There is a point during a visit to the Keukenhof Gardens when beauty stops being a visual experience and becomes something closer to physical overwhelm. For me, it arrived thirty minutes in, standing before a bed of parrot tulips—their petals fringed and feathered in shades of burgundy and cream—when I found myself asking a question that had no rational answer: how is any of this even possible?

Six petals forming a cup atop a single stem rising from a bulb buried in Dutch soil. The geometry is simple. The effect is not.

I had waited ten years for this moment. A decade of photographs scrolled past on screens, documentaries watched, travel guides bookmarked. I thought I knew what to expect. I was wrong. No image can prepare you for the sensation of standing among seven million flowering bulbs, 32 hectares of orchestrated colour, 26,000 daily visitors moving through the rain-soaked paths of the world’s largest floral park. And somehow, impossibly, never feeling crowded.

The tears came later. Not from sadness, but from something closer to gratitude—or perhaps simple capitulation to beauty that asks nothing of you except that you witness it.

A Teenage Memory, A Delayed Dream

My fascination with tulips began long before Keukenhof entered my imagination. As a teenager, I watched my mother descend into what can only be described as a tulip frenzy in our garden. She ordered nearly twenty varieties from Dutch nurseries, each one exceptional, each one a different proclamation against the dullness of winter. The bulbs arrived in autumn, anonymous and unpromising. By spring, our garden had become a small theatre of colour.

I think that was the first time I considered visiting the Dutch tulip fields—not as a vague someday possibility, but as a specific longing. Years later, a dear friend sent me photographs from Keukenhof, and the longing crystallized into intention. It took another decade for the dream to materialize, but when it did, I prepared for it the way I prepare for most meaningful experiences: with a book.

