Scandinavian Advent Calendar Day 10

Iceland—what images does that word summon for you? For me, it conjures wild horses moving across volcanic plains, carpets of luminous moss softening ancient lava fields, waterfalls cascading over black basalt cliffs, geothermal springs sending steam into frigid air. But recently, I’ve added another dimension to this mental landscape: Iceland’s quietly extraordinary literature, which possesses a wildness all its own.

I must confess at the outset that I won’t attempt to pronounce this author’s name—she is far too talented and gracious for me to mangle the beautiful complexity of Icelandic phonetics. But Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir holds a particular place in my reading life, for hers was the first Icelandic novel I ever encountered, the book that opened that remote island’s literature to me.

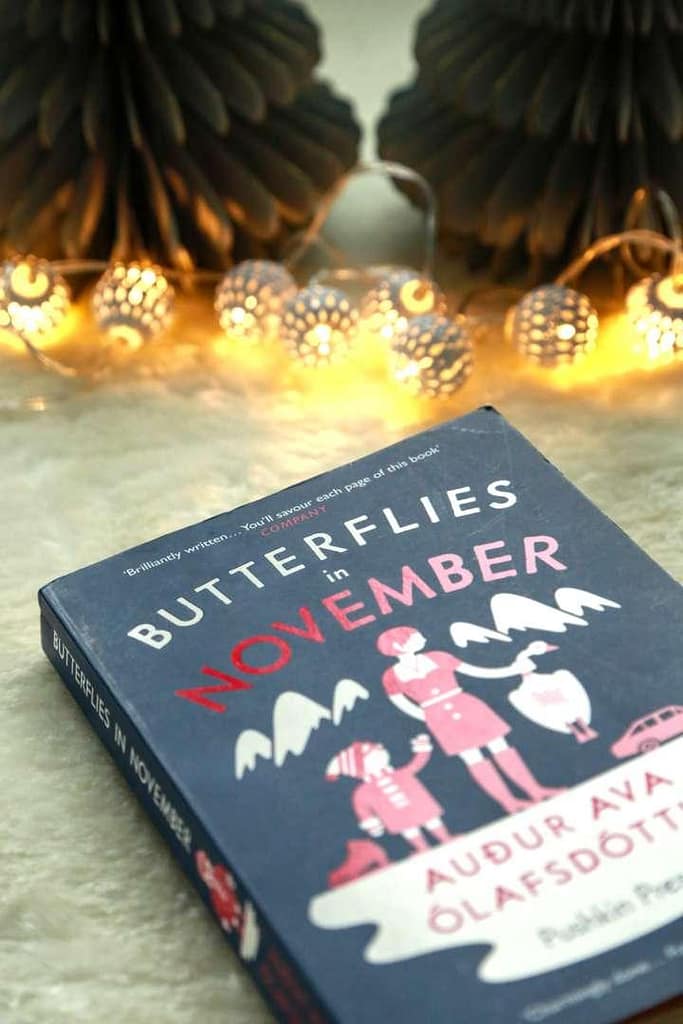

Butterflies in November follows an unlikely road trip across Iceland undertaken by two unexpected companions: a young woman whose husband has just left her, and a deaf four-year-old boy. The circumstances that bring them together matter less than what unfolds between them—a journey not merely across terrain but toward self-discovery, toward the kind of trust and companionship that emerges only through genuine friendship, unforced and unhurried.

What struck me immediately was the story’s apparent simplicity. They climb into a car, buy a lottery ticket, and begin driving. The prose, at least in Brian FitzGibbon’s English translation, feels deliberately unadorned—functional, even spare. There are no pyrotechnic displays of language, no baroque metaphors. The narrative transmits itself clearly, almost plainly. And yet something moved in me as I read. The plot doesn’t rely on dramatic reversals or heightened emotion, the language doesn’t call attention to itself, and still I found myself deeply attached to these characters. I wanted them to win that lottery. I wanted their journey to continue. I felt as though I occupied the back seat of that car, watching Iceland’s strange landscapes roll past.

🇺🇸 World of Books | 🇬🇧 World of Books | 🇫🇷 Momox Shop

A short note on how and why I share book links

This first encounter with Icelandic fiction gave me the sensation of wilderness itself—as though beneath an apparently simple surface lay deeper strata of meaning, not hidden but simply existing at a different frequency. We know that appearances deceive, but what happens when they seem deliberately undemonstrative, almost closed to interpretation? How does one perceive the subtler resonances the human ear wasn’t trained to catch?

My conclusion, eventually, was that the very search for “something more” represented a kind of conditioning I needed to release. I allowed myself simply to feel what the novel evoked without excavating for hidden symbolism or profound themes. The meaning was the feeling—that return to something wilder and less intellectualized in myself. From this small island at the edge of the Arctic came an unexpectedly generous reading experience, one that taught me as much about how I read as about what I was reading.

The linguist in me cannot resist sharing this perfectly crystalline observation from the novel:

“No words can be categorical enough to exclude any possibility of misinterpretation.”

There, in a single sentence, lies both the frustration and the beauty of language itself—and perhaps why Ólafsdóttir’s spare prose feels so honest.

Until tomorrow, dear friends—may you discover the wilderness that lives inside yourself.

Written by Alexandra Poppy

Writer, reader & curator of The Ritual of Reading

I’m Alexandra, the voice behind The Ritual of Reading. Somewhere between a stack of novels and a half-finished pot of tea, I keep finding traces of the life I want to live—slower, richer, filled with stories. The Ritual of Reading is where I gather what I love: books that linger, places with a past, and rituals that make ordinary days feel a little more meaningful. I write from Paris, where elegant bookshops and old-fashioned cafés offer endless inspiration—and I share it here, hoping it brings a spark to your own days, too.