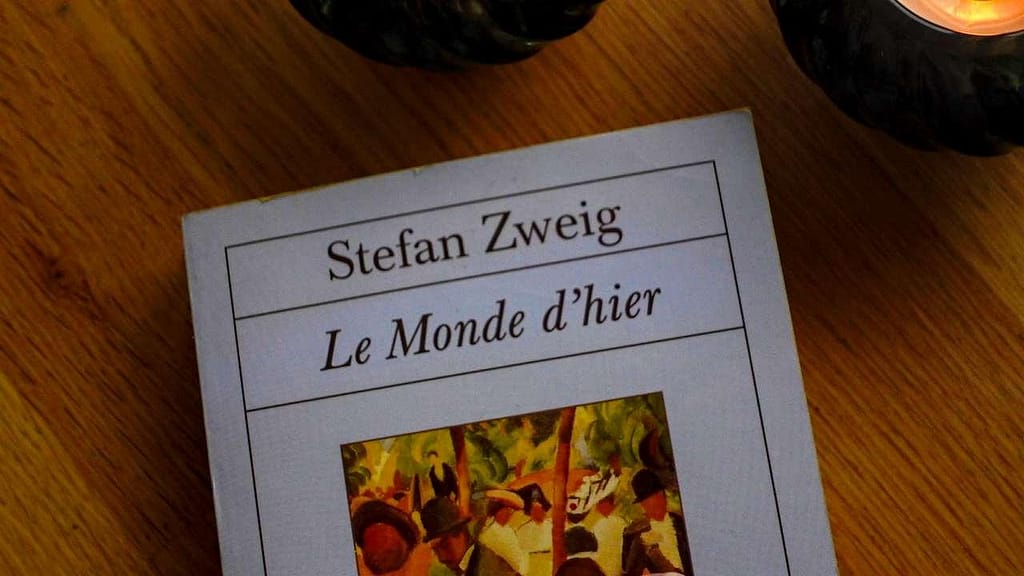

For the past twenty-two days, I’ve shared with you novels and histories, essays and art books—pieces that have composed a deeply personal portrait of Austrian culture. I could not have imagined a more fitting finale for this marathon of reading than Stefan Zweig’s memoir, The World of Yesterday.

Considered by many the most eloquent testament to the Habsburg Empire’s final flowering, The World of Yesterday carries the apt subtitle Memoirs of a European. Zweig situates Austrian life firmly at the heart of European culture, acknowledging both its unique characteristics and its undeniable connections with the rest of the continent. This wasn’t merely an Austrian world he mourned—it was a European one, cosmopolitan and interconnected in ways that would become unimaginable within a single generation.

I would say that reading about life in “the olden days” enchanted me, but you might think me conservative or overly nostalgic. Let me reframe it this way: Zweig’s attachment to the values and passions that animated people at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century is something I recognize in myself. Young students eager to read their contemporaries rather than limiting themselves to mandatory classics. Theatergoers so engaged with performances that their debates became more fierce than professional critics’ reviews. These weren’t merely exceptional individuals—they represented a broader cultural norm.

A short note on how and why I share book links

We spoke just two days ago about the rise of the middle class in Viennese culture during the nineteenth century. The World of Yesterday shows us the result: a society where cultivation wasn’t reserved for aristocrats and thus wasn’t perceived as snobbish or exclusionary. Being interested in art and ideas, maintaining a circle of friends who shared those passions, was something nearly everyone aspired to. Education and cultural literacy were seen not as markers of class superiority but as essential components of a life well lived. Reading about that world brings me genuine pleasure—not because I romanticize the past wholesale, but because it demonstrates what becomes possible when culture is democratized rather than gatekept.

You do feel throughout the memoir that this trail of memories is punctuated by profound regret for what the world had become by the early 1940s when Zweig wrote it. This is only understandable: Hitler’s rise to power pushed him into exile, nationalism metastasized across Europe, and all the values he held most dear—cosmopolitanism, tolerance, intellectual freedom—were being systematically destroyed. He would take his own life in Brazilian exile in 1942, unable to bear witness to what Europe had become.

Yet the book’s melancholy didn’t bring me down. I didn’t experience it as a “here’s what’s wrong with the world” lament, but rather as a “look what the alternative could be” invitation. Zweig wasn’t simply mourning—he was preserving, documenting a way of life so that future generations might know what had been possible and might, perhaps, build something like it again.

This perspective stayed with me while wandering the streets of Vienna. Many Europeans today perceive Austria as a somewhat closed society, perhaps overly obsessed with preserving the lifestyle of bygone days. I cannot speak to what it’s like to live there permanently, but as a visitor, I felt welcomed. I sensed genuine joy in how Austrians share their most precious symbols and traditions—many of them connected to an Empire that, for all its imperfections and eventual collapse, elevated a country and its people in ways still visible today.

Zweig captures this spirit perfectly: “‘Live and let live’ was the famous Viennese motto, which today still seems to me to be more humane than all the categorical imperatives, and it maintained itself throughout all classes.”

Leben und leben lassen—live and let live. What a revolutionary concept, really, and how rare. Not tolerance as grudging acceptance, but active permission for others to flourish in their own way. This was the heart of what Zweig mourned: not merely the cafés and the opera and the elegant Ringstrasse, but the fundamental decency of a society that valued cultivation over aggression, conversation over confrontation, cosmopolitanism over tribalism.

The World of Yesterday is elegiac without being hopeless. It’s a love letter to a vanished world, yes, but also a blueprint for what we might build again if we choose to value the things Zweig valued: education, art, tolerance, beauty, and the belief that these things should belong to everyone, not merely the privileged few.

Until tomorrow, dear friends, for our final Austrian stroll of the season—may we carry forward the best of what yesterday offered and leave behind what needed to end.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.