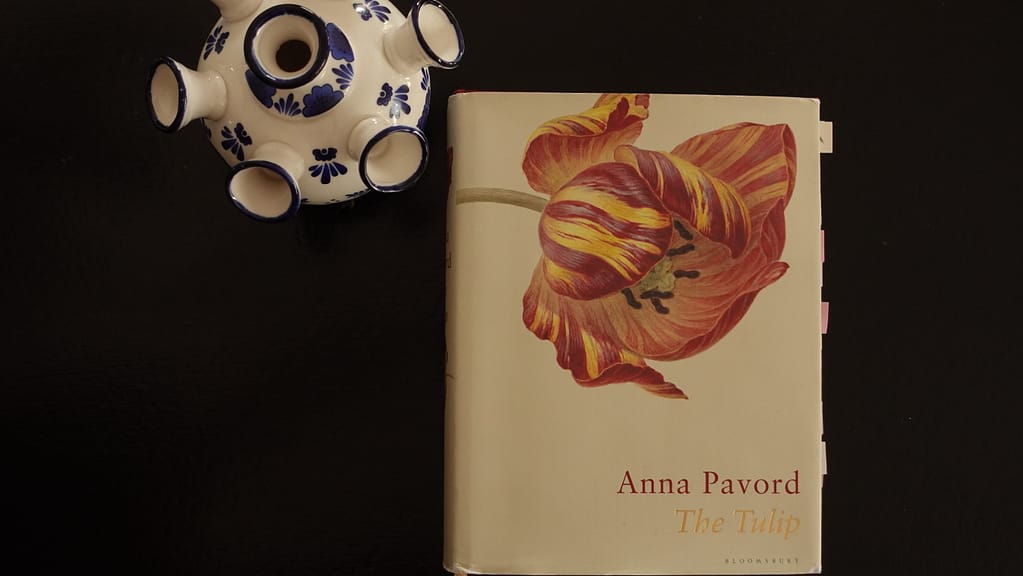

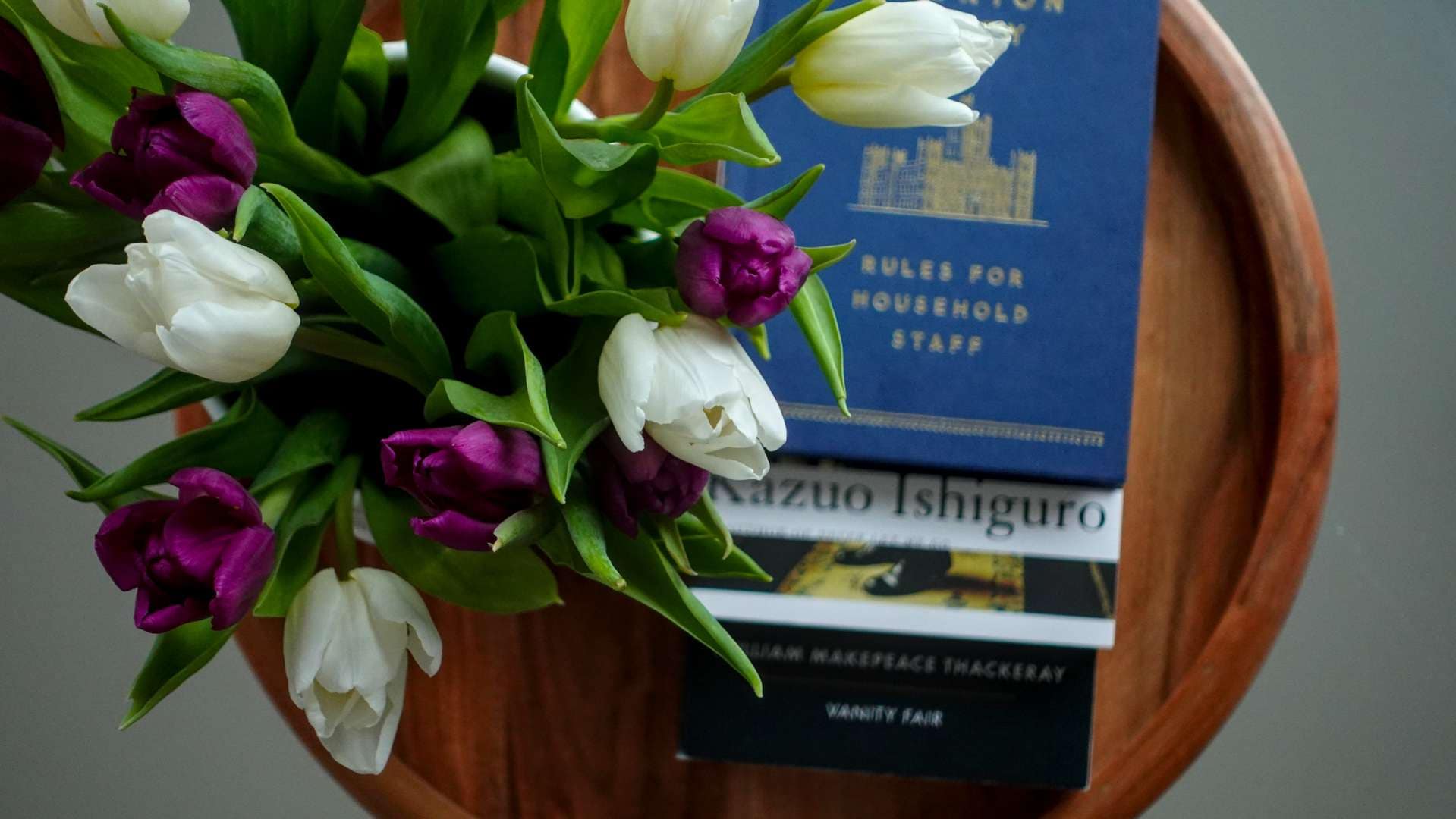

If tulips are your passion, Anna Pavord’s The Tulip is what your personal library needs.

An Encyclopedia of Desire

Pavord’s book is first a visual feast—botanical illustrations, centuries-old paintings, Ottoman manuscripts—and then a historical odyssey. From the flower’s origins in the mountain ranges of Central Asia to its arrival at the Ottoman court, from the Dutch Tulipomania of the 1630s to the English florist societies of the Victorian era, this is the biography of a flower that has inspired both art and economic collapse.

I am not usually a patient reader. I prefer narrative momentum to encyclopedic thoroughness. But Pavord’s work, like most deeply researched publications, imposes a rhythm of its own. I began reading before my trip and finished two months afterward. It became the kind of book you return to repeatedly, searching for a specific detail or a half-remembered anecdote, and it never disappoints.

The tulip, I learned, was not always called a tulip. In Turkish and Persian, the flower is lale—a word with its own poetry, its own history. The name we use in English comes from a diplomatic mistranslation. During an official state visit to the Ottoman court, a European visitor admired the flower tucked into a dignitary’s turban. When he asked what it was called, his interpreter misunderstood the question and answered “tülbent”—the Turkish word for turban. The error stuck. We have been calling it the wrong name ever since.

At the height of Ottoman power, tulips were not merely decorative. They were political currency, aesthetic philosophy, spiritual metaphor. Sultan Ibrahim’s florist-in-chief, Sari Abdullah Efendi, presided over gardens where tulip parties were staged with the seriousness of state ceremonies. Guests reclined on silk cushions beneath hanging lanterns, surrounded by vases of carefully selected blooms. Canaries and nightingales were released among the flowers. The entire affair was designed to overwhelm the senses, to create an experience of beauty so total it approached the divine.

Europe inherited this obsession but transformed it into something more mercantile. The first tulipomania, Pavord reveals, took place in France before the Dutch made it infamous. But it was in the Netherlands—with its keen sense of commerce, its sophisticated trading networks, its willingness to gamble on the irrational—that the tulip became the center of history’s most notorious speculative bubble. At the peak of the mania in 1637, a single bulb of the Semper Augustus variety sold for more than the price of a canal house in Amsterdam.

The madness passed. The flower remained.

Keukenhof: Where History Blooms

The Keukenhof Gardens occupy land that has known cultivation for centuries. In the 15th century, a castle stood here, surrounded by kitchen gardens—keukenhof in Dutch, the herb garden where ingredients were grown for the castle’s table. The current incarnation dates to 1949, when a consortium of Dutch bulb growers and nurseries transformed the grounds into a living showcase for the spring flower industry.

Every year, the cycle repeats. From October to December, seven million bulbs are planted according to designs conceived a year in advance. From mid-March to early May, the gardens open to the public. Eighty acres of crocus, hyacinth, daffodil and above all, tulip, arranged in beds and borders, scattered beneath trees, massed along waterways.

I visited on a rainy day in April. The clouds hung low and grey, the kind of weather that sends sensible people indoors. Yet the paths were full—umbrellas jostling, rain ponchos rustling, cameras held aloft to capture blooms jeweled with raindrops. Visitors of every age and origin moved through the gardens with the quiet concentration of pilgrims. This was not casual tourism. This was something closer to devotion.

Once I reached maximum colour saturation—a point I had not known existed until I experienced it—my attention shifted briefly to the people around me. Here were strangers united by nothing except the willingness to stand in the rain and bear witness to flowers. Some photographed obsessively. Others simply looked. A few, like me, cried.

My Keukenhof visit was a revelation, and one of the greatest surprises of recent years. Having dreamt of this for the past ten years, you can imagine I saw every photo and video online, every documentary and website, I knew it was magnificent. But the feeling you get when you’re actually there, cannot begin to compare. When I say that the beauty is overwhelming, I mean that 30 minutes into the visit I was already wondering how all of it is even possible. And then you get to a point where the only reaction you can have are tears of joy.

Once I’ve reached maximum colour saturation, my attention switched briefly to the visitors. Here were all these people of every age and cultural background, with rain ponchos or umbrellas, taking their time in front of each flower bed, absorbing the infinite beauty.

The Geometry of Wonder

What is it about the tulip that provokes such intensity?

Rebecca Wells wrote that “flowers heal me; tulips make me happy,” and I understand the instinct. But it feels incomplete. Happiness is too small a word for what I felt at Keukenhof. The tulip does not comfort. It does not soothe. It announces itself with an elegance that borders on arrogance, a cheeky declaration that winter has ended and colour has returned to reclaim the world.

I am usually drawn to scented flowers—roses, freesia, jasmine—blooms that appeal to the olfactory nostalgia I carry everywhere. The tulip offers no fragrance. Its appeal is purely visual, purely formal. And yet it captivates in a way that perfumed flowers sometimes do not. Perhaps because its beauty feels less intimate, less personal. The tulip does not seduce. It simply exists, unapologetically, in full chromatic glory.

Pavord’s book gave me the history, the context, the names and dates that anchor understanding. But standing in the rain at Keukenhof, surrounded by beds of blooms in shades I had no language for, I realized that knowledge only deepens mystery. Knowing how the tulip traveled from Ottoman gardens to Dutch fields, knowing the botanical mechanics of its bloom, knowing the economic forces that turned it into a commodity—none of this explains the sensation of standing before it and feeling your breath catch.

Six petals. A cup. A stem. A bulb.

It should be simple. It is not.

A Memory That Lasts

Even if I never return to Keukenhof—and I suspect I will, though perhaps not for another decade—the memory will remain. Not as nostalgia, but as proof that beauty, when encountered at the right scale and in the right spirit, can undo you completely.

The poet Fathima Shamla wrote that “love tastes like tulips having rain tea in a colored cup,” and on that grey April afternoon, standing among millions of flowers while rain drummed against my umbrella, I understood exactly what she meant.

Some experiences cannot be photographed, cannot be fully described, cannot be translated into language adequate to their magnitude. Keukenhof is one of them. You simply have to go. Preferably with Anna Pavord’s book read or half-read, preferably in the rain, preferably with an open heart and a willingness to be astonished.

The tulip, after all, has been astonishing us for centuries. It shows no sign of stopping now.

The Reading

The Tulip by Anna Pavord — 🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A comprehensive, beautifully illustrated history of the flower that captivated empires and inspired economic madness. Essential reading for anyone who has ever paused before a tulip bed and wondered how something so simple could be so sublime.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.